The European financial crisis may have disappeared from the front pages of American newspapers, but the Continent’s economic challenges remain worrisome.

Most fundamentally, Europe is mired in a slow-growth rut with little sign of either sensible policy initiatives or the energy to implement them.

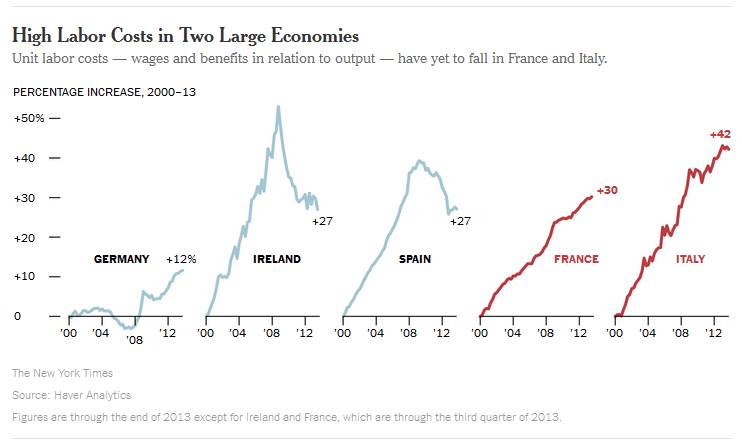

Ironically, countries like Spain and Ireland that precipitated the crisis have made the most progress, albeit painfully. Wrenching recession, some labor market reforms and widespread unemployment have pushed wages down, allowing these countries to regain a competitive position in world markets. But two of the largest countries that sit squarely at the heart of Europe — France and Italy — have dauntingly long economic “to do” lists.

For all practical purposes, Italy’s economic health hasn’t improved a whit since the euro crisis hit. Unemployment rose to a record high of 12.9 percent in January. Its economy is smaller than before the 2008 recession and expands only fitfully. Instead of improving its labor productivity, it’s creating an ever larger public sector debt burden. None of that should be surprising, as the country has continued to lurch from prime minister to prime minister, with a 39-year-old local politician, Matteo Renzi, now in charge. His 100-day plan is bold, but in Italy, change historically occurs, if ever, in years or decades.

France’s president, François Hollande, succeeded in achieving change — but initially in utterly the wrong direction. Hefty tax increases terrified business and the wealthy French, a few of whom decamped to more hospitable tax climes. Foreign direct investment in France plunged 77 percent in 2012.

Amid the furor, Mr. Hollande tried to tack toward the center, but the course correction has so far seemed more theoretical than real. For example, the French government recently skirted European Union regulations, injecting more capital into Peugeot only on the condition that the struggling automaker not close plants or eliminate jobs. That’s exactly the opposite of how we brought the American auto industry back to health. In a global world, a manufacturer must be cost-competitive.

Nor is Peugeot a unique example. On a recent swing through Europe, I heard a similar story from an investment manager trying to restructure a company, as Peugeot was trying to restructure its operations. The manager was also met with a demand from the government that jobs not be cut.

Now Mr. Hollande is pledging to roll back oppressive tax increases, cut government spending and ease suffocating regulations. Little of that has yet happened, and Mr. Hollande suffers with a record-low approval rating.

The contrast with France’s archrival, Germany, which is expected to grow at nearly 2 percent in 2014, about double the rate in France, could not be more striking. Germany has done well at making itself competitive, although it’s not perfect. I met with German businessmen who complained that Germany had strayed from rational policy making in the critical area of energy. Two misguided decisions — to try to make the renewable energy business grow faster than makes economic sense and to accelerate the closing of its nuclear facilities following the Fukushima disaster — have left Germany with unnecessarily high energy costs and more pollution from burning dirty coal. German businessmen gaze wistfully at the United States with its free-flowing and cheap natural gas.

All told, to a visiting American investor trying to assess Europe’s prospects, most of the Continent just doesn’t feel as if it’s on the economic move. What ails its economies is a lack of what keeps the United States — for all of our problems — so high on the world’s leader board: flexible labor markets, the culture of innovation, immigration and a relatively light regulatory touch.

Meanwhile, of the 34 members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the 10 with the highest tax rates on earned income are in Europe. A promised Europe-wide banking supervision plan inches forward. More thorough fiscal integration remains a dream.

Implementing the necessary structural reforms is a messy, slow, politically contentious step-by-step process, perversely made more difficult by unperturbed capital markets.

Thanks to Mario Draghi’s dramatic statement in July 2012 that the European Central Bank would “do whatever it takes” to prevent a collapse of the euro, bond yields in countries like Italy have been hitting post-crisis lows, thereby removing the most extreme source of pressure for reforms.

Some see salvation in more aggressive moves by the E.C.B. Fine — avoiding deflation is a worthy goal. But recognize that the Federal Reserve’s bond-buying program reduced unemployment by only a smidgen. Europe still must face the need for more fundamental change and not be distracted by those who see a central bank’s printing press as a painless way out.