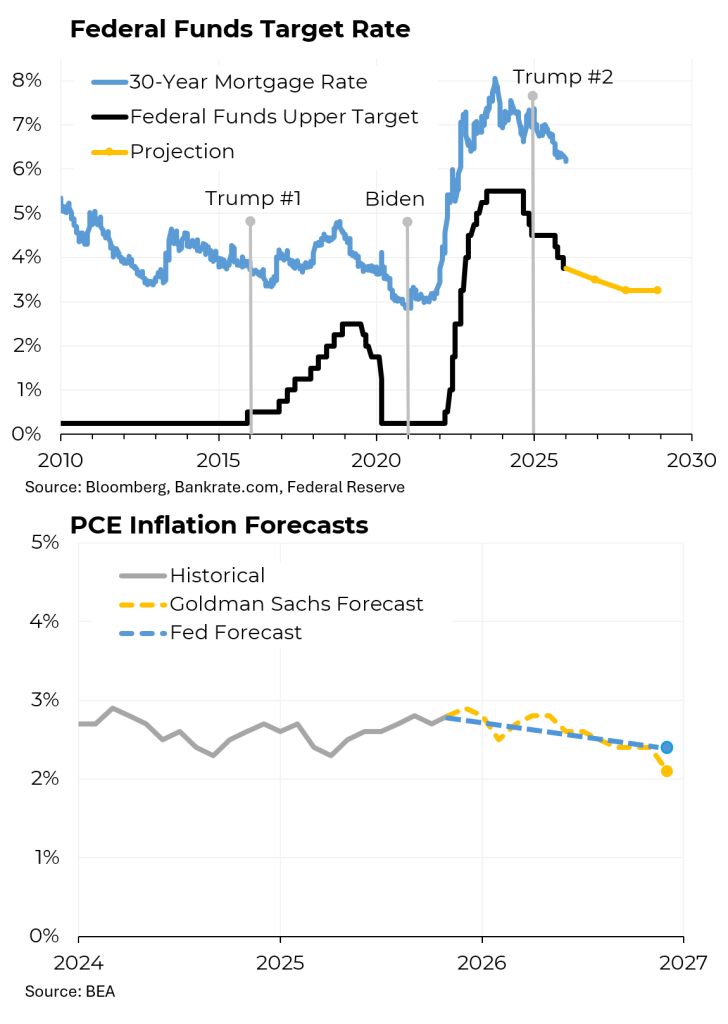

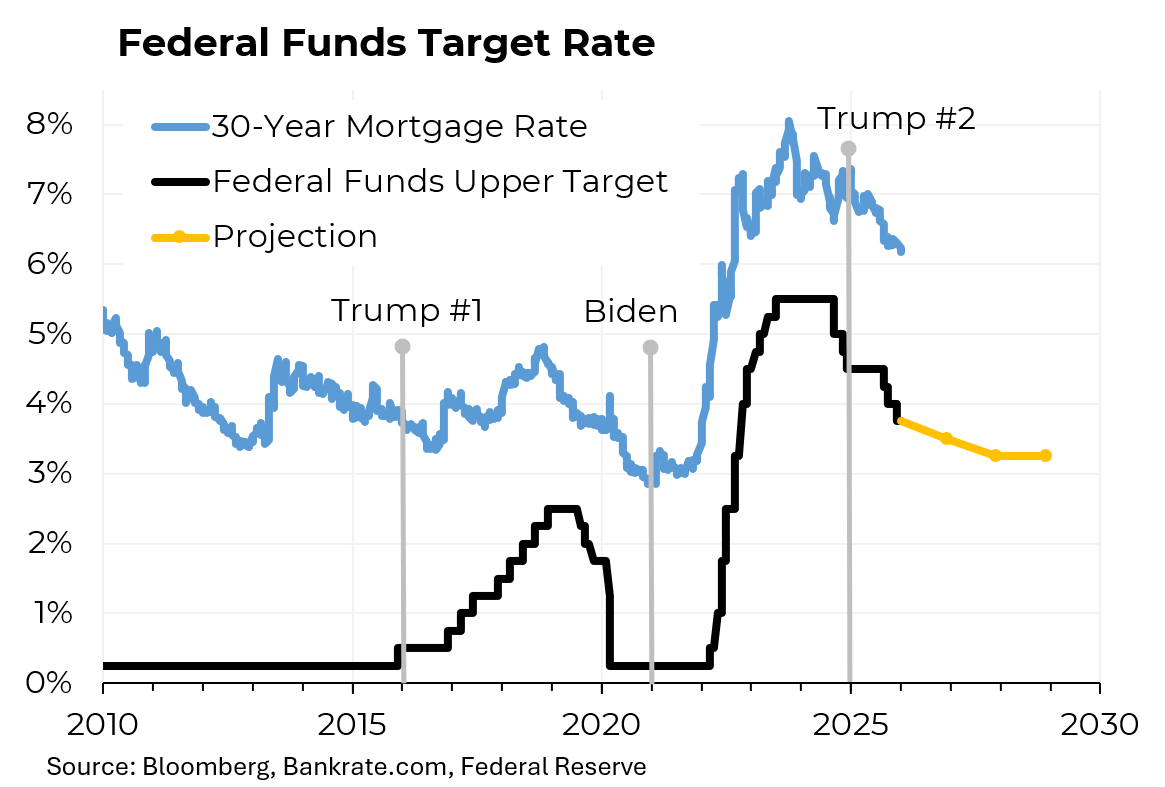

As expected, the Federal Open Market Committee left interest rates unchanged on Wednesday for the first time since July. Two Fed governors, both appointed by Donald Trump, dissented, arguing as Trump has been, that the central bank should continue to lower interest rates.

From a peak of 5.25% to 5.5% that lasted until September 2024, rates have been cut seven times. In recent months, the Fed has signaled that further cuts are likely to be modest: just another 0.25% this year and the same next year. So while the Fed does not directly control mortgage rates, that suggests that those rates are not likely to decline much from their current average of 6.2%, a level that is challenging for many potential home buyers.

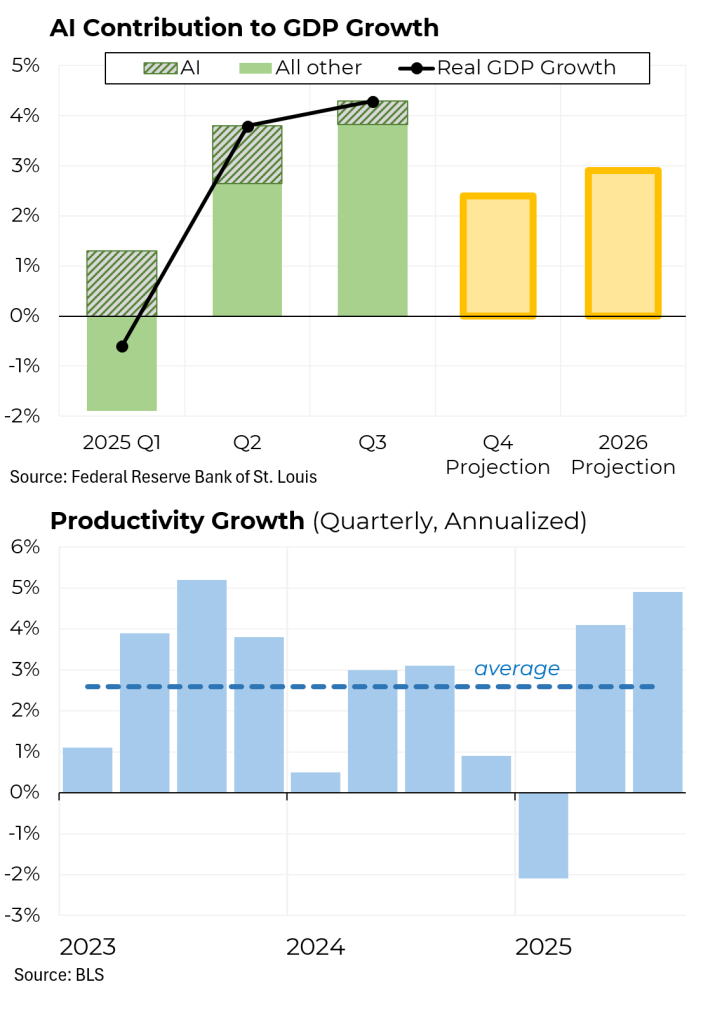

Why did the Fed decide to pause its rate cutting? For one thing, at its current target range of 3.5% to 3.75%, interest rates are close to being what economists call “neutral,” meaning that they are neither stimulating nor retarding economic growth. That is particularly appropriate because inflation has not yet declined to the Fed’s 2% target. Indeed, the FOMC’s own members do not expect inflation to reach its target until at least 2028. (Goldman Sachs is marginally more optimistic; some other private forecasters are more pessimistic.)

Another reason for the Fed’s caution is that economic growth has proven stronger than many expected. In the third quarter, gross domestic product (adjusted for inflation) rose at a 4.3% annual rate, well above the post-Covid trend of between 2% and 3%. And while growth is expected to moderate in the fourth quarter, it is anticipated to be around 3% next year. It’s important to note that a significant component of both recent and anticipated growth has been the boom in spending related to artificial intelligence.

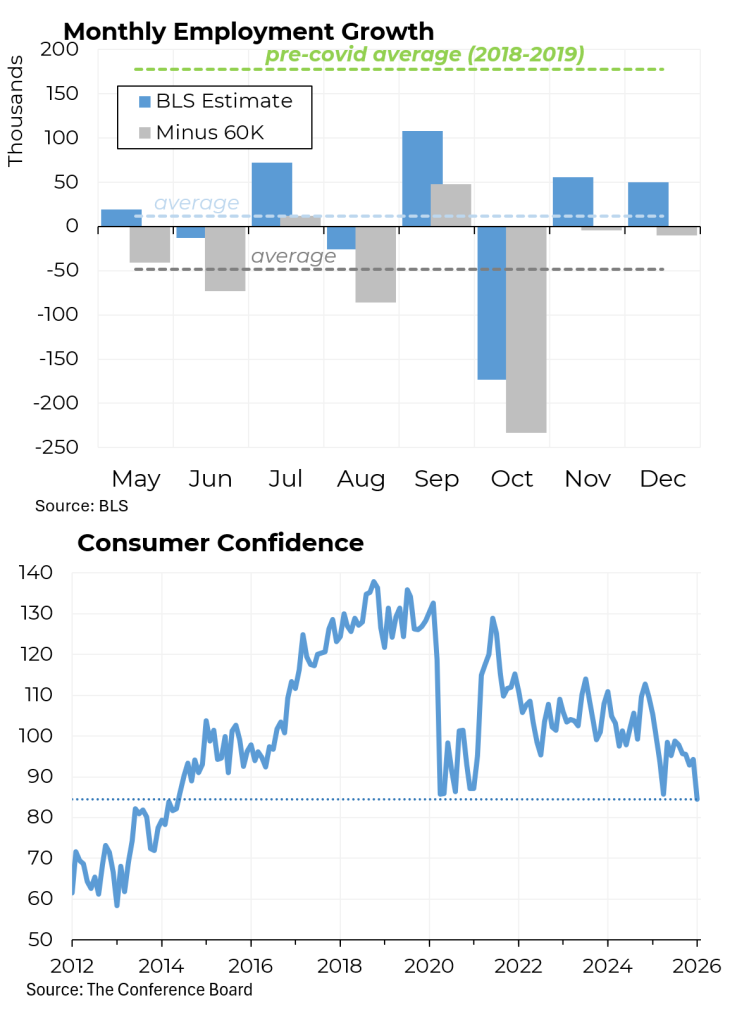

One of the drivers of the recent growth spurt has been a surge in productivity— a key measure of how much output is being generated by each worker. Economists have great difficulty projecting productivity growth but the recent surge appears to be related to both efficiency from artificial intelligence and efforts by businesses to hold down wage costs amidst the uncertainty from tariffs and other factors.

The flip side of strong productivity growth is that it reduces the demand for workers. Indeed, the labor market continues to be weak, with an average of fewer than 12,000 jobs a month having been created since May and the unemployment rate having risen from a low of 3.4% in April 2023 to 4.4% at present. In addition, Fed chair Jerome Powell has said that certain statistical anomalies suggest that the economy may have shed an average of as many as 48,000 jobs a month over that period.

Weak job creation and lingering inflation have left Americans in a sour mood. Earlier this week, the Conference Board released its latest monthly consumer confidence reading, which showed that this important measure was at its lowest level in 12 years.