Originally appeared in the New York Times.

Yes, of course, we need a Green New Deal to address the world’s most urgent crisis, global warming.

Just, please, not the one that a flotilla of liberal politicians, including seven of the top Democratic presidential hopefuls currently in the Senate, are signing up for in droves, like children following the pied piper in the old legend.

Our modern-day pied piper, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, is trying to lure us into a set of policies that might help save the planet but at the cost of severely damaging the global economy.

To be sure, by the time the resolution was introduced into Congress, some of its most ludicrous provisions (like the deadline of 2030 for a full transition to renewable energy and the immediate halt to any investment in fossil fuels) had been eliminated or watered down.

But as important as continuing to prune the absurd or damaging provisions would be to add what is the most effective way to attack climate change: using taxes and market forces rather than government controls to reduce harmful emissions.

That has been a problem for decades, at least since Washington got seriously into the business of improving the environment, back in 1970 with the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency — under President Nixon!

Politicians prefer that approach because using regulation hides the costs of reducing emissions. The decision, for example, to force improvements in automobile mileage by requiring each manufacturer to improve overall fleet efficiency has added thousands of dollars to the cost of cars.

Higher car prices have the countervailing impact of encouraging Americans to hang onto their older, less fuel-efficient cars for a longer time, offsetting at least some of the gains from newer cars. Nor have the regulations, with their many escape hatches, kept consumers from buying even more sport utility vehicles and pickup trucks as gas prices have remained historically low.

Fortunately, there is a better way to address the climate problem at far lower cost to the economy: a tax on greenhouse gas emissions. That can be imposed in any number of ways. The 18.4 cent federal gasoline tax, for example, hasn’t been increased since 1993 even as most other developed countries impose far higher levies.

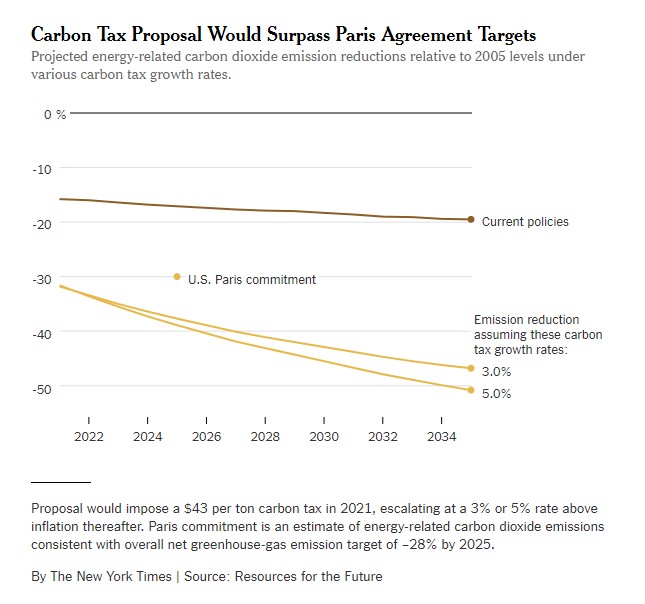

A particularly thoughtful proposal has come from the Climate Leadership Council, a bipartisan organization that counts more than 3,300 economists among its signatories. Elegant in its simplicity, the key provision would be the imposition of an escalating tax on carbon. At an initial rate of $43 per ton, the levy would be roughly equivalent to 38.2 cents per gallon of gasoline.

To prevent polluters from fleeing overseas, the tax would be imposed on imports from countries lacking a similar provision while exports to those countries would not be taxed. While difficult to implement, that component is important to work out.

The entire proceeds from the tax would be rebated to consumers. The council suggests an equal amount for each American; my view would be to exclude the wealthy (who hardly need the estimated $2,000 a year in payments) and disproportionately favor those closer to the bottom.

Why are so many economists, even conservative ones, in favor of a massive new tax? Because markets do not always price in “externalities” like pollution. In addition to cutting consumption, raising the price of carbon would arguably do more to encourage development of alternative power sources than all the massive new government spending programs that advocates of the Green New Deal envision.

Some technical problems would need to be addressed, such as how the higher prices would filter through inflation calculations and create unintended cost of living adjustments to wages and Social Security payments.

But those are details; the key point is that a carbon tax has been judged by climate hawks like Resources for the Future to be far more effective in reaching the goals of the Paris agreement than the well-intended regulations put in place by President Obama and his predecessors.

That’s at least part of why the plan enjoys support from an armada of organizations not often on the same page, like Exxon Mobil and Conservation International.

Historically, the politics of even small increases in the gasoline tax have been tough. A 2017 proposal in the House to increase tax by just one penny went nowhere. But recent polls suggest that perhaps sentiment is changing; a survey by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago found that 44 percent of Americans favor a carbon tax while only 29 percent oppose one.

Given how late we are to the climate battle, maintaining some sensible regulation will also be necessary. But a hefty carbon tax would go a long way toward winning the war.