Originally published in the New York Times.

Even in Washington, miracles sometimes happen.

Less than a week ago, any tax and spending deal in Congress — let alone a meritorious one — seemed utterly implausible. But the new package announced on Wednesday is a step in the right direction on several of our pressing economic challenges.

While substantially less ambitious than its previous incarnation, Build Back Better, it would reduce the deficit (by the most in more than a decade) rather than increase it, and it would do so without the gimmicks built into B.B.B. Largely through the dogged efforts of Chuck Schumer, the Senate majority leader, and Senator Joe Manchin III, Democrat of West Virginia, Congress sits on the brink of passing historic legislation.

This bill would use tax increases to nudge the economy toward lower inflation while addressing the pressing priorities of climate change and fast-rising prescription drug prices. In the process, the tax system would be made fairer by forcing profitable corporations to pay at least some taxes while eliminating the notorious carried interest loophole (of which I have benefited significantly).

How does this package attack inflation? Excessive inflation is principally a function of too much demand relative to available supply. To reduce inflation, we need to curb demand (as distasteful as that may be). The Federal Reserve plays the principal role in this process by raising interest rates (as it did last week). That causes companies and individuals to borrow less and exerts a particularly strong downward draft on sectors like housing, which is highly sensitive to rising rates.

But fiscal policy also affects prices. Until last week, Mr. Manchin was arguing that higher taxes could exacerbate inflation. That’s simply a misunderstanding of basic economics.

Higher taxes used to lower the budget deficit are deflationary. They take money out of the economy, thereby reducing demand, as the Schumer-Manchin package aims to do. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget called it “a welcomed improvement,” a proposal that, with interest, could reduce the deficit by $100 billion annually by 2032.

While that’s enough to produce only a modest deflationary impact, it’s an important move in the right direction when too much recent policy has pushed the wrong way.

As with any complex package, we need to understand the details, particularly the many different pieces of the climate package, to be sure they are thoughtful and effective. (The several Covid relief bills were stuffed with wasteful provisions.) I’m particularly skeptical of the efficiency of government grant programs (of which there’s a small flotilla in the legislation), as opposed to using tax incentives and penalties to bend behavior through market forces.

But happily, the climate pieces of the new package are highly tilted toward tax incentives. And early analysis by Rhodium Group found that the climate provisions would put the United States meaningfully closer to meeting our 2030 commitments under the Paris Agreement.

To be sure, the package is not perfect. Nearly two decades after Congress agreed to prevent Medicare from negotiating drug prices to win approval of a prescription benefit plan, that mistake will finally be unwound — although only for a limited number of drugs and very slowly over most of a decade.

And importantly, the 15 percent corporate minimum tax is not the best way to ensure that companies pay their fair share. Many of the biggest companies don’t pay taxes because of the cuts embedded in President Donald Trump’s 2017 tax legislation. Instead of the more desirable approach of unwinding those, the new bill takes the simpler approach of a flat 15 percent tax on each large company’s accounting of its profits (known as book profits) rather than its profits as calculated using the tax code. This would create both distortions and a greater potential for manipulation by tinkering with accounting methodologies.

And most regrettably on the tax front, the Schumer-Manchin compromise does not include the global tax agreement that Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen admirably negotiated with dozens of other countries to reduce the incentive for companies to lower their taxes by shifting profits around the globe.

Nor does it include some meritorious pieces of B.B.B., such as extending the child tax credit, although more tax increases would have been needed to pay for them.

In Washington — as in life — we should not let perfect be the enemy of the good, and there is an abundance of good in this legislation. That includes roughly $80 billion of new funding for the Internal Revenue Service for enforcement; for years, Republicans have tried to starve the I.R.S. so that rampant tax avoidance could continue largely unrestrained.

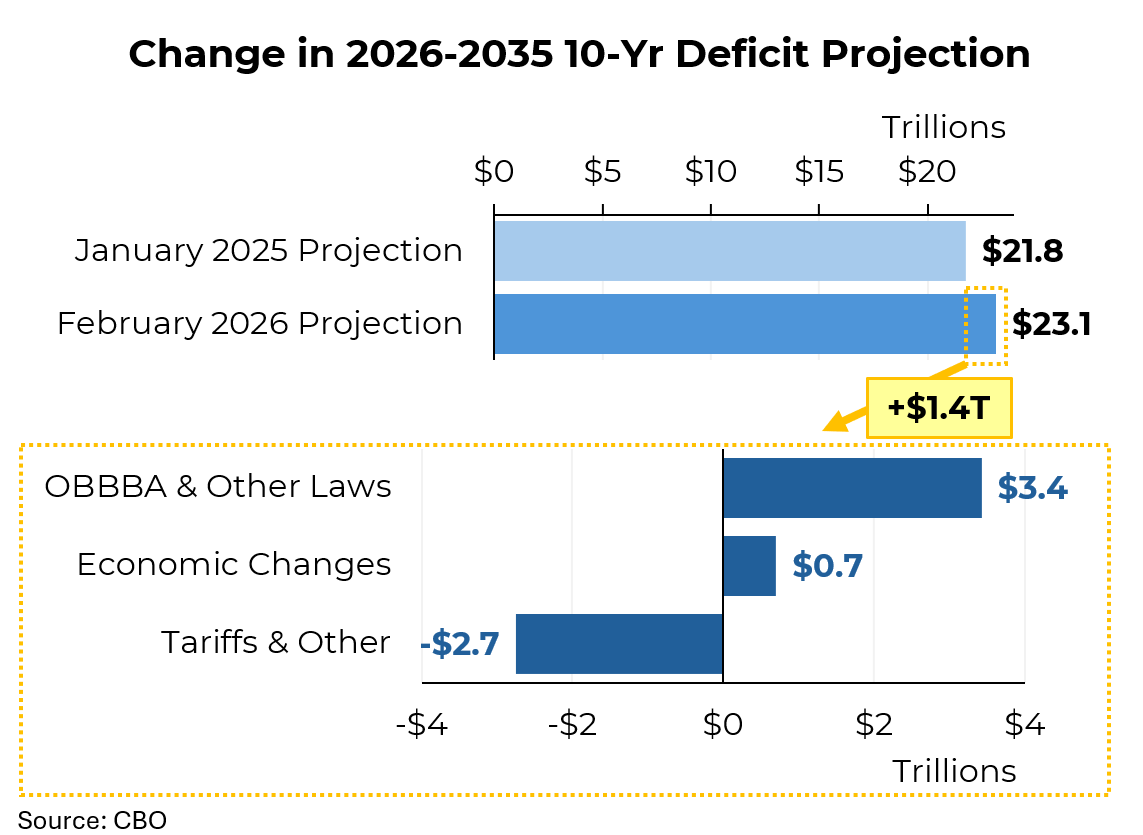

Coincidentally, on the same day that the Schumer-Manchin compromise was announced, the Congressional Budget Office released its latest fiscal estimates, showing that, absent extensive legislative changes, the nation’s deficit will remain around $1 trillion annually and soon begin escalating.

Making even a modest dent in this while addressing major challenges qualifies this legislation as one of the best packages that I can remember Congress giving birth to.