It’s time for a reality check on Trump’s claims about jobs, wages and economic growth.

Originally published in the New York Times

Recession fears may be seeping into the national conversation, but President Trump continues to boast about how great the American economy is — “the best in the world, by far,” Mr. Trump tweeted a few days ago.

Time for a reality check on Mr. Trump’s economic accomplishments, using two key measuring sticks: how well the economy is doing, compared with its performance under President Barack Obama’s leadership, and whether it has performed up to Mr. Trump’s promises.

The short answer is, the economy’s performance is not much different than it was under Mr. Obama and far short of what Mr. Trump pledged.

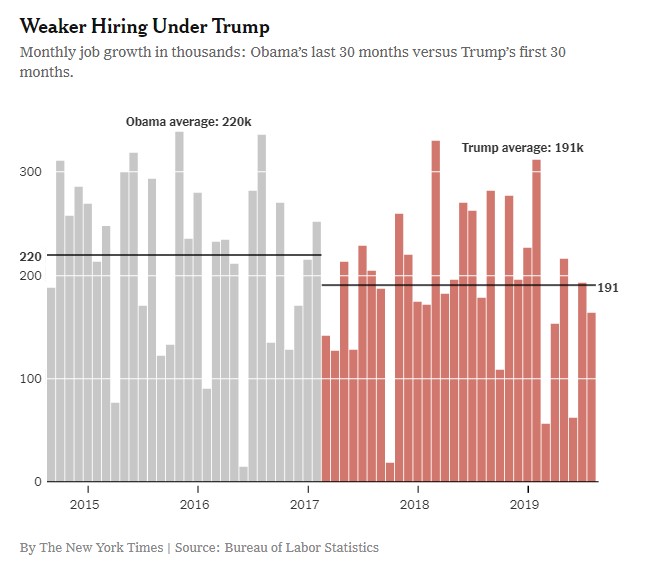

Take, for example, the all-important matter of jobs. Yes, many unemployed Americans are back on the payrolls. Yes, the unemployment rate continues to fall, as it did under Mr. Obama. But no, the pace of hiring has not been faster than it was during a similar period under Mr. Obama and indeed, has been even a bit slower.

In the first 30 months of the Trump presidency, jobs were added at an average rate of 191,000 a month. That’s certainly respectable, although it’s still less than the increase of 220,000 jobs a month during the final two and a half years of the Obama presidency.

Moreover, on Aug. 21, the Bureau of Labor Statistics announced that it is likely to revise downward substantially payroll gains earlier this year, which could cut about 15,000 jobs a month from Mr. Trump’s tally.

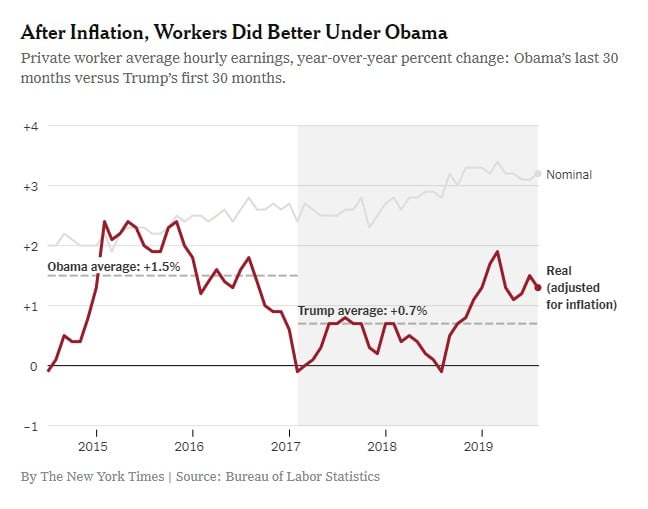

Then there are wages, the other key component of what matters financially to everyday Americans. The rate of pay raises has continued to edge up under Mr. Trump, a typical occurrence in the latter part of an economic recovery. But more important is what is left for workers after inflation takes its bite.

And on that measure, earnings for American workers rose faster under Mr. Obama.

Not to mention that Mr. Trump has utterly failed to deliver on his wage promises. As part of pushing for the 2017 tax cut, his Council of Economic Advisers projected that the legislation would raise average pay by $4,000 a worker. No material amount of that has been realized.

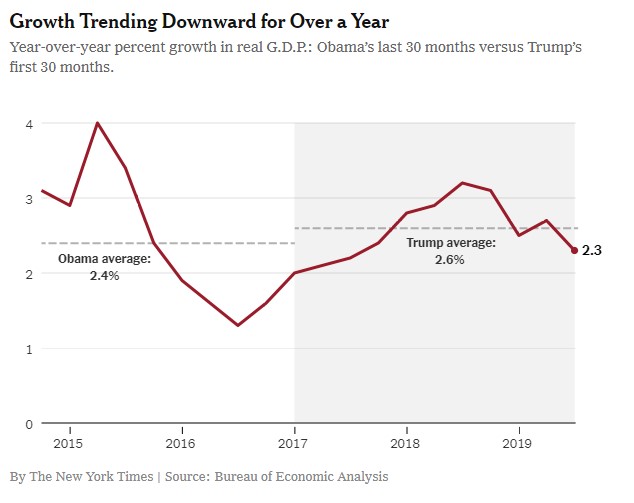

Then there’s the overall economy. The sluggishness of growth since the 2008 recession has puzzled and dismayed policymakers. During his presidential campaign, Mr. Trump routinely promised to push this rate up; in seeking passage of his tax cut legislation, he said growth would accelerate to “4, 5 and maybe even 6 percent.”

That is not remotely what transpired. The tax cut produced a short “sugar high,” a momentary boost. Gross domestic product, after adjusting for inflation, rose at a 3.5 percent rate in the second quarter of 2018. But for 2018 as a whole, the 2.5 percent increase did not come close to the Trump administration’s projection of 3 percent.

All told, G.D.P. has risen at a 2.6 rate during Mr. Trump’s presidency, which, in fairness, is marginally higher than the 2.4 percent rate of improvement during the last 10 quarters of Mr. Obama’s tenure. Neither number is anything to brag about.

Now the economy is demonstrably slowing down, thanks in large part to Mr. Trump’s trade war. Interestingly, the business community appears more worried than consumers, who have continued to spend and who, in surveys, still express confidence.

Capital investment has ceased growing (and has even fallen a bit in recent months), manufacturing output peaked last December and business sentiment is softening.

As a result, forecasters have been marking down their projections; by the end of this year, J.P. Morgan expects G.D.P. to be increasing at only a 1.8 percent rate. (The White House seems to live in a parallel universe; it clings resolutely to its prediction of 3.2 percent growth this year.)

Should that slowdown occur, expect Mr. Trump to blame the Federal Reserve and the interest rate increases it instituted beginning in December 2015. But the Fed’s increases were modest; rates are still exceptionally low by historical standards, especially in the tenth year of a recovery.

Accordingly, private economists rank the trade war as playing a much larger role in the slowing economy than the Fed’s actions. (And, of course, now it has begun cutting rates.)

“The fears of a further slowing in growth and recession are entirely due to the trade war,” Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, told me. “If the president follows through on his current tariff threats, growth will continue to weaken to well below the economy’s 2 percent potential by early next year.”

Mr. Zandi is not alone. Private economists recently polled by Reuters gave a median 45 percent probability of the United States economy entering recession in the next two years.

Economists are notoriously poor at predicting downturns. But what’s not disputable is even if we duck a recession, when it comes to the economy, Mr. Trump still has not eclipsed Mr. Obama’s record and is many miles from making America great again.