Sometimes, swift and forceful government intervention in the private sector is the only way out of a crisis

Originally appeared in the New York Times.

Almost exactly 10 years ago, President Barack Obama went before the nation to unveil an urgent overhaul of the nation’s automobile industry.

The financial crisis and plummeting economy had swept America’s already fragile carmakers into an existential crisis. Unaided, a complete collapse of the sector, including its many suppliers and dealers, was inevitable. At Mr. Obama’s instruction, the auto task force, which I led, administered a strong dose of tough medicine.

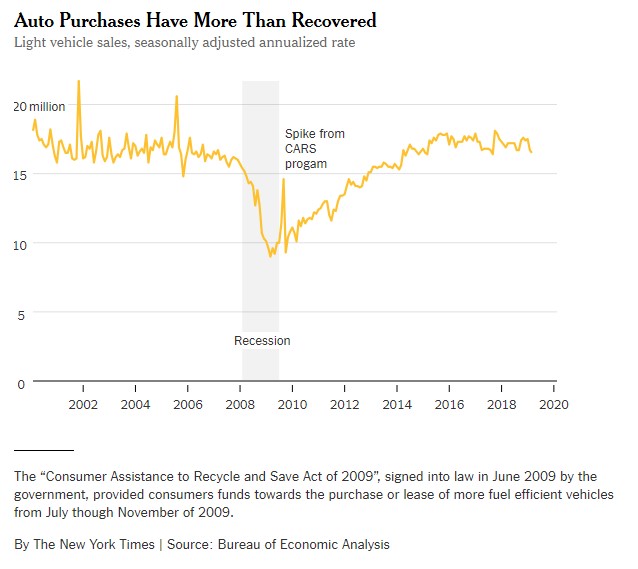

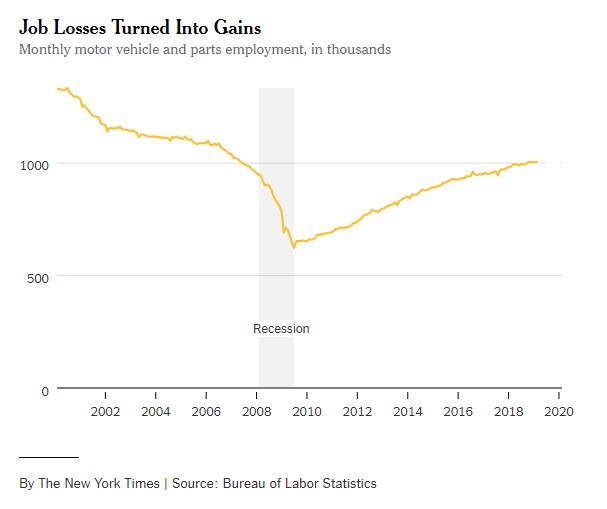

The ensuing turnaround was remarkable. Vehicle sales, which had fallen nearly in half, bounded back, reaching an 18 million pace in late 2017. Massive losses became massive profits. Employment across the sector, which had fallen to 623,000, has grown to a million Americans.

In acting so muscularly, Mr. Obama defied both conservative critics and public sentiment. A poll in October 2009 showed that 54 percent of Americans opposed government help for the industry.

That, too, has flipped. By 2012, 56 percent of Americans supported the help given to the car companies. And little has been heard from the loud voices that denounced Mr. Obama for reaching forcefully into the private sector.

While we didn’t get everything right, I came away from the job with some pre-existing views reinforced and some new lessons learned:

Lesson One: As successful as our private enterprise system has been, the auto crisis and, for that matter, the entire financial crisis reminded me that government has an important role to play in overseeing business.

In normal times, capitalism needs supervision to ensure that companies compete fairly, don’t take advantage of workers and produce safe products, to name just a few examples. In extraordinary times, such as when markets fail, government can prudently step in with salutary effects.

That was the case in 2009. Without help from Washington, the collapse in auto sales would have exhausted General Motors’s and Chrysler’s cash reserves, forcing them to close their doors, lay off all their workers and liquidate.

The collateral damage would have been vast; perhaps a million Americans would have lost their jobs, at least in the short run, at a time when unemployment was already nearing 10 percent. Our critics said we should let private capital handle it. But in those terrifying days, not a penny of private money would have been made available to the auto sector.

Lesson Two: Saving American companies is not necessarily the same thing as saving American jobs. Yes, domestic employment in the auto sector has recovered nicely. But the number of Mexican autoworkers has grown even faster.

That’s because workers in Mexico and elsewhere have become more productive while wages have stayed relatively low. Pressure remains on auto companies, with their persistently low margins, to shift jobs offshore.

Lesson Three: Our system of government does not make speedy, effective interventions of this sort easy. In providing capital to the auto sector, we were lucky to have access to the $700 billion fund passed by Congress to rescue the financial system, and so was the George W. Bush administration, which wisely provided emergency bridge loans in December 2008.

Without that, I am convinced that the failure of at least one major auto company would have had been required to get Congress to act expeditiously. In 1979, when Chrysler previously requested emergency aid, it took five months for Congress to approve $1.5 billion in rescue loans and an additional six months for Chrysler to meet the numerous conditions that Congress imposed before the company could receive its first tranche of funds.

Lesson Four: Solving an existential crisis is best done without political pressure. Even under truth serum, I would affirm the president’s decision to insulate our team from the lobbying of innumerable special interests, some of which had been major supporters during his election campaign just a few months earlier.

Lesson Five: Management matters. Why did General Motors and Chrysler almost vaporize while Ford, although struggling, never needed help from the auto task force? Largely because Ford had better leadership that had anticipated the downturn and prepared for it.

In my 35 years working with companies, I have repeatedly been struck by the transformational impact that a single individual can have on a business, even on a massive multinational corporation with hundreds of thousands of employees.

Happily, governance at General Motors is much improved, and in Mary Barra, the company has a first-rate chief executive.

Lesson Six: Success can be transitory. Today, it is Ford that is struggling. And all automakers are facing profound changes, some of which were not even a glimmer on the horizon in 2009. During my time at the Treasury Department, we heard a bit about electric cars, but to my recollection, the words “autonomous driving” and “ride sharing” were never uttered.

Far from its ostrichlike behavior in the years before the rescue, the American auto industry appears to have taken this lesson to heart, particularly in prescient moves like General Motors’ decision to move early into self-driving car technology.

For the sake of all Americans, let’s hope that the lessons of the industry’s near-death experience a decade ago remain fresh.