Perhaps we should have seen this coming.

In his first term, Donald Trump was not shy about using the bully pulpit of the presidency to attack any institution that interfered with his uniquely distorted economic philosophy. He roundly criticized the chairman of the Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell, for raising interest rates. He harangued Harley-Davidson for moving production and jobs offshore to avoid the effects of his trade war. He threatened Boeing over cost overruns in building new Air Force Ones and gave America a preview of his weaponized tariffs.

Those skirmishes pale in comparison to the interference and even extortion of Trump 2.0., a set of actions that at times bear resemblance to China’s state-directed capitalism.

Mr. Trump is muscling his way into our economy in ways that are alien to traditional Republican principles, alien even to what more interventionist Democrats have argued for, and wildly at odds with any sensible notion of how the relationship between government and business should be managed.

Most dramatically, he is now attempting to fire a member of the Fed’s Board of Governors, Lisa Cook, an action of dubious legality that could have seriously negative consequences for our economy. Just days ago he forced Intel, the struggling semiconductor company, to give the U.S. government a nearly 10 percent stake in the company in return for grants it had received in the Biden administration. (That was after demanding the resignation of Intel’s chief executive earlier this month and then changing his mind a few days later.)

I don’t know of any case, at least in my lifetime, of the government taking equity in a company simply because it could. Add these to the long list of ways that Mr. Trump is undermining the rule of law, one of the most important principles that undergirds our economic success.

When it comes to the private sector, the government certainly has an important role. Prudent regulation and tax policy are central to curbing the potential excesses of capitalism. When we are lagging in a critical industrial sector with national security implications, as we are in semiconductor manufacturing, legislation like the CHIPS and Science Act, which aimed to strengthen America’s semiconductor industry by providing billions in subsidies, can play a helpful role.

When markets fail, as they did during the financial crisis, Washington should bridge that gap.

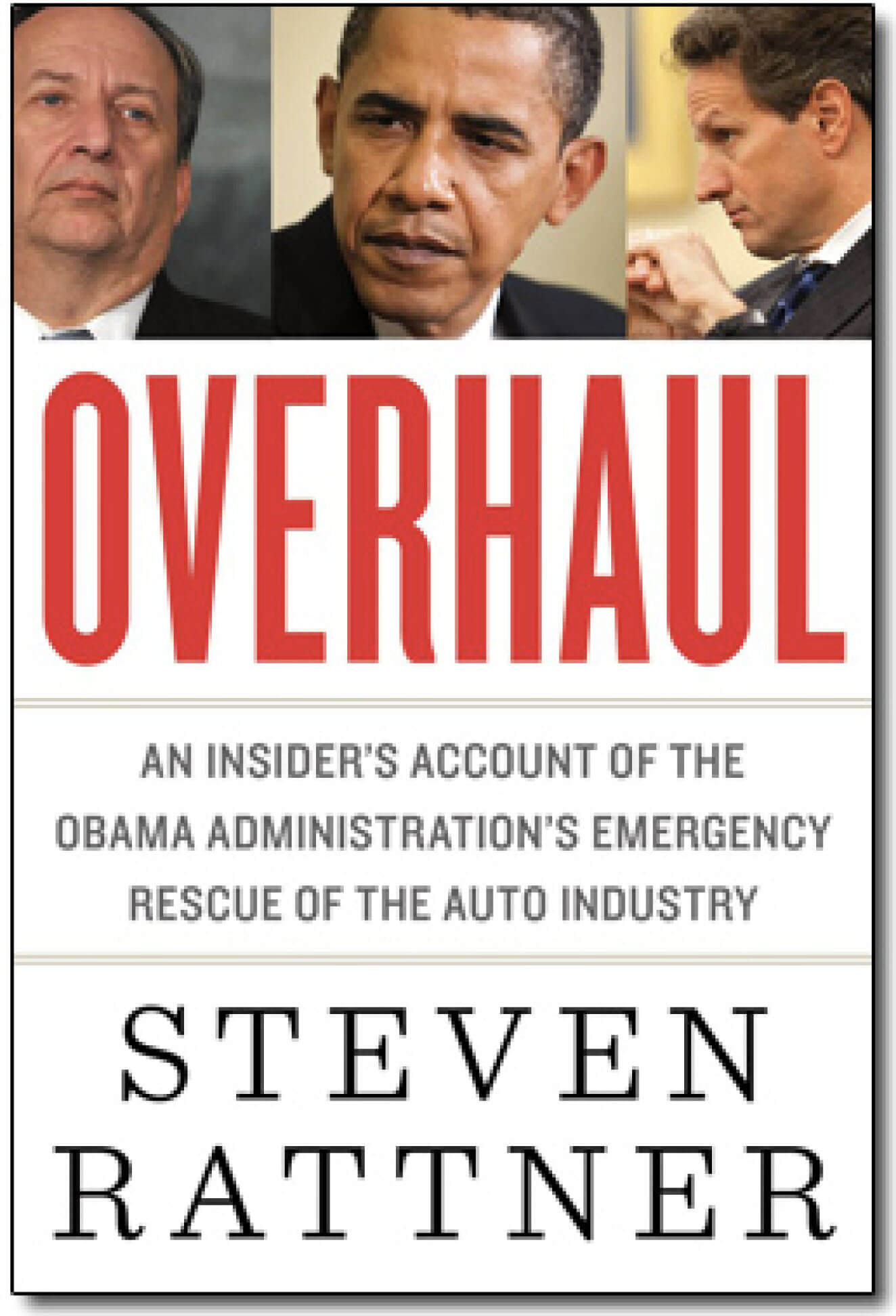

In early 2009, as Barack Obama assumed the presidency, the automobile industry was on the verge of disaster (in contrast to today’s more benign conditions). I was asked by that administration to lead an auto task force with clear instructions to approach the problem as we would any commercial investment — but with a bias toward saving these iconic companies at a time when the economy appeared to be in free fall.

Over the ensuing months, the 14-member task force, mostly with private sector experience, conducted the due diligence and performed the analyses we had been trained to do in the private sector, which we regularly presented to Mr. Obama and his aides. Our recommendations were thoroughly debated within the most senior circles of the White House before the president made the final decisions in March. By summer, the companies had been restructured through the bankruptcy process and emerged smaller, leaner and largely shorn of debt.

And even though the government received a majority interest in the automaker in return for nearly $50 billion in assistance, we took no board seats or any special rights. “Our goal was to get G.M. back on its feet, maintain a hands-off approach and get out quickly,” Mr. Obama said at the time. That allowed the company to focus successfully on its core mission of selling cars and making a profit. Then the government fully divested its ownership interest.

That approach — only stepping in during a crisis and minimizing the government’s involvement — stands in stark contrast to the way Mr. Trump is managing his interventions. His shoot-from-the-hip style lurches from one extreme to another, deploying the government’s power in extraordinary ways that diminish the predictability and order that business craves from Washington.

His capriciousness is particularly visible in the semiconductor industry. In addition to his Intel invasion — a permanent stake rather than the temporary ownership we took in G.M. — Mr. Trump has also been busy burrowing into Nvidia, the world’s largest semiconductor company, whose chips are critical to the artificial intelligence boom. In April, Mr. Trump essentially banned Nvidia from exporting its H20 chips to China, only to relax those rules after the company agreed to turn over 15 percent of those revenues to the government. (That may well prove to violate the constitutional ban on taxing exports.)

Along similar lines, Mr. Trump didn’t allow Nippon Steel’s proposed acquisition of U.S. Steel to go through until the government was granted a “golden share” giving Washington a veto over a broad array of corporate actions, including employee salaries and changing the company’s name.

Meanwhile, the repeal of key provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act pushed by Mr. Trump has already resulted in the cancellation of new projects in the automobile electrification ecosystem. His tariffs are costing those companies dearly — G.M. recently said that the tariffs would slice $4 billion to $5 billion from its profits this year; Ford estimates its profits would be hit by $2 billion.

Trade has been Mr. Trump’s favorite playground for his version of industrial policy, with tariffs being a weapon of choice. He has compared the United States to a “giant department store,” with him as the manager. “I own the store and I set the prices, and I’ll say, ‘If you want to shop here, this is what you have to pay,’” he told Time magazine in April.

According to Axios, the White House has created a scorecard that rated 553 companies and trade associations based on their support for Mr. Trump’s signature tax and spending package, suggesting that companies that were insufficiently supportive could suffer retribution.

All of that can reasonably be called extortion.