Tariffs don’t work the way Trump seems to think they do.

Originally published in the New York Times

Eager to shore up weakening markets and economic data, President Trump has unveiled the first phase of what he calls the “greatest and biggest deal ever made” with China.

More a shaky truce than a final accord, the latest development in the president’s trade war has nonetheless again elevated the murky subject of international commerce to the front pages.

Yet few Americans — including the president — understand how global trade works, both how it can help our economy and how some can be left behind.

Let’s try to unpack a few of the complexities.

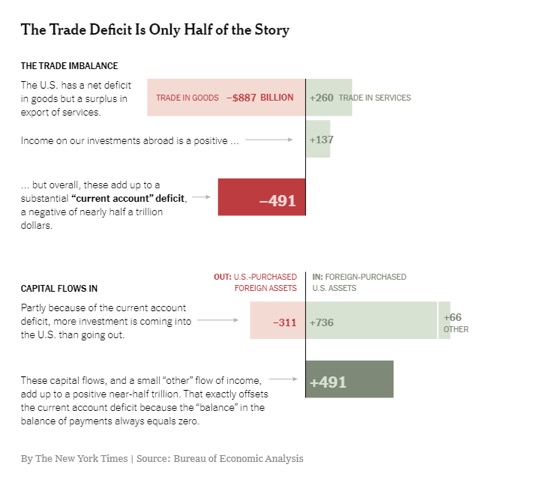

For starters, when Mr. Trump talks about the “trade deficit,” he is almost always referring to just imports and exports of physical goods. But international commerce is much more complicated than that. In addition to goods, we trade in services (entertainment and tourism, for example), in which we have a surplus with China and with the world.

Then there’s income on foreign investments (and income paid to foreigners who hold assets here). That’s also a positive, largely because our foreign holdings earn a higher rate of return than what non-Americans earn on their investments in the United States.

Those three items add up to the “current account,” the measure that economists most often refer to. At a $491 billion deficit, it’s about half of what Mr. Trump regularly — and incorrectly — cites as our trade gap. Of this amount, China is estimated to account for only about half (and by the way, notwithstanding Mr. Trump’s histrionics, the current account deficit has been increasing on his watch).

After that comes investments made by American entities overseas and then the reverse. More about that later because it is complex and controversial: Are we becoming more indebted to foreigners, and should we be happy that they are investing here?

But in the end, the balance of payments must always be zero.

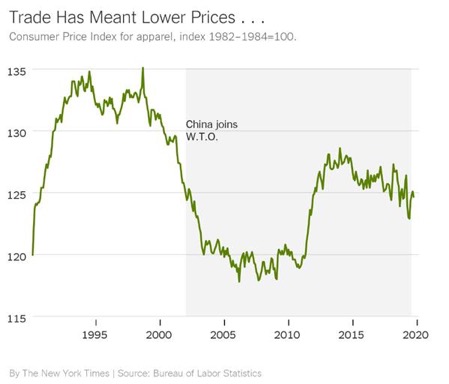

Basic economics tells us that if another country can make something more cheaply than we can, we should focus our efforts on products we make less expensively and then trade them for the other goods or services. That’s happened in spades in the post-World War II period. The result, for virtually all Americans, has meant lower prices.

For example, the price of apparel dropped by 12 percent between July 1998 and February 2006, aided substantially by China’s joining the World Trade Organization in 2001. (The rise in prices in 2011 shown in the chart below resulted from poor world cotton crops.)

You can see a similar pattern in other products that typically are imported: home furnishings, toys, sporting goods, household appliances.

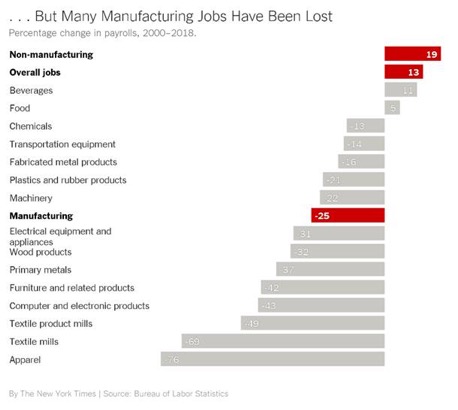

While the benefits of growing trade have been shared broadly, the costs have been concentrated among a minority of Americans who worked in industries disrupted by the shift from domestic production to imports.

To be sure, some of the job losses in this chart can be attributed to automation. But the bulk represent the effects of imports. Today, for example, 99 percent of all shoes sold in America are imported (70 percent come from China) and employment in domestic footwear manufacturing has contracted by more than 80 percent over the past 25 years. This trend gives rise to the understandable fears about the impact of trade on our manufacturing sector. One important study found that imports from China cost 1.4 million factory workers their jobs between 1995 and 2011.

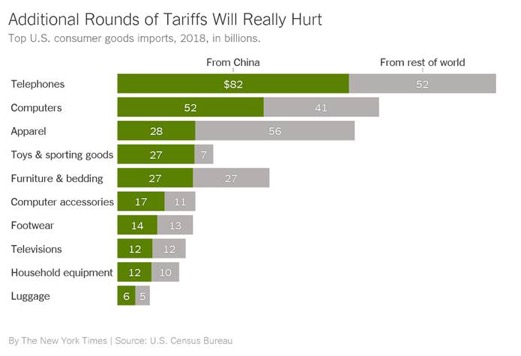

Now we’re feeling the effects of Mr. Trump’s tariffs (and the unsurprising reciprocal retaliation) in stagnant global trade. If I’ve convinced you that growing trade means lower costs for America consumers, then you should believe that flattening or declining trade has the opposite effect.

Since Mr. Trump began imposing tariffs over a year ago, American exports to China (principally soybeans and cars) have fallen by 21 percent from their peak in July 2018. That’s in part because the Chinese government, which exercises significant control over economy, can simply decide to stop buying products like soybeans. Meanwhile, American imports of Chinese goods have dropped by only 8 percent from their peak last October.

The timing of Mr. Trump’s announcement was not a coincidence; another round of tariffs was set to be imposed on China this week, and still yet more levies are planned for Dec. 15. These new tariffs would be especially painful, hitting many consumer goods that the United States buys from China, including nearly 85 percent of all toys sold here.

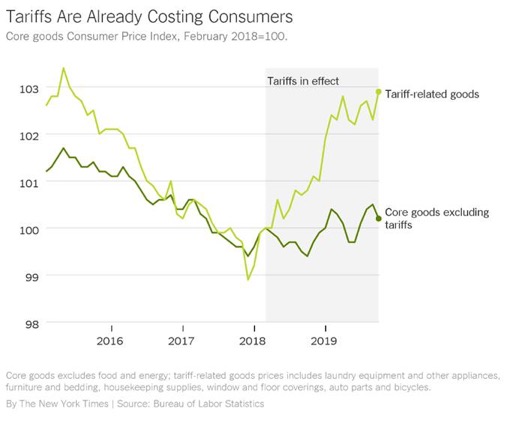

Not convinced yet about the cost of tariffs to American consumers? Take a look at what’s already happened: Since Mr. Trump began imposing tariffs in February 2018, the prices of affected goods like appliances and furniture have risen by 2.9 percent while the prices of other goods (not including food or energy) have barely increased. That’s partly because among other pernicious effects, tariffs provide room for domestic producers to raise their prices.

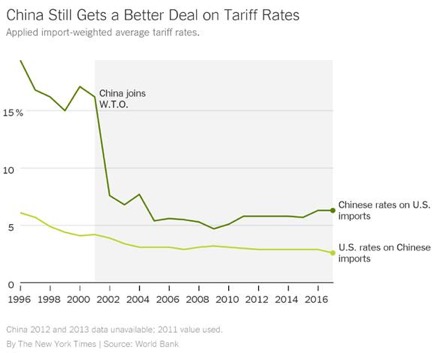

While the details of Mr. Trump’s agreement have yet to be unveiled, it is not expected to include a full leveling of the playing field. China was admitted to the World Trade Organization in 2001 as an emerging nation, entitling it to impose higher tariff rates (among other things) than those afforded developed countries. China’s economy is now the second largest in the world, but that disparity persists; our permitted tariffs on Chinese products are less than half of what China is allowed on ours.

As noted earlier, in the end every country’s balance of payments must always be zero; whatever deficit or surplus exists in the current account must be offset by a flow of capital.

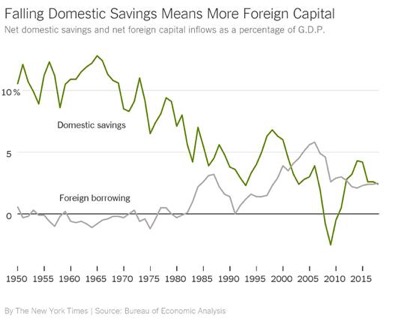

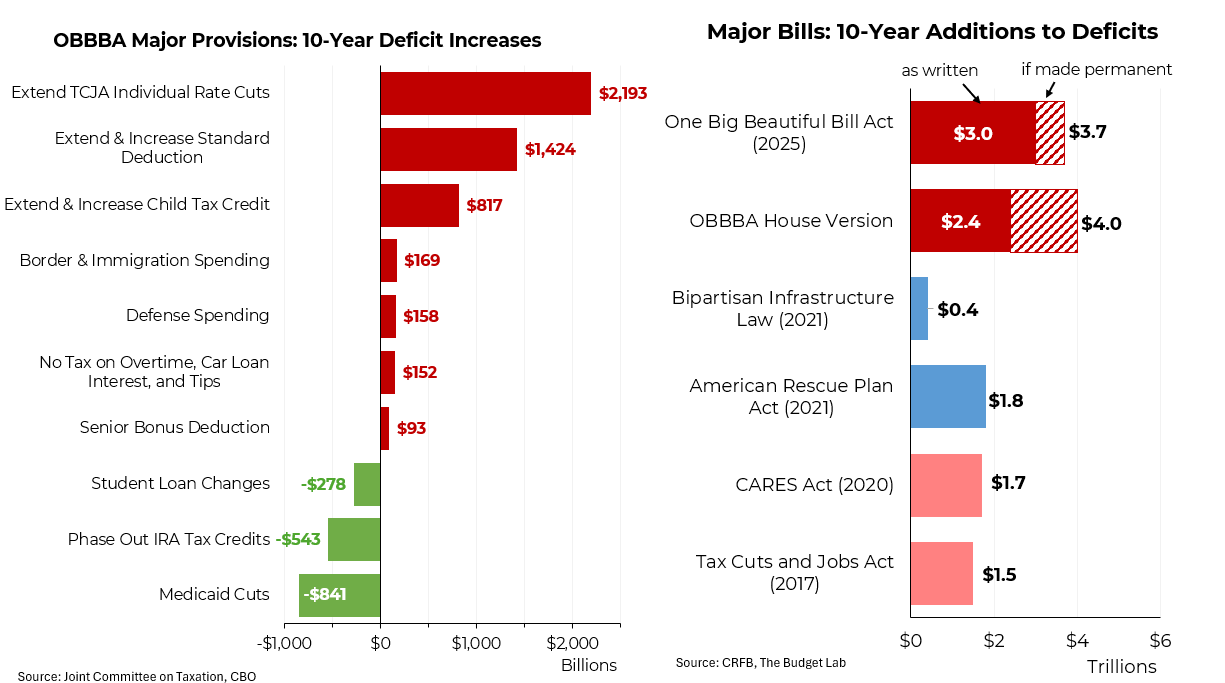

This is where the arguments over trade deficits get tricky. To supplement savings, capital can be imported for investment, as was done by the United States in the 19th century to build the railroads. But capital can also be imported to make up for a lagging savings rate and even to finance consumption. With the domestic savings rate low (in part because of a federal budget deficit about to eclipse $1 trillion), we have — in most recent years — been net borrowers.

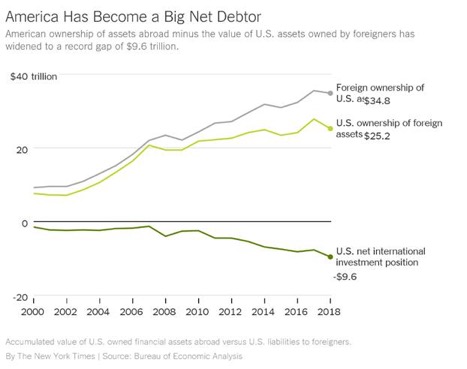

That has increased how much more foreigners own of our assets than we own of theirs. Until the last decade or so, the difference was marginal. But because of the fall in our savings rate, the gap has widened to a record $9.6 trillion. And on present course and speed, it will continue to grow.

That’s what Mr. Trump should be worried about and what he should be focused on: increasing our wealth, in large part by reducing the federal budget deficit and providing incentives for Americans to save more.