Originally published in the New York Times

ONE sure sign that federal regulations and policies are out of whack is when companies start making a business model out of gaming them. That’s particularly true in two areas of government rule making — drug regulation and corporate taxes.

Consider the success of Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

Just four years ago, this little-known company was struggling: its share price was measured in pennies, and Jazz had missed a string of interest payments on its debt. Today, its stock has levitated to $68 per share.

Jazz accomplished that $4 billion enrichment of its shareholders thanks to well-intentioned federal regulations that deterred competition for its principal product, compliant health insurers, and a Swiss-cheese corporate tax regime.

Don’t get me wrong: Jazz’s mainstay, Xyrem, which is currently used by about 10,500 Americans, is a good drug. While it doesn’t cure any deadly disease or even directly prolong life, it does help those with narcolepsy, a debilitating ailment that causes people to fall asleep unexpectedly during the day, and a related condition, cataplexy.

Xyrem came to Jazz as the centerpiece of its acquisition of Orphan Medical, so named because of its focus on orphan drugs — those intended to treat uncommon disorders (affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the United States) that are ignored by many big pharmaceutical companies.

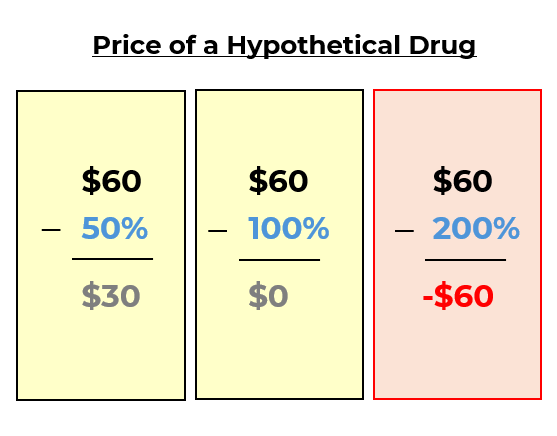

To get drug developers to focus on these relatively small pools of patients, the federal government offers inducements like a 50 percent research-and-development tax credit as well as a longer period of market exclusivity (seven years after Food and Drug Administration approval, rather than the typical five). These long monopolies often give orphan drug makers a free hand to raise prices.

That’s precisely what Jazz has done, often multiple times each year, at an average annual rate of nearly 40 percent. Today, Xyrem costs more than $65,000 per year for the typical user.

The drug will account for approximately $550 million in revenue this year, making up a majority of Jazz’s total sales. Last year, Jazz turned 49 cents of every revenue dollar into net profit, an extraordinary margin even for a pharmaceutical company.

The Orphan Drug Act of 1983 was intended to encourage drug makers to invest in treatments for underserved diseases, for which research-and-development costs can often be high and the markets for the medicines too small to make the expenditure worthwhile. But Xyrem, which is a modification of a long-available compound, was inexpensive to develop, as new drugs go. Indeed, Jazz paid only $146 million for Orphan Medical, just a fraction of what it now earns each year from Xyrem alone. (The company contends that it has spent considerably on its development.)

Central to Jazz’s pricing strategy, moreover, has been the willingness of insurance companies to reimburse the cost of Xyrem, even when physicians prescribe the drug for other ailments (like insomnia), as they are permitted to do. Nearly every patient gets the drug pretty cheaply — Jazz subsidizes co-payments above $35 per month — so few users care what Jazz charges.

The corporate tax system, meanwhile, has further sweetened the pot. As profits began to gush, Jazz was able to avoid a heavy United States tax bill by merging with an Irish company that was one-quarter its size and moving to Ireland, where the tax climes are more convivial.

The tax laws didn’t require Jazz’s senior management to decamp; the company’s top four executives are still based in sunny Palo Alto, Calif. And unlike multinationals incorporated in the United States, Jazz can bring unlimited amounts of cash across the Atlantic without paying American tax rates that can reach 40 percent. All told, analysts estimate that Jazz will pay about 18 percent of its earnings in taxes this year.

To be fair, while Jazz’s success in mastering the government’s web of policies and regulations is notable, the company is hardly alone. For example, Questcor has raised the price of a vial of its flagship drug, Acthar, used in the treatment of multiple sclerosis and other ailments, from around $50 in 2001 to $28,000 today. And using tax havens to shield profits is a hallmark of the pharma industry.

As for Jazz, Wall Street remains bullish. Although Xyrem’s orphan status expired at the end of last year, Jazz has erected a small fortress of patents around the product and is actively litigating to defend them. What’s more, the company is now pursuing orphan status for two other drugs.

And hey, why not? When Uncle Sam is willing to play Daddy Warbucks, being an orphan is a smart move.