Originally appeared in the New York Times.

Medicare for All. The Green New Deal. Free college tuition.

With each new entrant into the Democratic presidential sweepstakes comes a fresh cascade of ambitious social programs to entice and excite would-be supporters.

The list of “payfors,” to use a bit of Washington jargon, grows more slowly. They’ll pay for this how, again? Tax the rich, tax the rich — or take cover behind a convenient bit of progressive dogma: Don’t worry about the fiscal impact because America’s rising budget deficits and debt levels don’t much matter.

That’s a scary drift of thought, and it should set off alarm bells for all Americans. Vast increases in debt will ultimately compromise Washington’s ability to maintain its current array of spending programs, let alone add new ones, and threaten our standard of living.

A short history: While Republicans once were the party of fiscal responsibility, President Ronald Reagan threw that out the window by embracing enormous tax cuts justified by a fiction: the idea that the resulting growth would more than pay for them.

More than a decade later, President Bill Clinton nursed the budget back into surplus, only to have President George W. Bush force through his own tax cuts. His vice president, Dick Cheney, once reportedly said, “Reagan proved deficits don’t matter.”

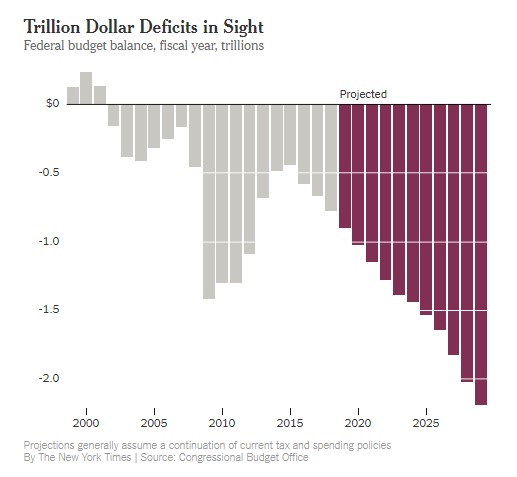

That attitude, plus the puncturing of the dot-com bubble, two wars and a financial crisis, brought us our first $1 trillion gap in 2009. But by 2015, President Barack Obama had whittled the deficit down to $439 billion.

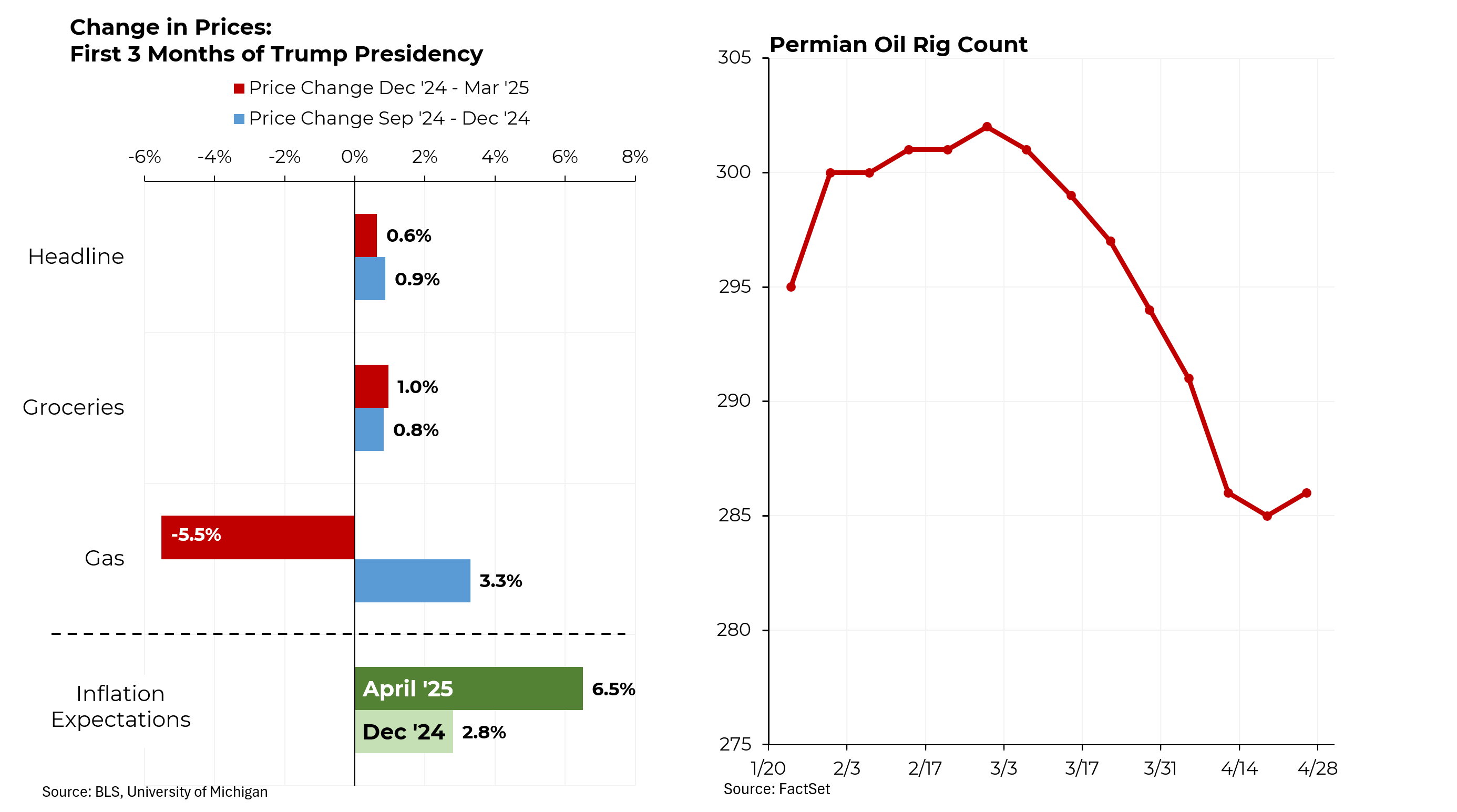

Then came President Trump, with his vast tax cuts along with a bipartisan move to abandon spending restraint with the fiscal 2018 budget. The resulting legislation added $400 billion to the deficit, according to an estimate from the Committee for a Responsible Budget, and the consequence is a deficit for the current fiscal year of nearly $900 billion.

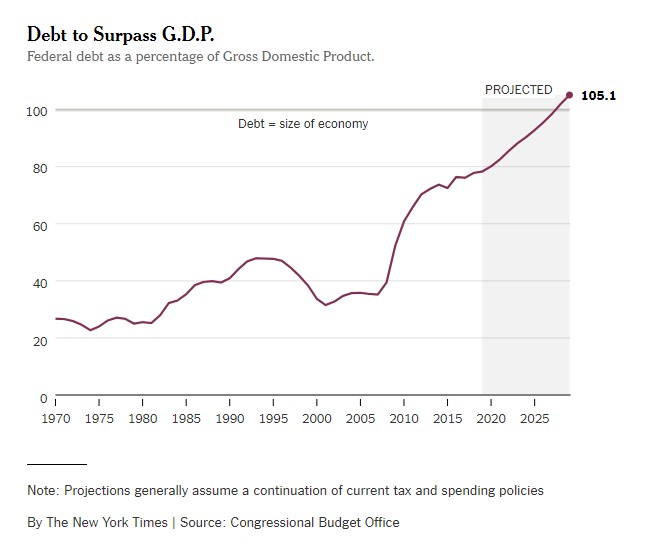

On present course and speed, the United States is on track to experience the highest deficits in its history, reaching more than $2 trillion a year by 2029. Those annual gaps are projected to bring America’s total debt to nearly $33 trillion by that date, according to the Committee for a Responsible Budget. That’s double today’s level and more than the size of our economy, a peacetime record.

One concern often raised by deficit hawks is that so much borrowing by the government could force interest rates higher, making it harder for businesses to borrow and reducing the amount of capital available to the private sector. In the worst case scenario, they fear that credit markets could partially or completely shut down, putting a hard brake on the economy.

While that’s not impossible, my principal fear is that all this irresponsible borrowing amounts to intergenerational theft. America is simultaneously indulging in two deficit-busting desires: for lower taxes and for robust government programs. Eventually, the interest on all the debt will force the governments of future generations to reverse those fiscally imprudent policies in order to pay for today’s profligacy.

It’s like a couple in their 40s deciding to borrow money to sustain a lavish lifestyle and then leaving the debts for their kids to pay off after they’re gone.

But that’s not all. The generally accepted measure of America’s national debt doesn’t include obligations for future retirement and health care benefits.

In a perfect world, those programs would function like insurance; each generation’s annual premiums would pay for support received during its golden years. That principle was abandoned long ago. Based on the current demographics of the American population, we would need to set aside $49 trillion to make the Medicare and Social Security Trust Funds truly solvent.

Meanwhile, progressives argue that certain kinds of spending are, in reality, investments that will bring large dividends in the future. With interest rates still near historic lows, they contend that the returns from borrowing for these investments would greatly exceed interest costs.

While that’s true, deciding what is an investment and what is just an expense with no potential return would inevitably become a political debate. Democrats and Republicans might quickly agree about investing in building roads and bridges but what about spending on education? Should that be considered an investment? What about work force training or research and development? I fear that in the end, many spending programs would be classified as investments simply to make the budget deficit appear smaller.

Regardless, taxes need to go up, starting with unwinding the Trump tax cuts for individuals, which favored the rich. Next, we should take a tougher look at corporate taxation. Reducing the corporate tax rate to maintain our global competitiveness made sense, but it didn’t need to go all the way from 35 percent to 21 percent.

Then there are potential new sources of tax revenue. I’ve expressed support, for example, for eliminating the special treatment of capital gains and dividends. Let’s also reform overly generous estate tax provisions. While I’m all for putting most of the burden on the rich, we need to be mindful of realistic boundaries to ensure that tax avoidance or even expatriation don’t start to rise.

On the spending side, unfortunately, taking a hard look at the entitlements programs is essential. I’m not suggesting eviscerating them, but ideas like modestly raising the retirement age or scaling benefits based on need should be explored.

Even implementing all these adjustments won’t prudently provide room for expansive new social programs. Adopting those would require still tougher choices about raising taxes and trimming spending.

If we care about our kids and the country we are leaving them, Americans will make these tough decisions instead of continuing to duck them.