Originally published in the New York Times.

Enough already about “transitory” inflation. Last Wednesday’s terrible Consumer Price Index news shifts our inflation prospects strongly into the “embedded” category: Prices are up 6.2 percent from a year ago, the largest increase in 30 years.

While not likely to morph into the double-digit inflation I covered for The New York Times four decades ago, prices may well rise fast enough to trigger higher interest rates. Higher financing costs make it more expensive for consumers and businesses to borrow, which, in turn, throttles growth.

Inflation had already been tagged as a factor in the Democrats’ awful election results this month and in the president’s sagging poll numbers. It also threatens the passage of President Biden’s Build Back Better plan, which includes expansive new initiatives to address climate change, as well as important programs like paid family leave and universal preschool.

But last Thursday, Joe Manchin, a key centrist Democratic senator, suggested that he may want to delay consideration of the legislation until early next year because of his concerns over its impact on inflation. For the Biden administration, which has long insisted that prices would rise far more slowly, inflation is now its biggest challenge.

How could an administration loaded with savvy political and economic hands have gotten this critical issue so wrong?

They can’t say they weren’t warned — notably by Larry Summers, a former Treasury secretary and my former boss in the Obama administration, and less notably by many others, including me. We worried that shoveling an unprecedented amount of spending into an economy already on the road to recovery would mean too much money chasing too few goods.

From my many conversations with administration officials, lawmakers and informed onlookers in recent months, it’s clear to me that the pressure on the White House, particularly from progressives, to move forcefully was intense.

Emboldened by his victory over Donald Trump, Mr. Biden made clear he believed he had a mandate to effect broad change. Haunted by the response to the 2008 economic crisis, deemed too timid by many experts, his mantra has been that it is better to do too much rather than too little. Maybe — but this much?

The original sin was the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, passed in March. The bill — almost completely unfunded — sought to counter the effects of the Covid pandemic by focusing on demand-side stimulus rather than on investment. That has contributed materially to today’s inflation levels.

Focused on the demand side, even most pessimists — me included — missed a pressing problem. Supply-chain bottlenecks have led to shortages of many goods, a crisis that has been exacerbated by the reluctance of Americans to return to work. The worker shortage has also hurt the service sector. Many restaurants, for example, remain closed because they can’t find workers. Both also spark higher prices.

Now, between the government payments and underspending during the pandemic, American consumers are sitting on an estimated $2.3 trillion more in their bank accounts than projected by the prepandemic trend. As they emerge from seclusion, Americans are eager to spend on everything from postponed vacations to clothing. But the supply chain breakdown has turned the simple act of spending money into a challenge.

For the Democrats, recent disappointing election results and the current legislative logjam offer a dose of cold reality. The administration wanted to claim a big policy win ahead of the 2022 midterm elections. But inflation worries are top of voters’ minds.

So the administration should come clean with voters about the impact of its spending plans on inflation. Build Back Better can be deemed “paid for” only if one embraces budget gimmicks, like assuming that some of the most important initiatives will be allowed to expire in just a few years. The result: a package that front-loads spending while tax revenues arrive only over a decade. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimates that the plan would likely add $800 billion or more to the deficit over the next five years, exacerbating inflationary pressures.

Mr. Biden also insists that the much-lauded infrastructure bill he just signed is fully paid for — but it isn’t. Indeed, the infrastructure figures show $550 billion in new spending and just $173 billion of additional offsets.

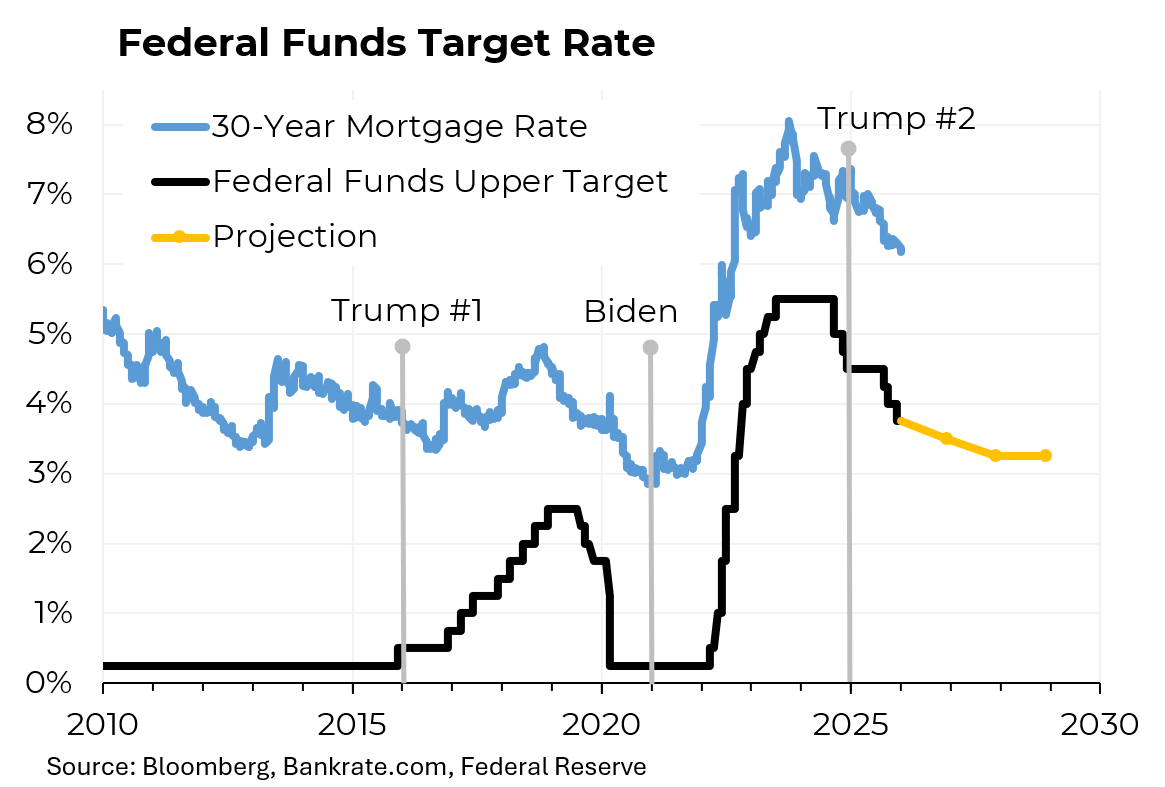

Of course, some responsibility for overstimulating lies with the Federal Reserve, which responded correctly to the onset of the pandemic by cutting interest rates and shoveling money into the financial system. More recently, the Fed has been too slow to curtail its program of buying debt, sending still more money to chase those few goods. And until recently, Fed officials were echoing the White House line about “transitory” inflation.

For the Fed, addressing inflation will mean raising interest rates, perhaps sooner than it thinks necessary. The Fed targets average annual inflation of 2 percent. So if or when the pace of price increases gets stuck far above that level, the central bank will need to raise interest rates to address the problem. While the Fed thinks this won’t happen until late next year, the bond market believes rates will be hiked by midyear.

The responsibility for easing inflationary pressures also lies with the Biden administration. To its credit, it is scrambling to address the supply shortages, doing things like unclogging ports. But other ideas, such as releasing oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, amount to distracting symbolic moves that are unlikely to have a significant effect on inflation.

The White House needs to inject some real fiscal discipline into its thinking. Given the importance of Mr. Biden’s spending initiatives, the right move would be to add significant revenue sources. Yes, that means tax increases. We can’t get back money badly spent. But we can build this economic plan back better.