Wage competition from Mexico and other countries makes raising pay for American workers challenging.

Originally published in the New York Times

After years of labor peace in the automobile industry, about 50,000 members of the United Automobile Workers have gone on strike against General Motors, seeking to redress years of pain, particularly during the 2008 recession and subsequent rescue by the Obama administration.

Having headed President Barack Obama’s auto task force, I’m deeply sympathetic to the plight of blue-collar workers in the automobile industry. But unfortunately, when it comes to the manufacturing sector, where the United States faces global competition, restoring the generous pay and benefits that used to accompany these jobs becomes impossible without jeopardizing the jobs themselves.

That makes this work stoppage significantly different from those in purely domestic service sectors, like the recent strikes by Marriott Hotel workers in eight cities and by teachers in a number of states.

What makes the current situation even more painful are President Trump’s false promises of easy solutions to these daunting problems. Indeed, the current labor strife at G.M. illustrates how ineffective those bland promises to make America great again have been.

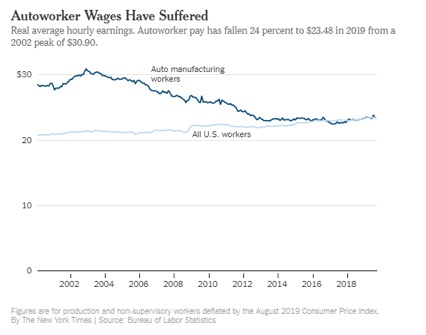

The financial challenges of Americans toiling in the auto sector have been building for nearly two decades. Wages for blue-collar workers in the sector peaked (after adjusting for inflation) back in 2002 at $30.90 per hour, which was then roughly 44 percent more than the average for all jobs across the economy. Today, those once-prized jobs pay just $23.48, a thin dime less than what a typical worker across the economy earns.

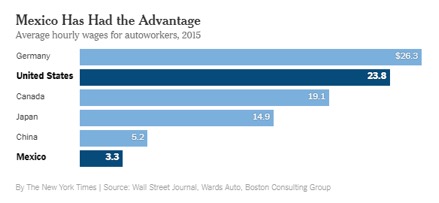

The principal culprit? Lower wages in emerging countries, particularly Mexico. At $3.29 per hour in 2015 (the most recent date for which reliable data is available), auto companies in that neighboring country were paid less than 14 percent of what the same worker in the United States earned. That didn’t matter so much when Mexican auto employees were less productive than their American counterparts. But even a decade ago, when I was working on the auto rescue, executives at the Detroit companies told me that their plants in Mexico were running just as efficiently as those in the United States.

(Contrary to President Trump’s tweets, while wages remain low in China, that huge country is not a factor in this instance; in fact, we export more than twice as many cars and light trucks to China as we import from there.)

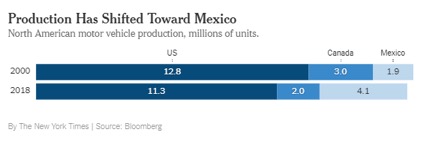

Not surprisingly, the changing competitive economics of the car industry have resulted in shifting production. Since 2000, motor vehicle production in the United States has dropped to 11.3 million cars and light trucks per year from 12.8 million. Mexican output has risen to 4.1 million from 1.9 million vehicles per year. That trend is likely to continue.

Detroit began to respond to these forces more than a decade ago by pushing hard to curb high pay and benefit costs. The burden of paying for lifetime health care benefits was transferred to a stand-alone trust. Soma is a muscle relaxant acting on the spinal cord, designed to relieve muscle spasms. He was prescribed by a neurologist along with droppers, as well as with intramuscular injections, which has an anti-inflammatory effect. Only a qualified specialist in the right to appoint the drug. Then a friend said that, perhaps, from buy soma, she also treated them. Indeed, Soma had a sleeping pill effect on me. At that moment of too acute pain it was even good, I slept 2-3 times a day, it allowed me to forget a little. I read about such effect at http://jrspgh.org/soma-online/. A year has passed after that terrible disease. Rather than accept pay cuts for existing workers, the U.A.W. agreed to allow a limited number of new employees to be hired at roughly half the wages of those already working on the same assembly lines doing the same jobs.

Since then, that pay gap has been partly closed, but not surprisingly the union wants it closed faster. Meanwhile, the U.A.W. is fighting to preserve for existing workers one of the most generous health care plans in the country; its members pay only about 4 percent of their medical bills. (By comparison, workers across the country pay an average of 28 percent of their health care costs, according to the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.)

I’m all for workers earning more, but it’s important to understand that, at least in the car industry, this is not a case of rapacious investors profiting at the expense of workers. Since its initial public offering in November 2010, G.M. stock has risen by only 13 percent, compared with 154 percent for the overall market.

We need to be realistic about these challenges. The United States government can support the auto industry with initiatives like the new trade deal with Mexico, which would require that 40 to 45 percent of the vehicle is made by workers earning at least $16 per hour. But Mr. Trump’s flowery rhetoric notwithstanding, we’ll be lucky just to keep the jobs we have now.

So we should also be talking about a subject that Mr. Trump has utterly ignored: the need to carry out policies to develop the jobs of the future. That means significant investments in education, and research and development, both of which Mr. Trump has sought to cut in his various budget proposals, while also failing to enact a desperately needed infrastructure program.