In the past, the one constituency President Trump has sometimes listened to has been our stock market. Well, it has spoken, falling 10.5 percent in one of the largest two-day stock market swoons in decades.

In the 50 years I have been immersed in markets and economic policy, I have never before witnessed a signature economic policy initiative that was met with such unalloyed criticism. What’s worse, the damage was entirely self-inflicted.

Why such a reaction? One reason the S&P 500 fell was that the tariffs Mr. Trump rolled out were so much greater than investors anticipated. (Give the White House an F for failing to prepare the market for what to expect.) Then on Friday, China announced its own 34 percent tariff on our goods, making it clear that our trading partners were not going to simply give in to Mr. Trump’s demands, as he had suggested they would.

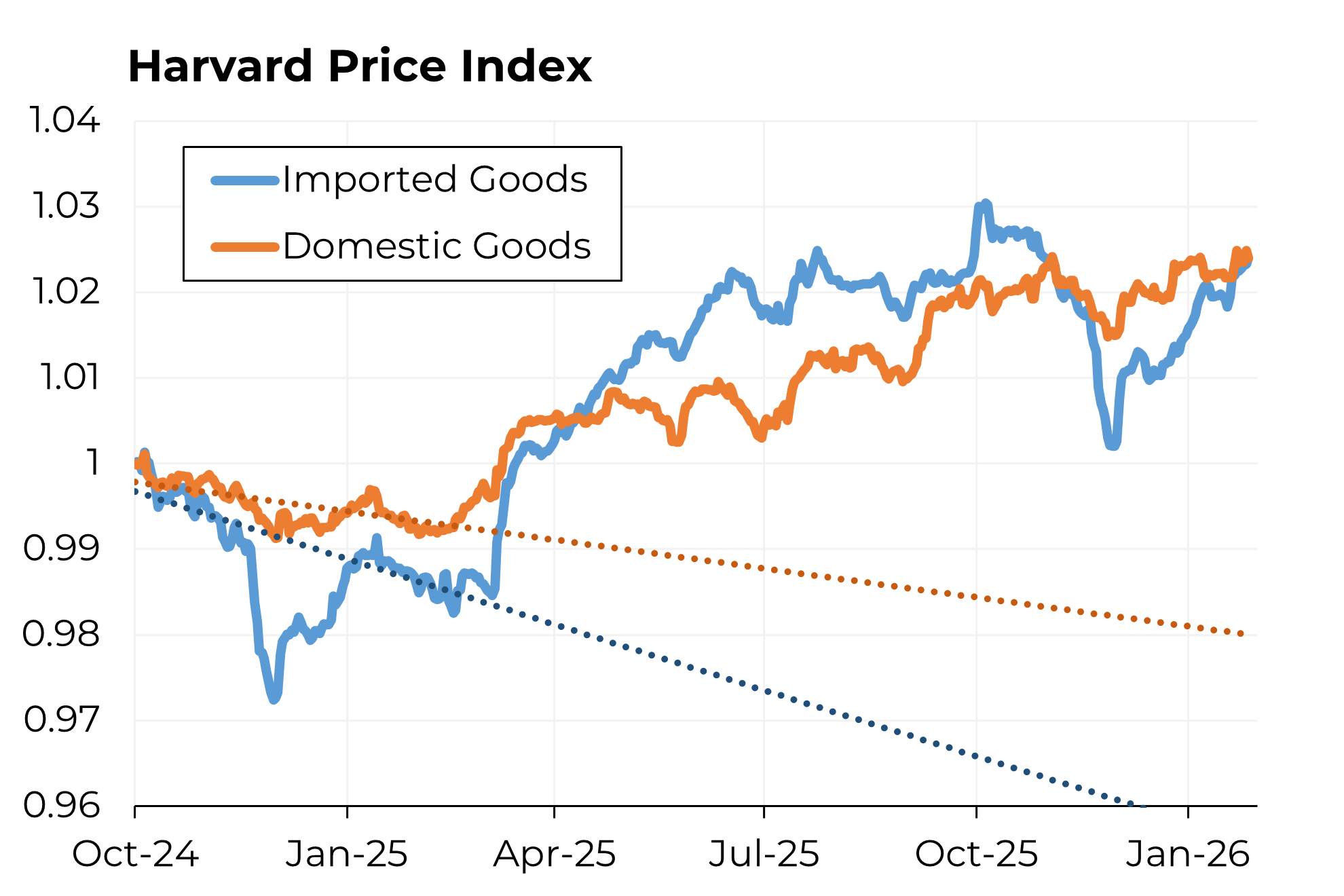

As Mr. Trump was doubling down, asserting that “my policies will never change,” the Federal Reserve chairman, Jerome Powell, was delivering his own bombshell: Given the higher-than-predicted tariffs, higher inflation and slower growth were likely to ensue, he said. That’s drastically different from just a couple of weeks ago, when Mr. Powell called the potential impact of new tariffs on prices “transitory.”

The business community, which by my count heavily supported Mr. Trump in the election five months ago, seems stunned. Few have spoken publicly, but the Business Roundtable, the premier corporate trade association, on Wednesday warned that universal tariffs run “the risk of causing major harm to American manufacturers, workers, families and exporters.”

Privately, several chief executives told me that they recognized that imposing the tariffs, as well as Mr. Trump’s intractable support of them, was a potentially cataclysmic mistake. “Few of us ever imagined he would go this far,” one told me. “He could well bring down the economy and himself.”

The Trump-supporting business leaders I’ve spoken to in the last two days don’t yet regret their votes, mostly because of their intense distaste (if not hatred) for the Biden-Harris administration. And they remain broadly supportive of the efforts by the tech billionaire Elon Musk to reform the federal government, even if they acknowledge that his DOGE team may be going too far in its slashing of spending and personnel.

But I wonder how some other major Trump-supporting leaders whose stock prices have been particularly hard hit now feel, like Stephen Schwarzman, chief executive of Blackstone, the investment group (down 15 percent in two days), and Safra Catz, chief executive of Oracle, the database company (down 12 percent).

Mr. Trump’s actions aren’t the only problem. Almost as important is the lack of clarity as to what policies he is pursuing and why. At times, Mr. Trump implies that the purpose of the tariffs is to bring back manufacturing, which suggests that they will stay in place indefinitely. At other times, he suggests that the goal is to negotiate tariff reductions by other countries (even though much of what Mr. Trump asserts about their tariffs is inaccurate).

The dithering takes a real toll. I see this from my role as a professional investor. How do we evaluate a company that imports goods or engages in international commerce? We seek a lower price, or we grit our teeth, or we pass on the opportunity. As a result, our pace of investing has slowed sharply this year.

And it’s not just us. In the year’s first quarter, the number of newly announced mergers and acquisitions dropped to its lowest level since the financial crisis. “Folks are looking but not pulling the trigger,” one leading investment banker told me. Equity offerings have become similarly challenged; multiple companies planning to go public have postponed their fund-raising since Wednesday.

Even experts inside the Trump bubble are flummoxed. In a recent private call with investors, one senior official in the first Trump administration confidently predicted that autos coming from Mexico would get more favorable treatment than those originating in Canada. The following day, Mr. Trump imposed the same duties on vehicles coming from the two countries.

The outlook is bleak. Prediction markets put the odds of a recession at 50 percent or even a bit higher. And while the jobs figures that were released Friday were sound, the Conference Board recently reported that consumer expectations for the economy hit their lowest level in 12 years, while anticipated inflation over the next year (measured before the tariff announcement) has jumped to 6.2 percent. Domestic manufacturing production is now contracting. Stagflation — that particularly painful combination of inflation and economic stagnation — has become the least harm that we are likely to experience.

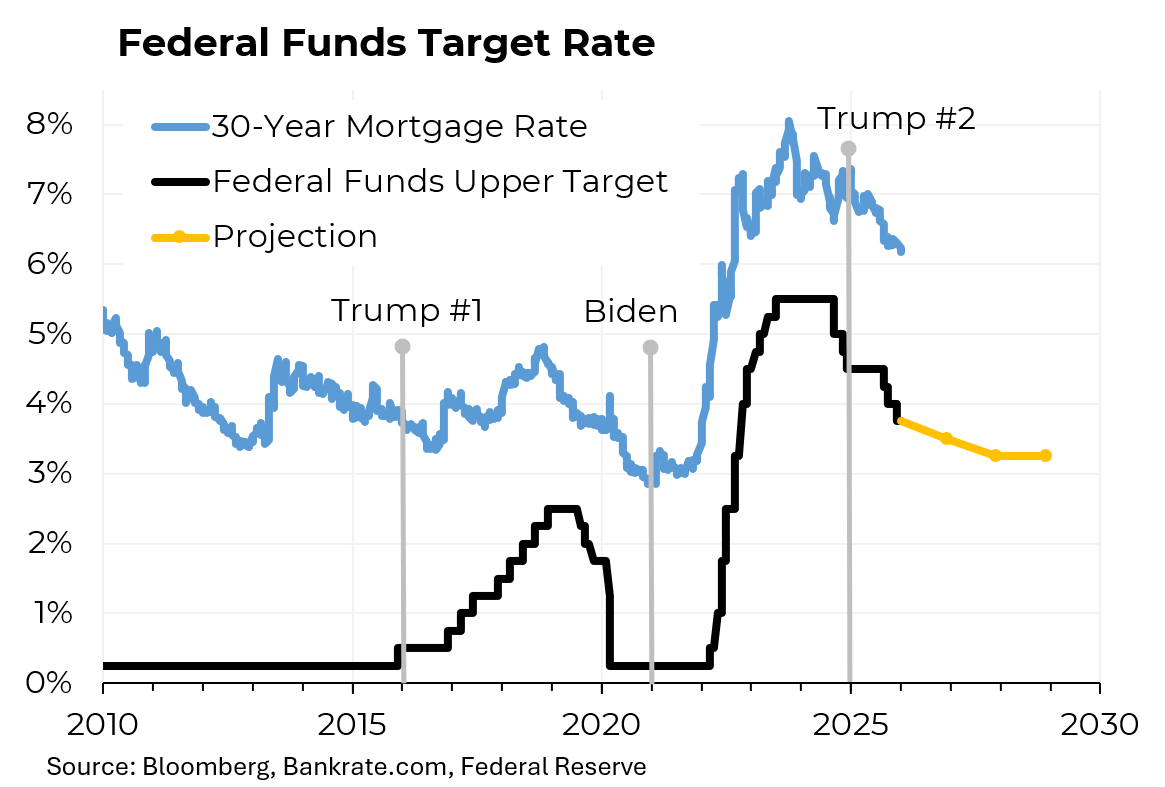

In a normal world, when an economy falters, eyes turn to the central bank for help, in the form of reductions in interest rates. But progress on inflation has stalled, making it more difficult for the Fed to come to the rescue. And the new tariffs will only make inflation worse.

Many business people and investors are still hoping Mr. Trump will recognize the havoc he is creating and ease off his tariffs. But so far, he doesn’t seem concerned. And that may be our biggest worry of all.