Originally published in The New York Times.

The Treasury Department reported last month that the nation closed its fiscal year with the national debt having reached a record $31 trillion, a stunning rise from a comparatively modest $20 trillion just six years earlier.

The announcement elicited little notice. Given the rate at which our obligations are now rising, that’s most unfortunate.

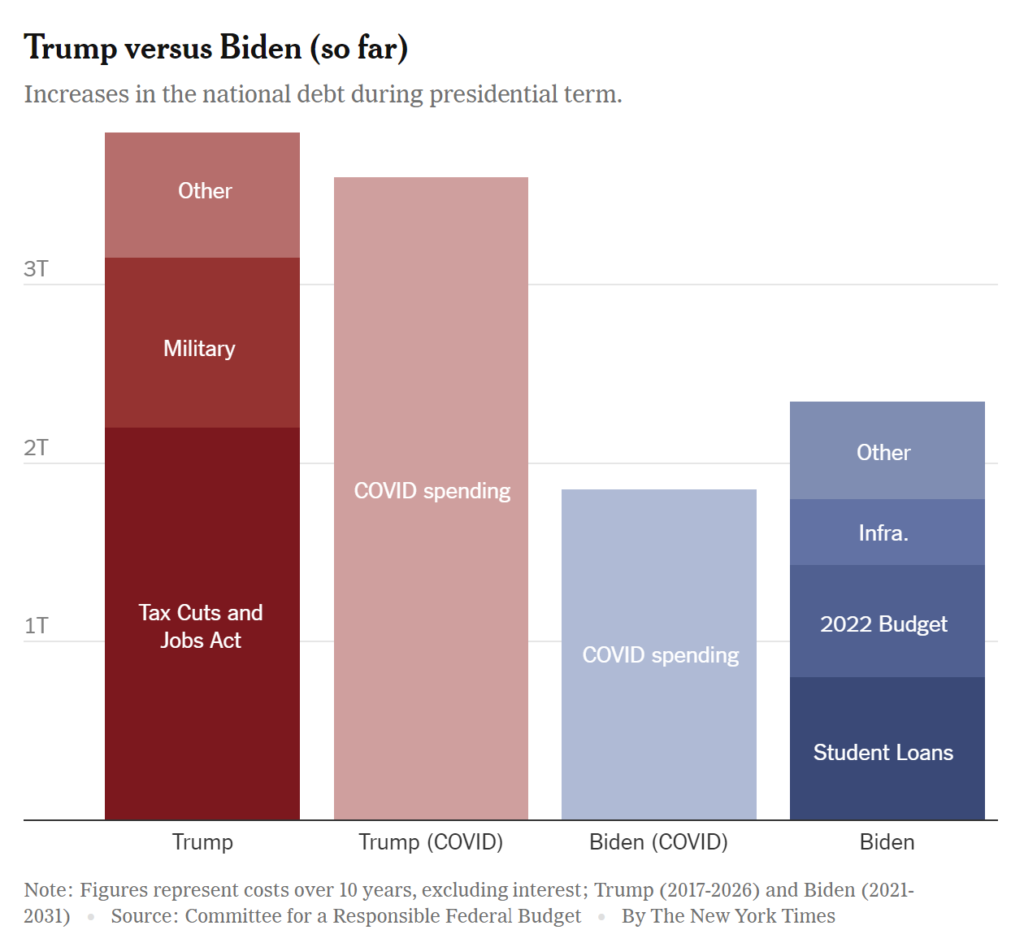

For sure, the huge costs incurred in minimizing the effects of Covid played a major role in this debt explosion, but the poorest fiscal policy in at least a half-century — courtesy of two presidents, a Republican and a Democrat — played an even bigger part and add to the urgency of addressing this problem.

While President Biden is approaching only the halfway mark in his term, the four-year record of the Republicans — the party that most often lectures the nation about fiscal rectitude — is likely to end up being even worse than that of the Democrats. After the spending spree of the past nearly three years, the appetite for more big unfunded spending packages has fortunately diminished, at least for the moment. The Republicans, conveniently resuming their commitment to fiscal responsibility just as they may be about to take power in Congress, are threatening to leverage a debt crisis to force through spending cuts — all while simultaneously aiming to extend Trump-era tax cuts.

But the abandonment of fiscal restraint began under Republican leadership. President George W. Bush pursued both tax cuts and substantial spending increases (like the unfunded prescription drug plan) with considerable vigor. A remark reportedly by Vice President Dick Cheney provided justification: “Reagan proved deficits don’t matter.”

Whatever Mr. Bush’s sins, President Donald Trump took fiscal irresponsibility to a new level. He arrived thumping the tax-cut drum, and his Republican-controlled Congress quickly enacted a $1.9 trillion tax cut that delivered 84 percent of its benefits to Americans earning more than $86,000 per year.

To manage the budget deficit, cutting taxes — however unfairly it was done — should have led to restraint on the spending side. Instead, Republicans took the opposite approach. Federal outlays rose by $127 billion in the 2018 fiscal year (a 3.2 percent increase) and by a whopping $338 billion the following year (an 8.2 percent jump). By comparison, inflation ran at about a 2 percent annual rate in those years.

On a 10-year basis, nearly $1 trillion was allocated for expanded military spending, with just $150 billion directed to veterans. And after proposing during the 2016 campaign to cut $750 billion from nonmilitary discretionary spending, Mr. Trump signed into law — with complicity from Democrats — increases in this category that did almost exactly the opposite of what he promised: Instead of the promised cut, we got $700 billion more spending.

Not surprisingly, all of that nearly doubled the deficit, from $585 billion in the last full fiscal year before Mr. Trump’s arrival to the nearly $1 trillion expected for 2020 before Covid hit.

And then the virus arrived. Under Mr. Trump, several rounds of Covid relief measures — pushed by both parties — loaded a necessary $3.4 trillion in fresh outlays onto a fiscal regime that was poorly prepared to withstand them. The deficit in 2020 alone reached $3.1 trillion.

Mr. Biden took office determined to add to the Covid-fighting measures while pursuing a flotilla of domestic objectives through two other packages that would have brought $4.5 trillion in new outlays and added $1.2 trillion to the debt. A more targeted approach, focused on priorities like addressing climate change and encouraging investment, would have been far better.

His $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, passed along a party-line vote, shoveled more stimulus checks to Americans who had much of the earlier stimulus checks still in their bank accounts. It also unnecessarily showered money on other Democratic favorites, like state and local governments, many of which ended up running substantial financial surpluses. The budgetary gap in 2021 reached $2.8 trillion.

All of that deficit spending not only pushed up the national debt but also helped trigger the inflation that has now become the nation’s bête noire.

Still more debt is to come from Mr. Biden’s ill-conceived student loan forgiveness plan, which the Congressional Budget Office recently gauged as costing about $400 billion over the next 30 years. And that doesn’t include a second piece of Mr. Biden’s student loan package, a proposal that would limit borrowers’ future payments to a lower fixed percentage of their incomes, potentially adding another $120 billion of costs.

Meanwhile, Congress passed other meritorious legislation to encourage domestic semiconductor production, aid veterans and rebuild crumbling infrastructure, none of which was matched by offsetting tax increases.

For years, progressive advocates of more federal spending (and more deficits) had argued that with borrowing costs low, Washington could afford to spend more in areas like infrastructure without pushing the deficit substantially higher.

But now the government’s 10-year borrowing cost has gone from a prepandemic 1.5 percent to 4 percent. With that has come a substantial increase in interest costs. The C.B.O. projects that the interest expense will increase to 7.2 percent of gross domestic product by 2052 from 1.6 percent this year.

Except during the 2008 financial crisis, the United States had never run a $1 trillion deficit — until Mr. Trump arrived. Current official projections show that without action, deficits will remain above $1 trillion indefinitely.

That puts the federal debt on track to reach $45 trillion in a decade. A vibrant economy can manage substantial amounts of debt incurred to finance important national goals. But a nation in which debt is growing faster than the economy will eventually be brought to its knees.