Originally published in the New York Times.

After a couple of tough years, 2022 felt like a step back from the brink. The terror of Covid receded. A new president who had seemed on the precipice of failure basked in a fistful of legislative successes. And perhaps most important, Donald Trump’s grip on a large segment of the country showed signs of finally beginning to loosen.

But let’s not uncork the champagne just yet. Inflation continued to bedevil the economy, leading to large interest rate increases and stock market declines. International issues — from the stalemate in Ukraine to rising tensions with China — intensified. The belligerent voices of the extreme right seemed to only get louder.

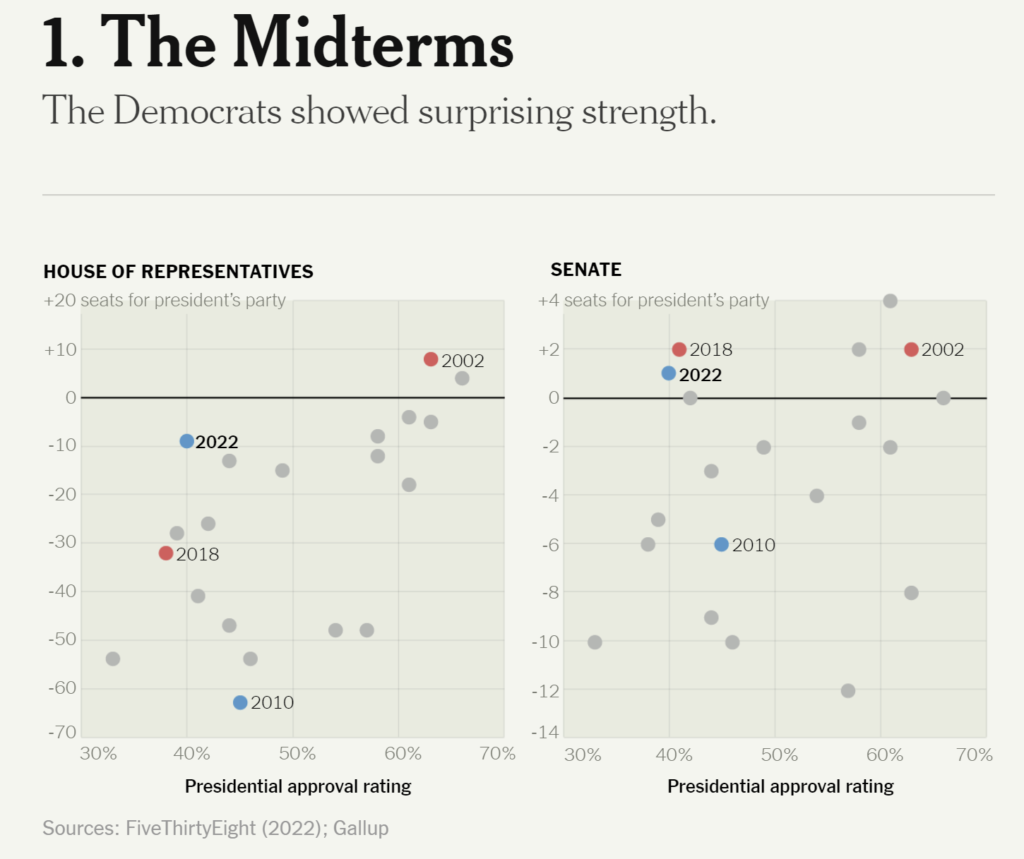

Among the happy surprises of the year was the Democrats’ unexpectedly strong performance in the midterm elections. With President Biden’s approval ratings deeply underwater, history would have suggested a big Republican victory: a loss of perhaps four seats in the Senate and 40 in the House. Instead, Democrats ceded just nine seats in the House, barely losing control of the chamber, and gained a Senate seat. (Notably, it was the first midterm since 1934 that the party in power retained all of its Senate incumbents.) With the benefit of hindsight, pundits ascribed the surprise outcome to factors ranging from too many Trump-like Republican candidates to the Supreme Court’s decision in June to overturn Roe v. Wade.

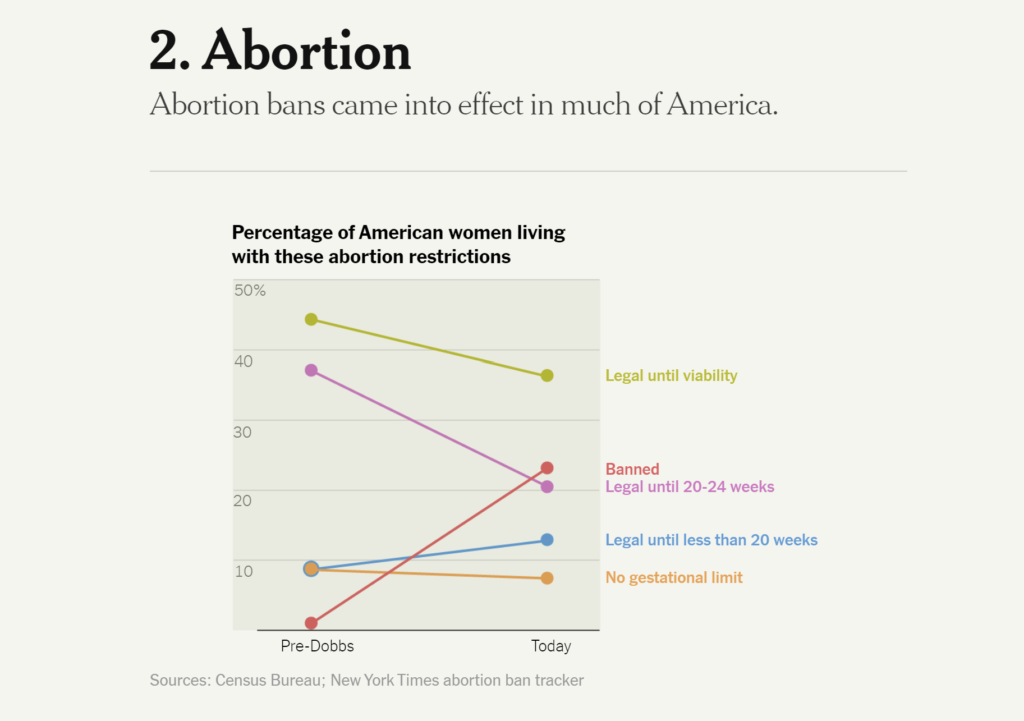

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling, access to abortion almost immediately began to erode as anti-abortion “trigger laws” went into effect and Republican-controlled state legislatures passed greater restrictions. By the end of 2022, 23 percent of American women resided in states with effective bans on abortion. Still more women found themselves living in states that had sharply limited the window in which terminating a pregnancy would be permitted. These changes don’t reflect public opinion: Since Dobbs, voters in Kansas, Kentucky and Montana have rejected anti-abortion ballot measures. Nationally, a July poll found that 62 percent of Americans believe abortion should be legal, at least in most cases.

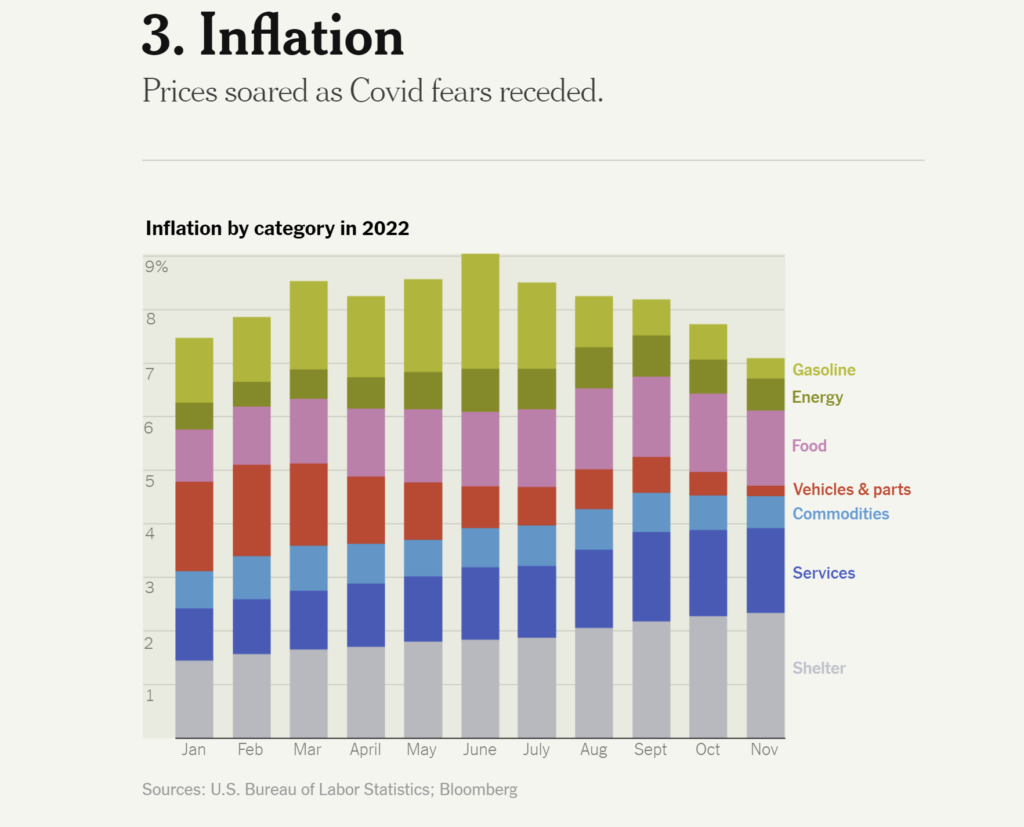

For a substantial majority of Americans, the economy remained the most important issue as prices continued to rise rapidly, with the inflation rate reaching a peak of 9.1 percent in June. Happily, the overall rate then began to decline, falling to 7.1 percent in November. But because of the volatility of food and energy prices, economists often pay more attention to the “core” rate, which excludes those categories. That rate has remained stubbornly high, at 6 percent, far above the Federal Reserve’s target of 2 percent. As the year progressed, the major contributors to core inflation shifted from goods (the Covid buying frenzy subsided) to housing and services like travel and hospitality.

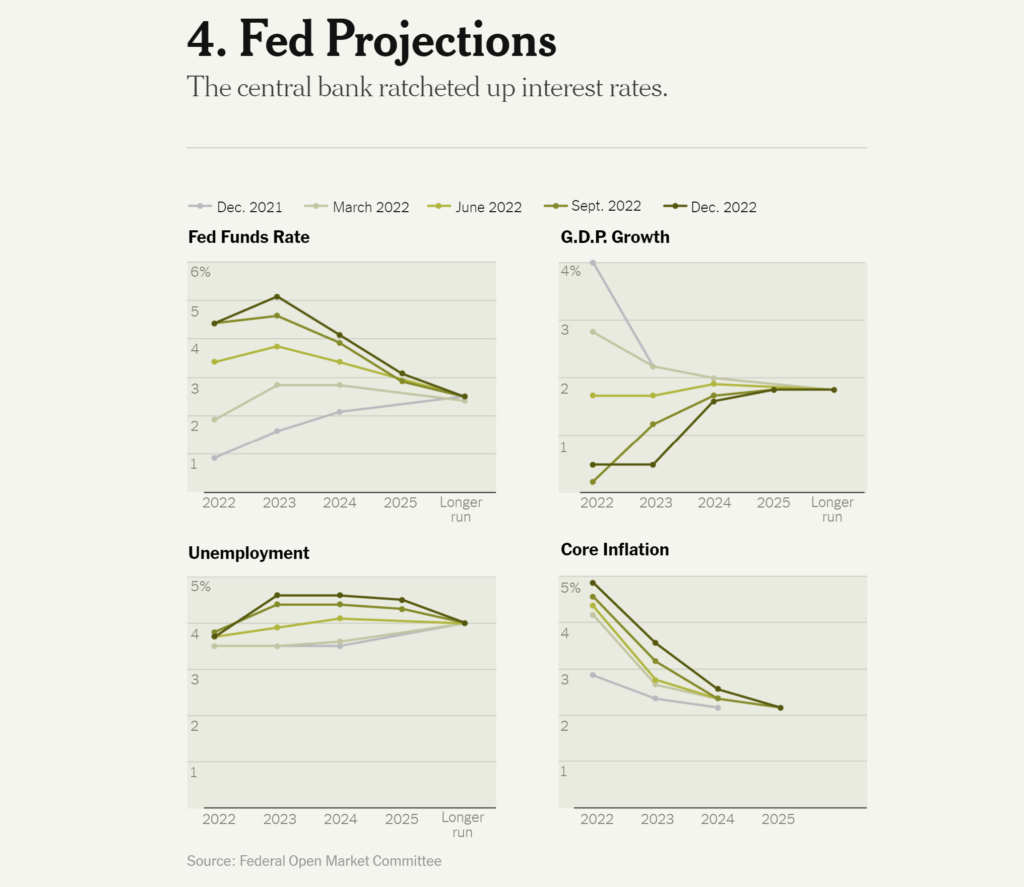

The sustained period of high inflation left the Fed playing catch-up, as it had initially believed that the surge would prove transitory. The central bank imposed stiff interest rate increases and projected that more are still to come. As recently as a year ago, the bank predicted that the federal funds rate would barely exceed 2 percent by 2024; it now expects the rate to be more than 5 percent in 2023. The bank’s projections for inflation, unemployment and economic growth all deteriorated during the year. Even those forecasts may prove too optimistic — while the Fed expects the economy to eke out a small amount of growth in 2023, most economists expect a recession by late 2023 or early 2024.

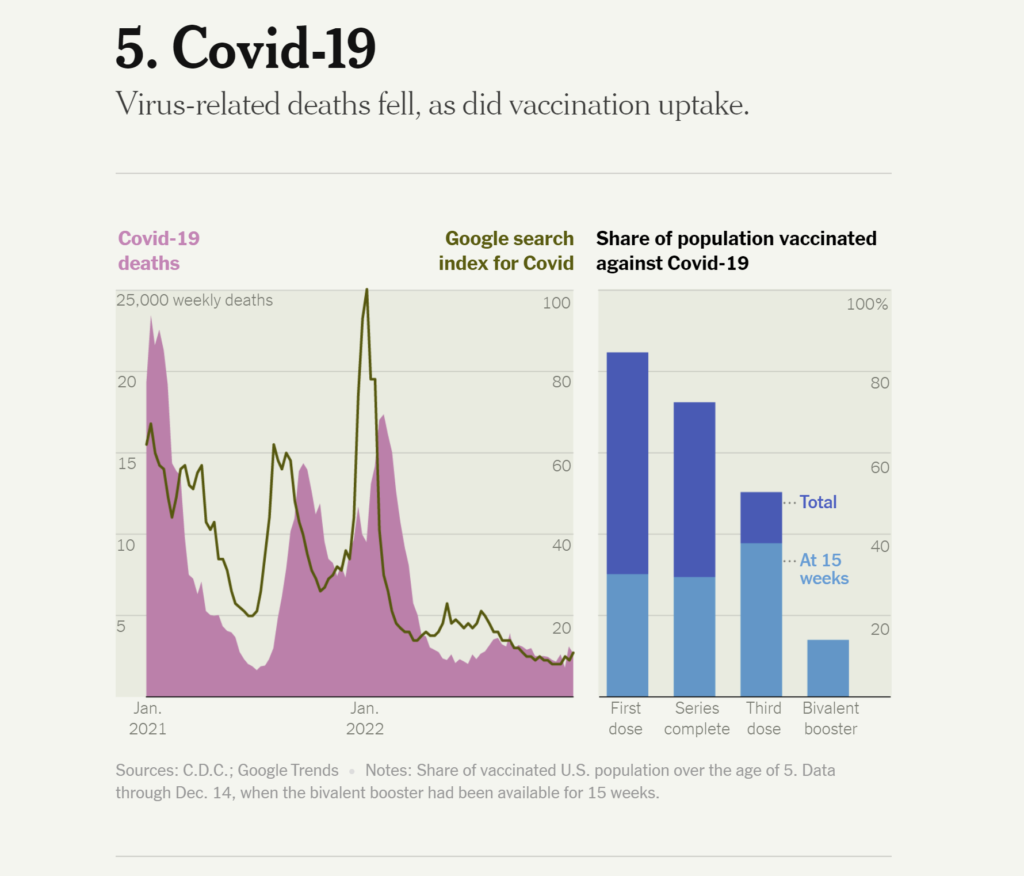

After two years of Covid dominating the headlines, the virus mostly slipped from the front pages as deaths fell from over 3,000 per day in January during the Omicron spike down to fewer than 400 per day near the end of the year. While the return to relative normalcy was welcome, too many Americans ignored the urging of public health officials and shunned the recommended boosters. A plea by Mayor Eric Adams for New Yorkers to resume mask-wearing and get boosters, for example, had no discernible impact, with only 12 percent of residents receiving the fourth injection.

Along with Covid, the supply chain problems that bedeviled businesses and consumers began to ebb. Shipping times from Asia, which had hovered below 60 days before Covid, and jumped to over 110 days early in 2022, had fallen back to less than 80 days by year-end. Transport costs also fell — the Shanghai shipping price index, which had quintupled from January 2020 to January 2022, fell back to just 10 percent above January 2020 levels. Domestically, production delays continued, with more than a third of American manufacturing plants reporting shortages of materials and labor. That, in turn, meant continuing frustration for Americans trying to shop, whether for the holidays or their other needs.

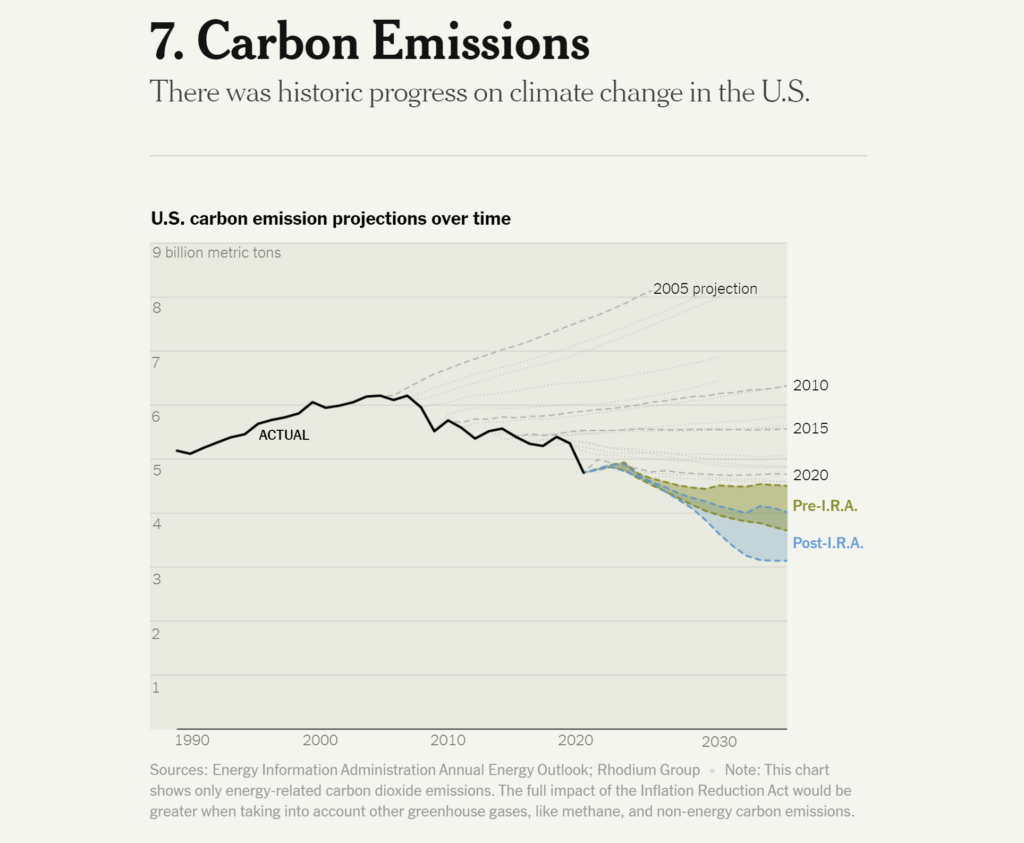

It was a busy year in Washington. Congress passed important legislation to address weaknesses in presidential election certification and our faltering international position in semiconductor production as well as the oddly named Inflation Reduction Act, our most important step to date to attack climate change. The measure allocated nearly $400 billion to clean energy, largely via tax credits, and a smaller amount to loan programs, research and the like. While we have already been reducing our greenhouse gas emissions, the Inflation Reduction Act is projected to reduce those emissions by an additional 10 percentage points by 2030. That would put our projected emissions in 2030 at 60 percent of 2005 levels. Under the Paris agreement, we need to be at 50 percent of 2005 levels in 2030, so there is important work left to do.

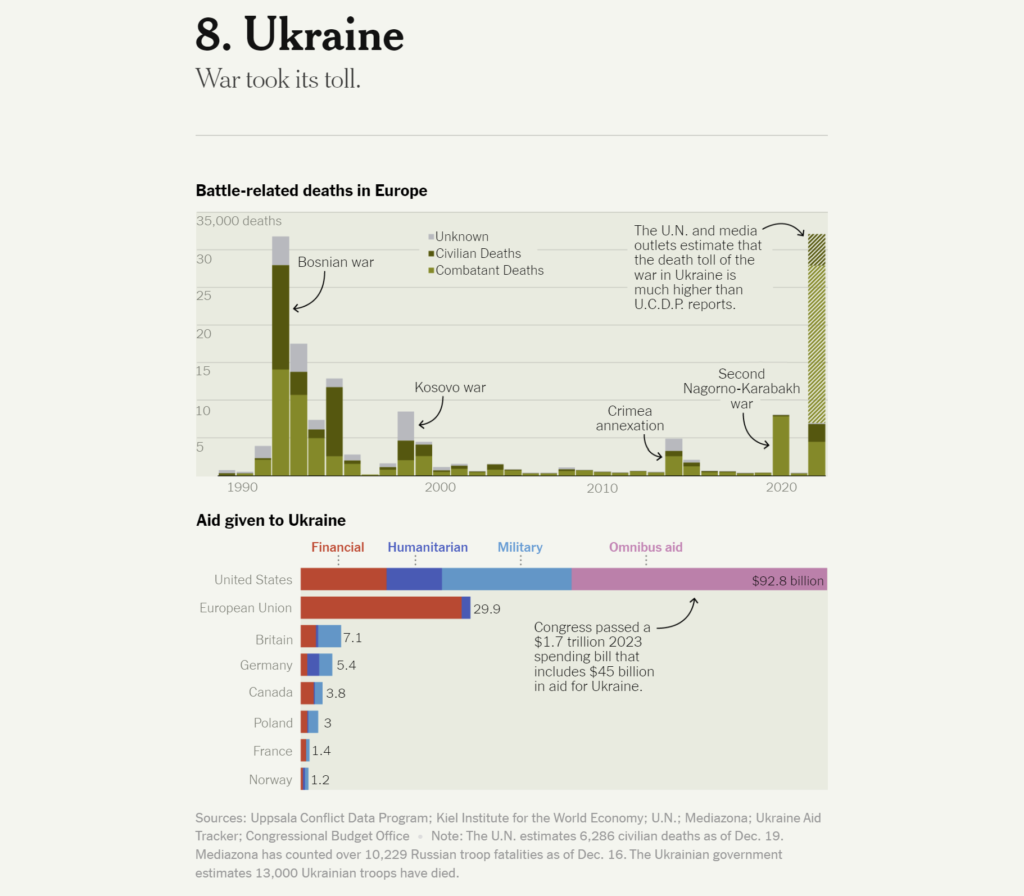

The invasion of Ukraine quickly became a kind of proxy war pitting Russia against the United States, Europe and many other nations. In human terms, the war has been among the deadliest Europe has seen in several years, and the true toll is likely higher than officially recorded. While Ukrainians and Russians are mainly doing the actual fighting, an enormous amount of financial, military and humanitarian aid has flowed from the United States and Europe — almost $50 billion from us alone, with $45 billion more on the way. The war also caused huge disruption in world energy markets — particularly for European nations that relied on Russian natural gas — and contributed meaningfully to the global inflation problem.

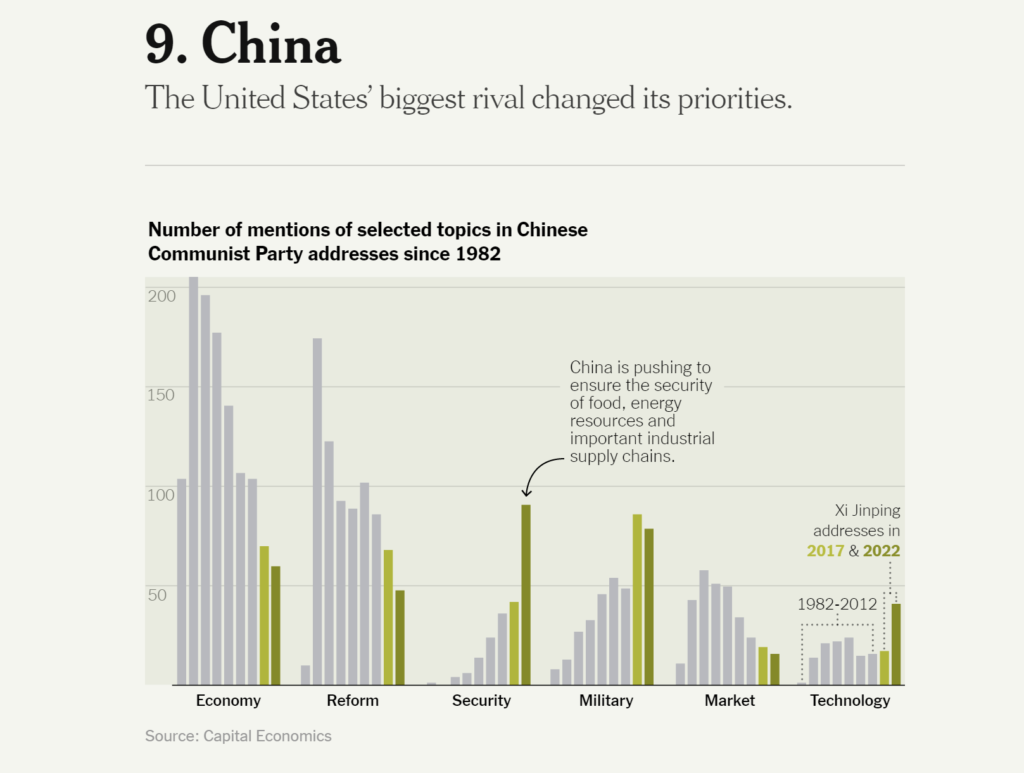

Then there was China: Our biggest source of imported goods became ever more clearly our biggest strategic adversary. President Xi Jinping was elected to an unprecedented third five-year term and quickly packed the Standing Committee, the seven-member core group of the Politburo, with loyalists. In both statements and policy, Mr. Xi continued to emphasize security and the military and to partly reverse China’s movement toward greater free enterprise. This along with the country’s incoherent Covid policies caused a significant slowdown in the economy and a sharp drop in stock prices. As the year ended, Mr. Xi pivoted modestly in an effort to reassure both his citizens and investors that his vision for China included a growing market economy.

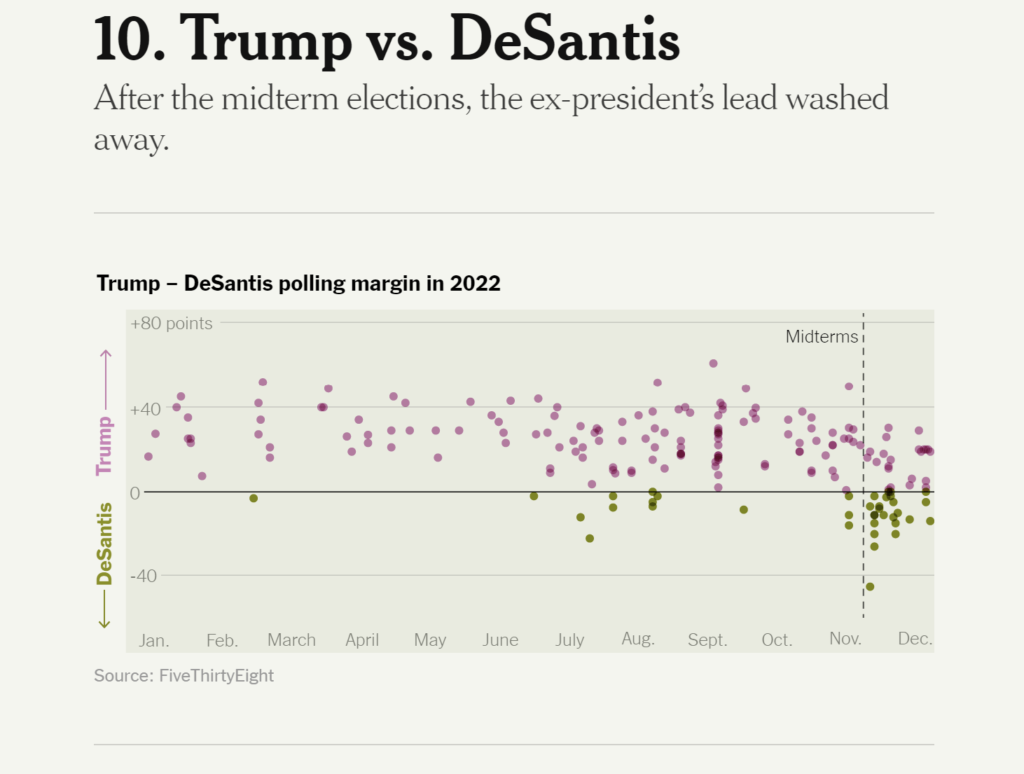

While Mr. Trump may be out of the White House, he was not out of the political arena. For most of the year, his popularity, at least among Republicans, remained strong. In polling data, he stood well ahead of his perceived principal rival, Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida. But after the disastrous midterms, the mood of his party seemed to shift. His margin in polls for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination over Mr. DeSantis fell from an average of 22 percentage points to just 1.4. Many other factors contributed to Mr. Trump’s troubles: his retention of classified documents at Mar-a-Lago, his dinner with a white supremacist, the recommendation of the Jan. 6 committee that he be criminally prosecuted and the release of his tax returns. Oh, and of course his ridiculous hawking of digital trading cards.