WITH metronomic regularity, gauzy accounts extol the return of manufacturing jobs to the United States.

One day, it’s Master Lock bringing combination lock fabrication back to Milwaukee from China. Another, it’s Element Electronics commencing assembly of television sets — a function long gone from the United States — in a factory near Detroit.

Breathless headlines in recent months about a “new industrial revolution” and “the promise of a ‘Made in America’ era” suggest it’s a renaissance. This week, when President Obama gives his State of the Union address, he will most likely yet again stress his plans to strengthen our manufacturing base.

But we need to get real about the so-called renaissance, which has in reality been a trickle of jobs, often dependent on huge public subsidies. Most important, in order to compete with China and other low-wage countries, these new jobs offer less in health care, pension and benefits than industrial workers historically received.

In an article in The Atlantic in 2012 about General Electric’s decision to open its first new assembly line in 55 years in Louisville, Ky., it was not until deep in the story that readers learned that the jobs were starting at just over $13.50 an hour. That’s less than $30,000 a year, hardly the middle-class life usually ascribed to manufacturing employment.

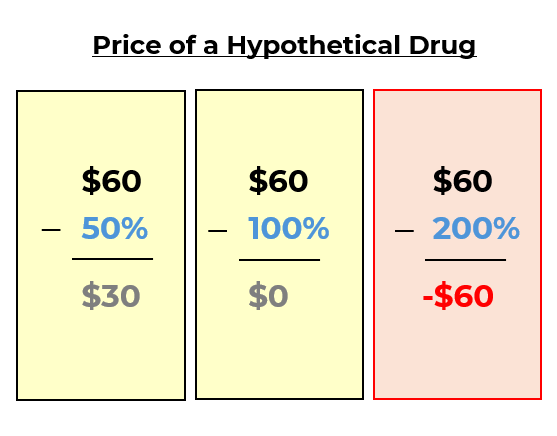

This disturbing trend is particularly pronounced in the automobile industry. When Volkswagen opened a plant in Chattanooga, Tenn., in 2011, the company was hailed for bringing around 2,000 fresh auto jobs to America. Little attention was paid to the fact that the beginning wage for assembly line workers was $14.50 per hour, about half of what traditional, unionized workers employed by General Motors or Ford received.

With benefits added in, those workers cost Volkswagen $27 per hour. Consider, though, that in Germany, the average autoworker earns $67 per hour. In effect, even factoring in future pay increases for the Chattanooga employees, Volkswagen has moved production from a high-wage country (Germany) to a low-wage country (the United States).

All told, wages for blue-collar automotive industry workers have dropped by 10 percent, after adjusting for inflation, since the recession ended in June 2009. By comparison, wages across manufacturing dropped by 2.4 percent during the same period, while earnings for Americans in equivalent private-sector jobs fell by “only” 0.5 percent. (To be fair, including benefits, compensation for manufacturing workers remains above that of service employees.)

These dispiriting wage trends are a central reason for the slow economic recovery; without sustained income growth, consumers can’t spend.

Low wages are not the only price that America pays for its manufacturing “renaissance.” Hefty subsidies from federal, state and local government agencies often are required. Tennessee provided an estimated $577 million for Volkswagen — $288,500 per position! To get 1,000 Airbus jobs, Alabama assembled a benefits package of $158 million.

Now Boeing has just used the threat of moving to a nonunion, low-wage state to win both a record subsidy package — $8.7 billion from Washington State — and labor concessions.

Over objections from their local leadership, union workers approved a new contract that would freeze pensions in favor of less generous 401(k) plans, reduce health care benefits and provide for raises totaling just 4 percent over the eight-year term. (Boeing’s stock price rose by over 80 percent last year.)

FOR all the hoopla, the United States has gained just 568,000 manufacturing positions since January 2010 — a small fraction of the nearly six million lost between 2000 and 2009. That’s a slower rate of recovery than for nonmanufacturing employment. “We find very little real evidence of a renaissance in U.S. manufacturing activity,” a recent Morgan Stanley report stated, echoing similar findings from Goldman Sachs.

If anything, the challenges to American manufacturing have grown, as less developed countries have become more adept. In Mexico, where each autoworker earned $7.80 per hour in 2012, auto industry officials say productivity is as high as in the United States, where total compensation costs were $45.34 per hour. No surprise then that in 2013, Mexican automobile production was 50 percent higher than seven years earlier, while output in the United States was at the same 2006 levels.

For the United States to remain competitive against countries like Mexico, productivity must continue to rise. But unlike past gains in productivity, these improvements in efficiency are not being passed along to workers.

And these necessary productivity gains often take the place of hiring more workers; the United States remains the world leader in agriculture while employing less than 2 percent of Americans.

Advanced manufacturing — a sector that many advocate as a path for the United States to remain relevant at making things — also involves a high degree of efficiency, meaning not as many hires and particularly, not as many of those old-fashioned, middle-class, assemble-a-thousand-pieces jobs.

Moreover, the lead that the United States has in some advanced manufacturing areas — notably aerospace — is being compromised by growing capabilities of workers elsewhere. Bombardier is now assembling Learjets in Mexico, and later this year Cessna will start delivering Citation XLS+ business jets that were put together in China.

Similarly, while America’s energy boom will provide an incentive for manufacturers to locate here, don’t count on cheap natural gas to fuel an employment boom. According to a 2009 study, only one-tenth of American manufacturing involved significant energy costs.

While we shouldn’t expect manufacturing to save our economy, we needn’t despair. Among other things, we need to get over the notion that service jobs are invariably inferior. The United States remains a world leader in service industries like education and medicine. Not only do these fields generate well-paying jobs, but they also help with our balance of trade: when foreigners come to America to be educated or treated, those services are tallied as exports.

Manufacturing has been an emotional American touchstone since George Washington wore a wool suit that had been woven in Hartford, Conn., to his first inauguration to illustrate the importance of making stuff at home. We do need to maintain an industrial presence, but perhaps not for the obvious reasons.

For one thing, companies often locate research and development facilities — stuffed with high-paying jobs — near their manufacturing facilities. In addition to jobs, R&D yields high-value intellectual property that spills over into still more innovation and employment. And not surprisingly, every manufacturing position requires an additional 4.6 service and supplier positions to support it.

The challenge for the United States is particularly acute because manufacturing now accounts for just 12 percent of our economy, down from a peak of 28 percent in 1953 and on a par with France and Britain as the least industrialized of major economies.

While keeping that share from dipping further should be a priority, we should be careful to avoid raising false hopes (like Mr. Obama’s unrealistic second-term goal of creating a million manufacturing jobs) and pursuing ill-conceived policies (such as special subsidies for manufacturing).

The president’s proposals — unveiled over the last several years — include the two most important elements of a sensible manufacturing strategy: more training focused on the skills needed by employers and increased spending on research and development.

The United States work force is simultaneously overqualified (15 percent of taxi drivers are college graduates) and underqualified (we rank in the bottom half of many comparisons of developed countries).

When Volkswagen arrived in Chattanooga, it found that not enough eager applicants had the requisite technical skills, so it established a German-style training system (including three-year apprenticeships) at the factory.

As for research and development, the fiscal tightening by the federal government has prevented more investment in this critical area, the exact opposite of what is required. At the same time, while subsidies to draw jobs have become a necessary evil, we should be rigorous about analyzing the value of these costs. And we must stop short of excessive meddling in the private sector, and particularly the notion of picking winners. (Think Solyndra or Fisker.)

Mr. Obama skirted this problem by proposing to create 45 “manufacturing innovation institutes,” which bring together companies, universities and government experts in a kind of laboratory setting to help develop advanced manufacturing strategies.

While these institutes are not going to turn the tide, they might help at the margin. But like the president’s other proposals, they have been largely ignored by Congress. (The White House managed to establish a pilot center in Youngstown, Ohio, and another is coming in Charlotte, N.C.)

Manufacturing would benefit from the same reforms that would help the broader economy: restructuring of our loophole-ridden corporate tax code, new policies to bring in skilled immigrants, added spending on infrastructure and, yes, more trade agreements to encourage foreign direct investment and help get closer to Mr. Obama’s seemingly unattainable goal of doubling our exports.

Those who see a brighter manufacturing picture for the United States argue that wages are rising more rapidly elsewhere, not just in China and Brazil but also in Japan, Germany and France. But just like the “feel good” stories, celebrating this fact ignores the reality that the flip side of wages’ rising faster elsewhere means they are rising more slowly here.

And that is the essence of our challenge: In a flattened world, there will always be another China.