President-elect Donald Trump will ring the opening bell at the New York Stock Exchange today, a visible symbol of both Trump’s focus on the importance of rising share prices as well as the remarkable performance of the market, particularly over the past two years. But higher stock prices don’t benefit all Americans and the gap in performance between corporate profits and incomes earned by working Americans has become increasingly pronounced, likely contributing to the nation’s dyspeptic mood.

The stock market has been on a tear. The Standard & Poor’s 500 index rose by 24% last year and is up another 27% so far in 2024. On an annualized basis, its performance was roughly comparable under four of the last five presidents — annual increases in the mid-teens under each of them. Only under George W. Bush did the market decline, as he faced both the deflating of the dot.com bubble and the 2008 financial crisis on his watch. Nonetheless, this recent pattern is not aberrational; the market has historically performed better under Democratic presidents than under Republican ones.

The exceptional performance of the market since the financial crisis has been driven partly by rising corporate profits (more about that below) but also by valuations becoming stretched. As a multiple of earnings (the conventional way to value stocks), stocks today are more expensive than they have been any time in the past 120 years except for the period before the dot-com bubble. That, of course, does not mean that they can’t go higher.

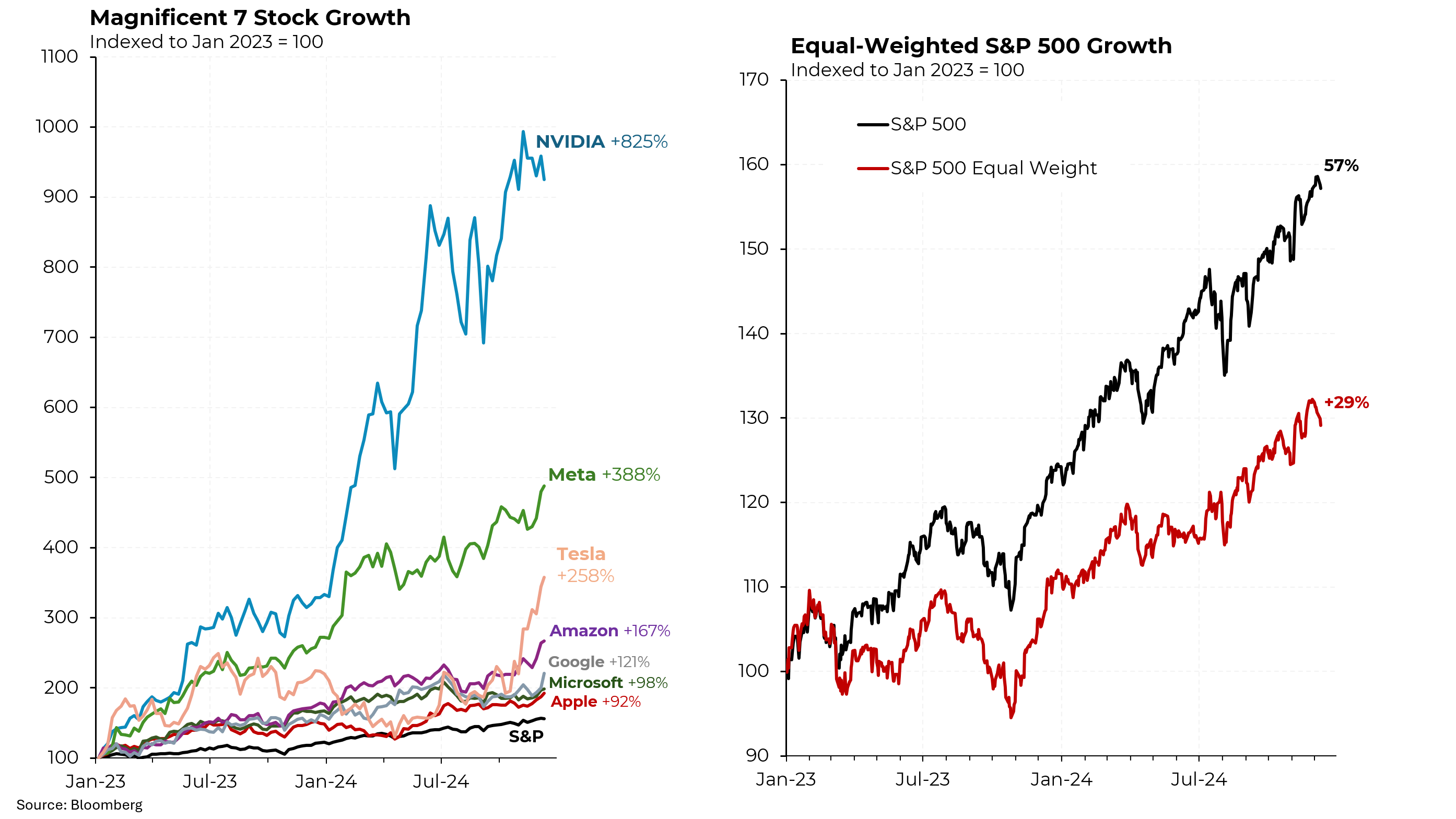

Part of why the stock market has gone up so much has been because of the performance of seven stocks, which have been dubbed the Magnificent 7. All of them, including Tesla, are essentially technology companies. The chip designer, Nvidia, has led the pack, rising more than nine-fold. Meta (formerly known as Facebook) is second. But even the most sluggish of the group, Apple, has nearly doubled in the past two years. (By comparison, the S&P 500 has risen by 57%.)

The 500 companies are included in the index based on their total market valuations. That means that the Magnificent 7 — just a small fraction of the total number of companies — accounts for 33% of the index. If the index were constructed instead so that each company received a 2% weight in the index, the S&P would have risen by only half as much, 29% versus 57%.

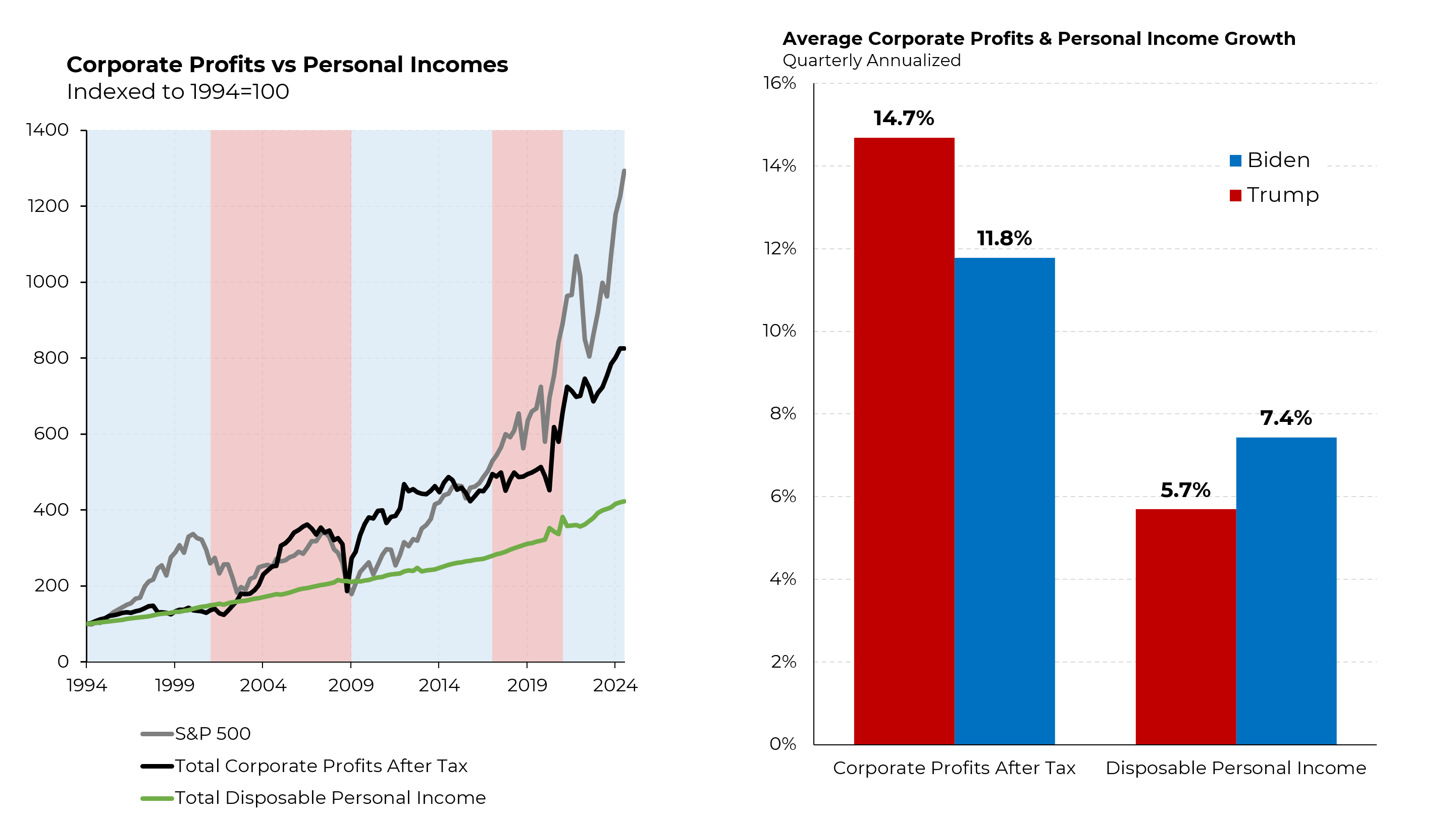

Rising valuations are just one of the reasons why stocks have gone up so much. The other reason is the large increase in corporate profits, which have grown substantially faster than personal income, particularly since the financial crisis. This disproportionate division of the fruits of our economic prosperity may well be playing a role in the social unrest that is so clearly evident.

Under then-President Trump, after tax corporate profits grew at a 14.7% annual rate while incomes increased by just 5.7% per year. (Note that some of the post-Covid spike in corporate profits may be due to low interest rates and government intervention to help small and medium-size businesses.) Under Biden, the gap was smaller but still pronounced: an 11.8% rate of growth of corporate profits and a 7.4% increase in incomes.