The immigration problem Congress faces is large and complex. Let’s break it down.

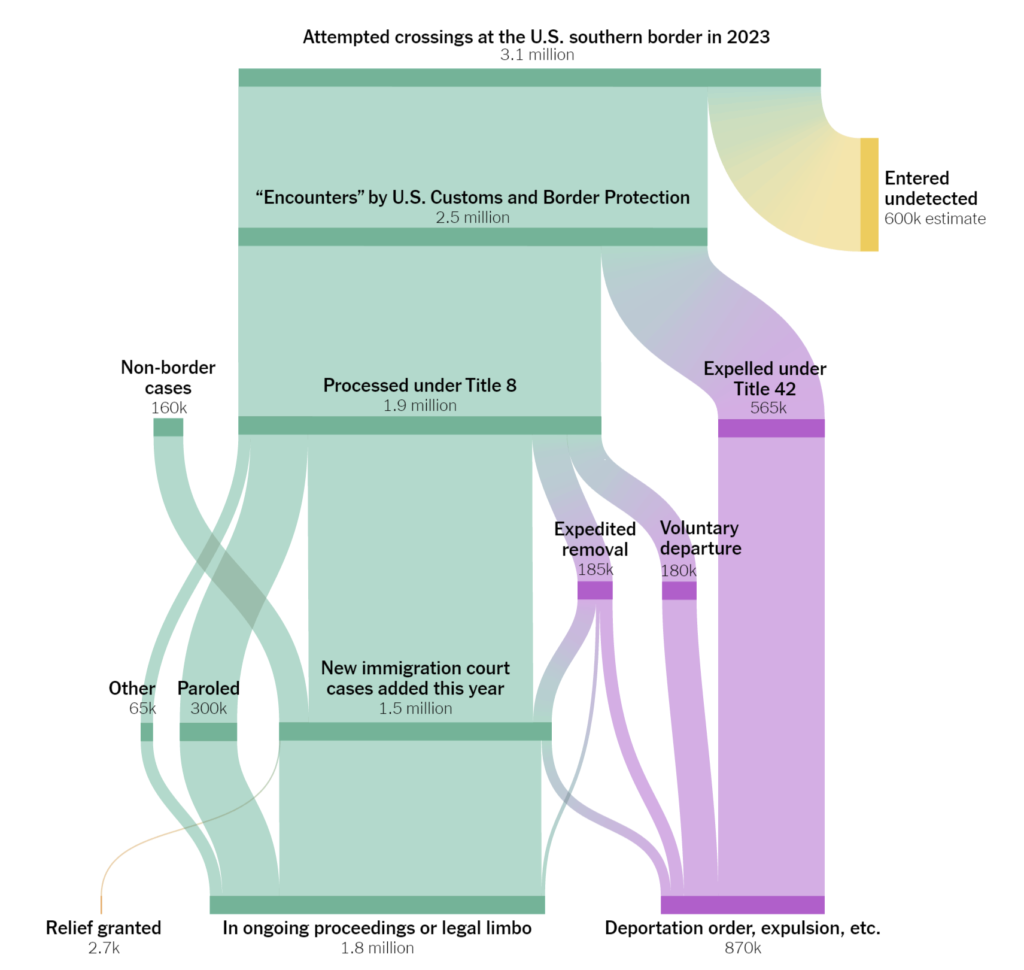

Between October 2022 and September 2023, there were 3.1 million attempted crossings along the U.S. southern border.

Of that, an estimated 600,000 migrants were able to cross the border undetected, according to the Department of Homeland Security.

The U.S. government had 2.5 million migrant “encounters”, 83 percent of which occurred between designated ports of entry, often in dangerous, remote locations like the Sonoran Desert.

Over half a million migrants were expelled under Title 42, a policy enacted during the pandemic that allowed border officials to expel migrants without a deportation hearing. The Biden administration lifted the policy in May 2023.

Most were processed under Title 8 immigration law, which covers a wide range of issues, including asylum, visas, refugees and deportations.

Almost 200,000 were placed into expedited removal proceedings, usually because of a criminal record or a prior border apprehension. Others voluntarily left to avoid further processing.

Roughly 300,000 migrants were given humanitarian parole at the border and allowed to temporarily live in the United States — a status available to migrants from a handful of countries such as Venezuela and Nicaragua.

Including migrants who were apprehended elsewhere or were referred after other proceedings, nearly 1.5 million new cases were added to the immigration court system in the last fiscal year.

Only a small number of new cases were decided in the year they were added. As of the end of 2023, some 1.8 million of the new arrivals remained in the United States with their case waiting in the backlog or with some other form of temporary status.

A minute fraction of new court cases ended in a deportation last year. But nearly 900,000 migrants were removed through other channels.

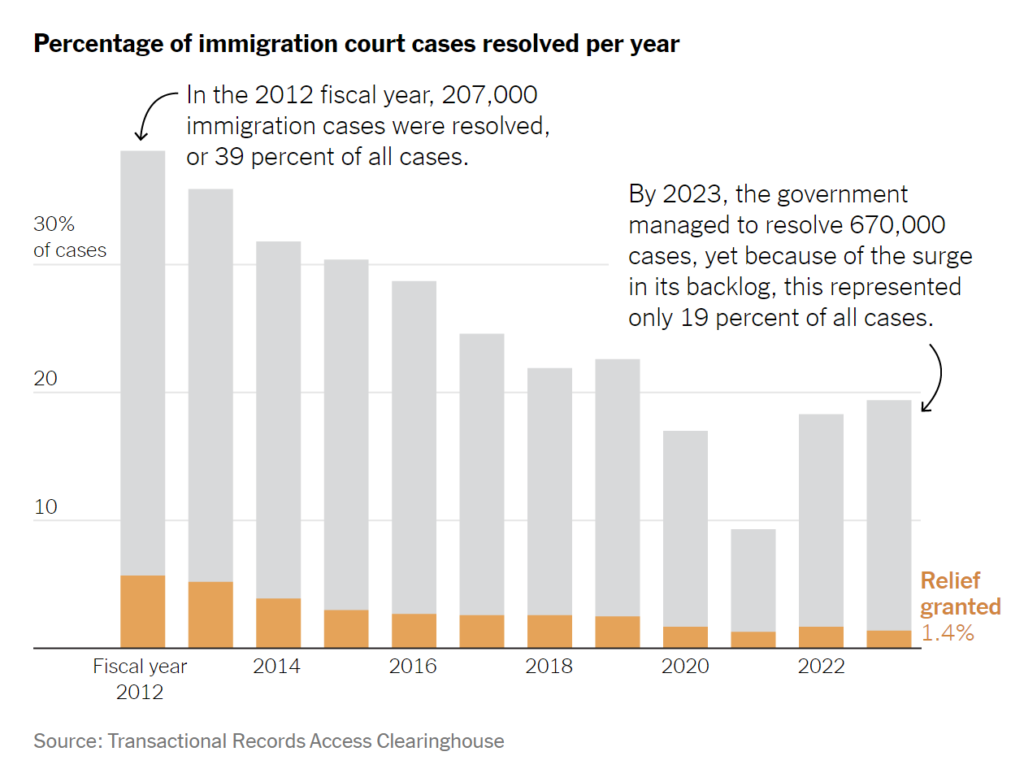

Of the nearly two million migrants who were processed under Title 8 last year, just 2,700 were granted formal relief in the form of asylum and other paths towards permanent residency.

***

The recent surge of migrants at our southern border, which reached a high in December, has, at long last, brought Democrats and Republicans closer to agreement on one thing: the need for immediate attention to our broken immigration system.

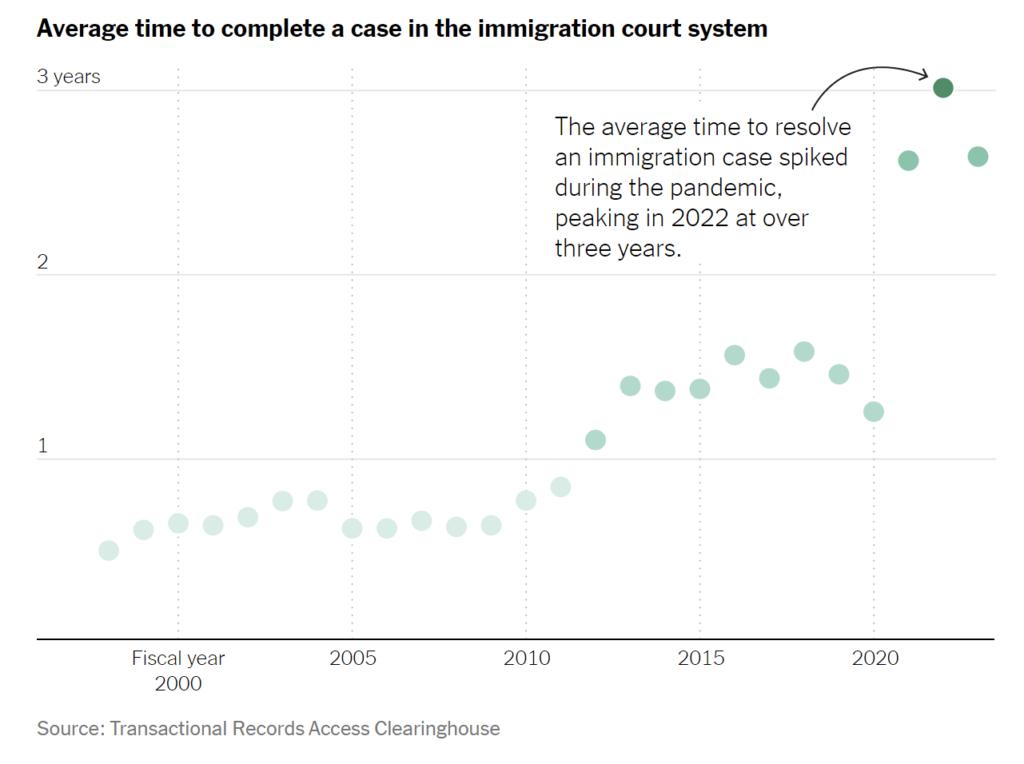

We have an underfunded immigration apparatus that is swaddled in bureaucracy, complicated beyond imagination, bound by decades-old international agreements, paralyzed by divisive politics and barely functional under the best of circumstances.

Now we face the terrible consequences. In fiscal year 2023 alone (from October 2022 to September 2023), the United States had two and a half million “encounters” along its 2,000-mile border with Mexico, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. That is over two and a half times the number just four years ago, overwhelming the ability of governmental bodies — border patrol, immigration courts, human services agencies — to manage the flow.

The continued escalation of the crisis has allowed Republicans to leverage the issue in exchange for more aid for Ukraine and Israel, which in turn has pushed a bipartisan group of senators and White House officials into marathon negotiations.

Broadly speaking, Democrats want more money to process the backlog while Republicans want to substantially narrow the grounds on which migrants would be permitted to remain in the United States (along with building more of the wall that Donald Trump has been urging). We need lots of the former and a bit of the latter.

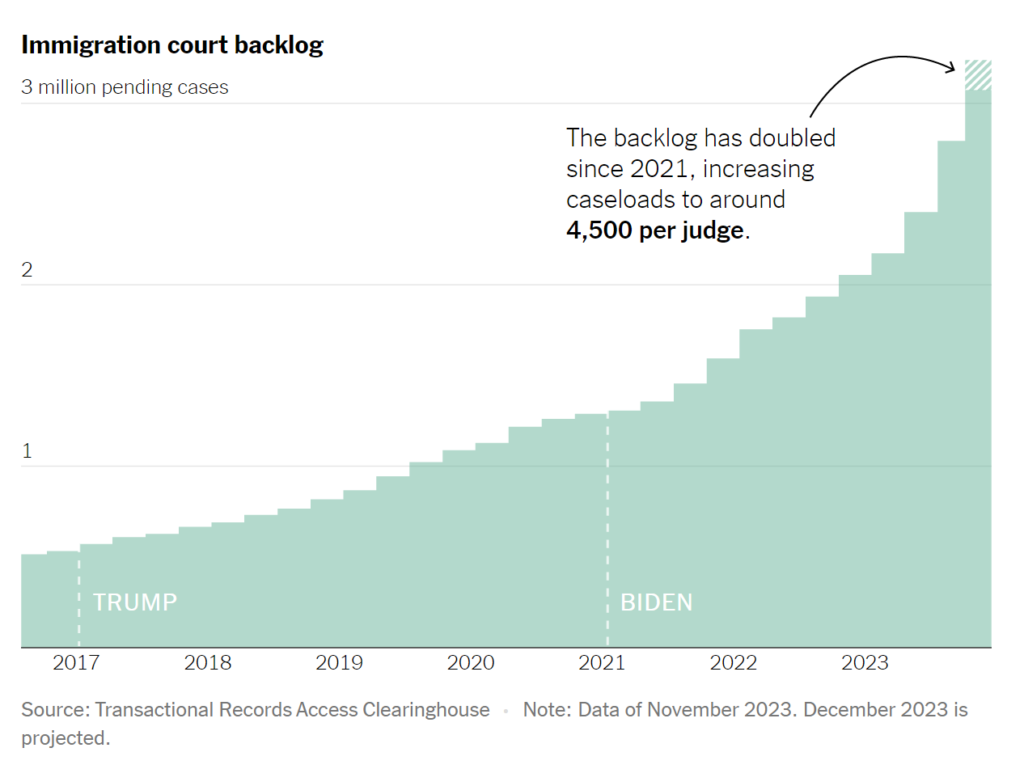

The Democratic push for more funding is correct. The country’s immediate need is to unclog the immigration court system that has allowed millions of asylum seekers to float around the country, unable to work for the first six months after entry and then potentially remain in limbo for years. During the 2023 fiscal year, just 670,000 cases were resolved in the courts.

So, yes to money for more border agents, processing staff, asylum review officers and judges.

But that’s not enough. We must reduce the flow to the border, which will require making immigrating into the U.S. by such means more difficult. As Republicans have long demanded and Democrats are coming to see as necessary, our obligation under international law to provide asylum need not create chaos.

For starters, we should require asylum seekers to apply in Mexico or other countries, including their home countries, before they reach the U.S., reducing the incentive to travel here to gain entry during drawn-out proceedings. Both Mr. Trump and Mr. Biden have tried to accomplish this, but these changes have been mired in legal challenges and strained negotiations with Latin American countries. For this to succeed, the United States needs to work with Mexico to make conditions there safe for asylum seekers in waiting.

Next, we need to tighten the asylum criteria.

For example, we should make a greater distinction in the asylum process between those who followed established procedures and entered the country through an established port of entry and those who crossed along our border between ports of entry.

Mr. Biden has already started down this path, with a new federal rule requiring migrants to obtain appointments at ports of entry (or show they’ve been denied asylum in another country) to be eligible for the standard path to asylum. Others will face far tougher criteria to gain relief.

This rule is being challenged in the courts, and it needs to be codified by Congress as part of the current negotiations.

While recognizing the need for due process, we should raise the legal standard for consideration for asylum from a “significant possibility” that asylum would be granted to something closer to the standard used for final decisions in immigration court, reducing the number of duplicative hearings and administrative delays.

We may also need to further limit the use of humanitarian parole, a program expanded by the Biden administration that allows more migrants from places like Venezuela and Nicaragua to temporarily enter the country and apply for relief. As heartbreaking as it may be, we simply cannot take every refugee from every failed state.

Of course, the most humane way to reduce the flow to our border would be to help improve conditions in the countries from which many of the new arrivals emanate. But we chose differently: Over the past 10 years, our aid spending has dropped to a paltry 0.2 percent of our gross domestic product, from 0.3 percent.

In the long run, we need to come to a national consensus on how many immigrants we want to accept and the bases for determining who is chosen. That includes balancing the two principal objectives of immigration policy: to meet our legal and moral humanitarian obligations to persecuted individuals and to bolster our workforce.

Without immigration, our population would begin to decline in 2037, according to United Nations projections. Even continuing to admit a million legal immigrants a year would leave our population flatlining within half a century. Maintaining our historical population growth rate of 1 percent would suggest admitting nearly four million individuals a year.

While that may be more than today’s politics can withstand, we should care about keeping the number of Americans growing at a reasonable rate. Immigration is our defense against the challenges of an aging society. Fewer workers supporting more retirees makes it harder to adequately fund Social Security and Medicare.

Given that unemployment is at 3.7 percent, near the all-time low, no one can sensibly argue that these additions to the labor force would cost Americans jobs. Increasing legal pathways would also help reduce the illegal labor that endangers migrants and undercuts American workers.

Moreover, reshaping our immigration policies to prioritize skills that are in particularly short supply would be a win-win. At present, only 27 percent of green card recipients are chosen for their skills. And we still don’t automatically provide green cards to non-Americans who graduate from our universities. That is insane.

A better immigration system is possible. With the right policy, resources and political will, we can live up to our country’s ideals and still maintain a safe and orderly southern border.