Originally appeared in the New York Times.

Steven Rattner responds to readers who have doubts about his plan to raise revenue from the uber wealthy.

Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is calling for a steep increase in the tax rate of America’s top earners to help level income inequality and raise revenue for the deficit. But in his Op-Ed “A Better Way to Tax the Rich,” Steven Rattner, a contributing opinion writer and Wall Street executive, says there are “more sensible” ways for the wealthy to contribute, “in particular, by increasing the tax rate on capital gains and dividends and closing loopholes.”

Readers responded, many challenging Mr. Rattner’s suggestions and offering alternatives. We asked him to follow up with some of them. A selection of those comments, along with his responses, are below, edited for length and clarity. — Rachel L. Harris and Lisa Tarchak, senior editorial assistants.

Jim, Pennsylvania: And herein lies the value of radicals like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez: they scare the wealthy back into the sensible center. Never forget that the powerful in America only make concessions as a way to fend off even greater sacrifices being forced upon them.

Steven Rattner: There’s some truth to that! As I indicated in the opening paragraph of the Op-Ed, I believe that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has done the country a service by pointing out that the wealthy need to pay more. Just the other day, Jamie Dimon, the superb chairman and chief executive officer of JP Morgan Chase, said he would be willing to pay higher taxes, as long as the “dollars are going where they can be most effective.”

Dennis Callegari, Australia: A 70 percent tax on earnings over $10 million per year, or tax investment income like ordinary income? Why not both?

Steven Rattner: I have no problem increasing taxes on the rich and I have no problem doing that as a combination of increasing taxes on ordinary income above $10 million and raising capital gains tax rates to the current 37 percent rate on ordinary income.

I’ve been in the working world for more than 40 years, in tax regimes where my marginal rate on earned income was as high as 50 percent and as low as 28 percent (which puts the current 37 percent somewhere near the middle).

Contrary to the argument of supply-siders that high marginal rates discourage work, I’ve never believed that my work ethic varied as the marginal tax rate went up or down. That said, I would agree that there is some tax rate above which individuals either work less or try harder to avoid taxes.

It seems to me that a combined 82.7 percent marginal rate for those of us who live in high tax states like New York is a bridge too far. In addition, it would put us well above the highest tax rate of any developed country.

Veronica, Brooklyn: The whole point of Ocasio-Cortez’s plan, and similar proposals, is to tax specifically and only the rich, because they are the ones who are perceived as having inequitably and unjustly profited from the existing capitalist system. The problem with Mr. Rattner’s proposal is that it would hit middle-class retirees who depend on investment income either directly or indirectly through pension funds.

Steven Rattner: That’s a fair point. A couple of thoughts in response. First, my proposal would not affect retirees who depend on pension plans, either the corporate type or the individually directed type. Neither pays capital gains or dividend taxes; when the benefits come out, they are taxed as ordinary income. My proposal would affect retirees who hold investments directly and recognize capital gains and (or) dividends.

Unfortunately, the world is not perfect; I would note that most capital gains taxes are paid by the wealthy. The top 1 percent accounted for 69 percent of reported long-term capital gains in 2018; the top 0.1 percent (average income over $10 million) accounted for over half.

Lastly, taxing capital gains and dividends as ordinary income would mean that individuals would pay taxes based on their income level; thus those of more modest means would pay less than the current 37 percent top rate and potentially less than the 23.8 percent capital gains and dividend rate now in effect.

David Underwood, Citrus Heights: My wife and I both saved from hourly incomes. She does not have a pension. I took a short-term payout and invested it. Some of my investments are in I.R.A.s. I have to take out a distribution each year at the regular income rate. Just like the G.O.P. tax scam, this plan won’t hurt the wealthy, but it will hurt small investors, like me. Taxes should take into account the actual income, not focus on dividends and capital gains.

Steven Rattner: I would reiterate that under my proposal, the capital gains and dividend rate would vary based on income, just as the rate on wage income varies. So retirees with lower incomes would pay less than the wealthy do and possibly even less than they currently pay.

Padfoot, Portland, Ore.: Taxing all capital gains and dividends would be a mistake. I’m not saying that the cutoff should be at $10 million, but give the small investor a break. Let them get a reduced rate for capital gains and dividends for the first $10,000 or so. This would benefit the many and not affect the real targets of this tax change.

Steven Rattner: This is a constructive suggestion, and I’d be happy to see a revamped capital gains and dividend policy provide for an exemption for the first $10,000 or possibly even more for Americans with incomes below some reasonable threshold.

Dan S, Eden Prairie, Minn.: Why not make capital gains taxes progressive regardless of whether they’re treated like regular income?

Steven Rattner: As I noted, by taxing capital gains and dividends as ordinary income, we would effectively be making them progressive; a taxpayer’s rate on this form of income would be the same as what he paid on his wage income.

fbraconi, New York: It is a mistake to assume, as Rattner does, that the cap on deductibility of state and local taxes is now a permanent feature of our tax codes. The limitation of the state and local tax deductions was Mitch McConnell’s spit-in-the-eye to the blue states. It has been a target of conservatives for decades because they know that ending or limiting it will inhibit Democratic leaning states from undertaking progressive policies to address housing and homelessness, education, public transportation and other pressing problems. Repealing the caps must be a priority for Democrats when they regain control of the federal government.

Steven Rattner: Unfortunately, it’s impossible to address every aspect of the tax code in the space allotted. I certainly agree that the deduction on state and local taxes was a smack by the Republicans at the blue states. But we shouldn’t kid ourselves about the near-term likelihood of this deduction being restored. First, the Democrats would have to retake the Senate, which obviously cannot happen before 2020 at the earliest and even then, has a less than 50/50 chance of occurring.

Democrats would also need the White House, which could well happen in 2020 but is obviously not guaranteed. If all the ducks lined up as I just described, I would imagine that restoring the state and local taxes deduction would be near the top of the “to do” list.

JW, New York: I’d like to add one more aspect: Remove the income ceiling on Social Security tax so that more money goes there. It’s ridiculous to keep hearing arguments about how Social Security will go bankrupt when there’s this simple change available that Congress refuses to consider. It may not fix the problem entirely, but imagine how much would be added from all those hedge fund managers who make $1 billion or more a year on top of those with stock option gains in the hundreds of millions.

Steven Rattner: I agree with the general concept that it is time to rethink how we finance Social Security. It was originally designed as an insurance program, in which the maximum amount of tax payable and the maximum benefits were linked. However, the Social Security Trust Fund has been underfunded since 2010 and is currently projected to be exhausted by 2034.

We could lift the cap entirely, as you suggest, but in that case, we would want to be judicious about raising the top marginal rate, for the reasons I discussed above. In the end, it’s more or less the same dollars, whether we raise them by lifting the Social Security cap or raising the top marginal rate on ordinary income.

Dr. J., New Jersey: As the graph shows, the real villain here is Ronald Reagan. Reagan caused this country more long-term economic harm than any other president, including Coolidge and Hoover. Despite the best efforts of President Clinton, we’ve never gotten taxes on the rich back up to healthy, pre-Reagan levels.

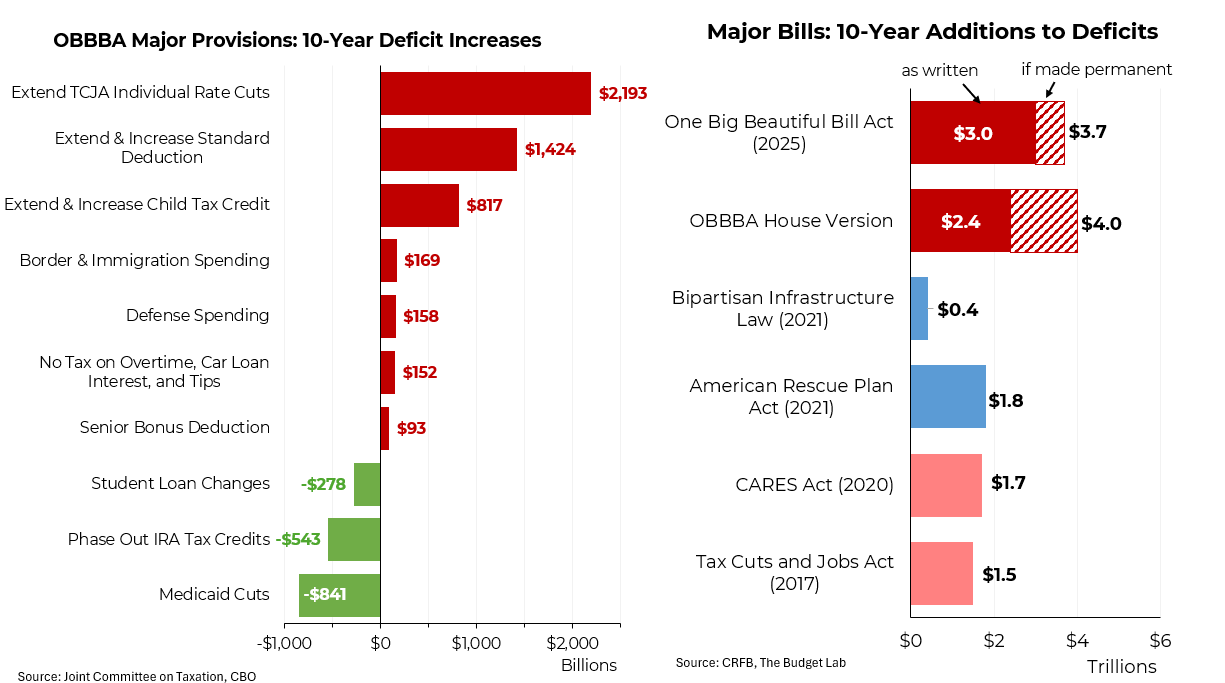

Steven Rattner: Agree in part and disagree in part. I agree that Reagan’s tax legislation lowered the top rate excessively (to 28 percent from the previous 50 percent). What was even worse was that Reagan’s embrace of supply side dogma was heavily responsible for the shift in sentiment toward the idea that large federal budget deficits are not a problem. Even after President Clinton balanced the budget near the end of his time in office, President George W. Bush passed irresponsible tax cuts that brought back large deficits.

Vice President Dick Cheney was famously reported to have said in an Oval Office meeting, “Deficits don’t matter. Reagan proved that.” Then, using similar justification, the Trump Administration added more tax cuts and spending increases that exploded the deficit, as I previously noted.

Where I disagree is that Reagan did some things that were constructive. His push for deregulation, while sometimes excessively favoring business interests, was important to reviving the economy. And the bipartisan Tax Reform Act of 1986 simplified the code and eliminated a lot of loopholes and tax avoidance schemes.

Think, Wisconsin: There are other ways to increase federal revenues that are not mentioned in Mr. Rattner’s Op-Ed. Reform the estate tax system; treat corporations as “individuals” when it comes to income taxes, not just when it comes to political contributions; review and revoke nonprofit status for organizations that are not serving the public good, as happened with the N.F.L. It’s time the fat cats of our country begin paying their fair share, for once.

Steven Rattner: First, with respect to estate taxes, I agree that reforms are badly needed. The 2017 tax reform legislation amazingly increased the size of the exemption for each individual from $5.6 million to $11.2 million ($22.4 million for married couples). That should never have happened. In addition, careful thought should be given to the current policy that assets held at death are not subject to capital gains tax. That means heirs can receive, potentially, billions in appreciated stock or real estate assets and then sell them without paying any capital gains taxes on the profits.

Second, I am sympathetic to the view that taxing corporations at 21 percent while the top rate for individuals is 37 percent is simply not just. But unfortunately, we live in a global world and our competitors — other countries — have been lowering their corporate rates to attract more business. My proposal would, in effect, make wealthy Americans who own stocks pay more to offset the cuts that we made in the corporate rate.

Third, I’m not an expert on the tax status of nonprofits but I’m certainly open to learning more about this. On a related front, we should also have a discussion about the deduction for charitable contributions. This has the same effect as if the government had a matching plan for charitable contributions. I’m as much in favor of charity as the next guy but I’m not sure why the government should be in the business of providing subsidies of this sort.