Fears were overblown for years. But let’s not be blasé about how hard it could be to halt high prices if they haunt us again.

Originally published in the New York Times.

We are all, to one degree or another, shaped by early experiences.

My father grew up during the Depression and never lost his fear of debt. I spent an early part of my career as a reporter at The New York Times, chronicling the rampant inflation that scarred the economy in the 1970s and the Federal Reserve’s struggle to contain it.

So far, the wary eye that I have kept on prices for four decades has been unnecessary. But now, with Congress poised to approve an additional $1.9 trillion in spending through the American Rescue Plan Act, I’m worrying again.

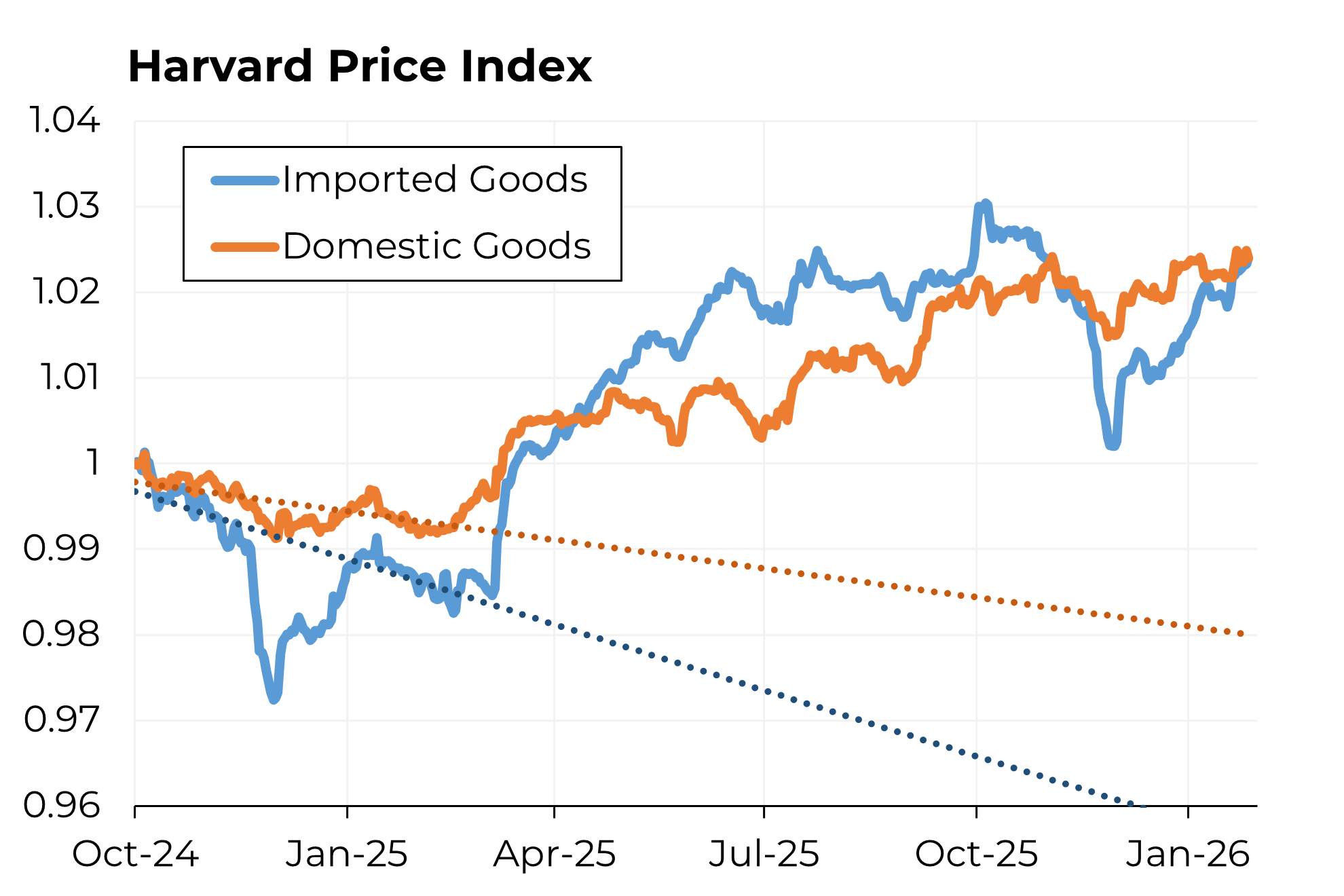

Yes, the monthly price index that tracks consumer prices continues to look benign. But even when casting aside the stimulus that the Biden administration wants to add to the economy, some important early warning signals have begun flashing.

The prices of many commodities are surging — copper and lumber because of a jump in home building. Global steel demand has pushed up iron ore prices. Even tin, heavily used in electronics, has soared as suppliers rush to meet consumer demand for new gadgets.

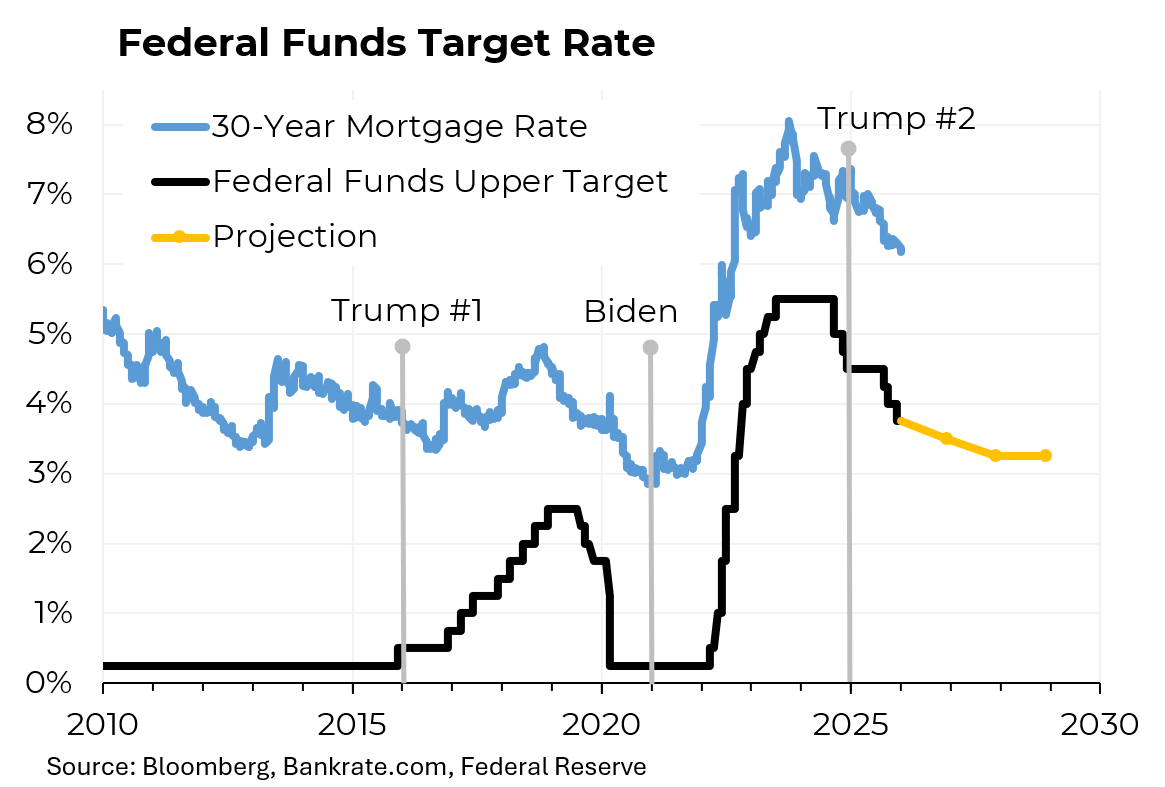

Inflation expectations are also on the rise among traders. Interest rates on long-term Treasury bonds — a reliable inflation indicator — remain historically low, but have been marching upward. That, in turn, has shaken financial markets, which rightfully view climbing interest rates as the enemy of their investments.

It is against this backdrop that Congress is on the verge of injecting an additional $1.9 trillion into an economy that has already received more than $4 trillion in boosts from Washington. According to several estimates, the measure’s spending far exceeds the extent of the shortfall in economic output caused by the pandemic.

And let’s not forget the effects of easy money from our central bank. The Federal Reserve, which has driven short-term interest rates to near zero, has also injected more money into the economy in the past year than it did fighting the Great Recession in 2008.

It’s true that, with the benefit of hindsight, we did too little to address that recession. But we are in serious danger of overreacting to this one.

Now that the Covid-19 vaccination campaign has picked up, consumers are set to unleash trillions of dollars in excess savings this spring and throughout the rest of the year. Estimates suggest that in the aggregate, U.S. families saved $1.6 trillion more this year than they normally would have. This large amount of “dry powder” was goosed by a combination of less spending in general and households that held on to the money from direct government checks.

As the pandemic, with some luck, eases, people will doubtless open their wallets and restart vacations and shopping sprees. Jobs in the service sector are already starting to come back.

Some commentators, and White House advisers, dismiss inflation fears on the grounds that the economy has fundamentally changed since the 1970s. Indeed, right before Covid-19, our unemployment rate was down to levels that in the past caused inflation to pick up.

That has led to many pronouncements that when it comes to inflation, this time will be different. “It’s better to overreact than underreact to crises” has become a conventional mantra, along with a promise that if inflation picks up too much, the Fed has the tools to deal with it.

OK — but let’s not be so blasé about how hard it would be to put that tiger back in its cage. Forty years ago, curbing the painful hike in prices took the Fed raising interest rates to 20 percent, forcing the economy into a brutal recession.

While such a catastrophe is far from guaranteed, more prudence is merited. Start with cutting back the $1.9 trillion package. When responding to critics, President Biden has asked repeatedly, “What would they have me cut?”

Fair enough, Mr. President, here’s some of what should be rejiggered:

The $422 billion in stimulus checks that will put money in the pockets of millions of Americans financially unaffected by the crisis should be replaced by much more targeted (and less expensive) efforts around those who have been directly hit with economic losses.

Policymakers should explore, for instance, income replacement programs that would help Americans who still have jobs but have had their earnings cut significantly by the pandemic — relying on changes in adjusted gross income from 2019 to 2020, as derived from tax returns.

The $510 billion in aid to states and localities (including for education) should also be dramatically reduced; the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget recently explained how Moody’s Analytics estimates only “an additional $86 billion of aid is needed to cover revenue losses.”

That assistance should also be more concentrated on where the need exists. According to Bloomberg, California’s revenues for this fiscal year are roughly 10 percent greater than expected (partly a result of soaring technology company valuations), while general-fund revenue in New York is estimated to be 11.7 percent lower than prepandemic forecasts.

And we should take a fine-toothed comb to lesser-known wasteful provisions, like giveaways to the airlines and an indirect bailout (added by the House) of multiemployer pension funds. Some of the money that we save by trimming the American Rescue Plan Act can be reallocated to one of our most pressing needs: infrastructure. Those funds get spent more slowly (and because of that put less immediate pressure on prices) and have the critical effect of helping to improve our unimpressive productivity growth rate.

Wasting precious dollars that could be better spent can’t possibly be worth the risk of igniting high inflation again.