On MSNBC’s Morning Joe today, Steven Rattner delved into April’s disappointing jobs report, exploring potential reasons why, despite many job openings, Americans are not returning to work as quickly as anticipated.

Friday’s jobs report was, indeed, disappointing. Whether it proves to be an accurate reflection of the state of the economy remains to be seen – my guess is that the news isn’t as bad as the numbers suggest. That said, a number of factors are clearly hurting the pace of rehiring. They include, for example, supply chain problems that have negatively affected manufacturing, as well as continuing concerns among some Americans about the possibility of getting sick.

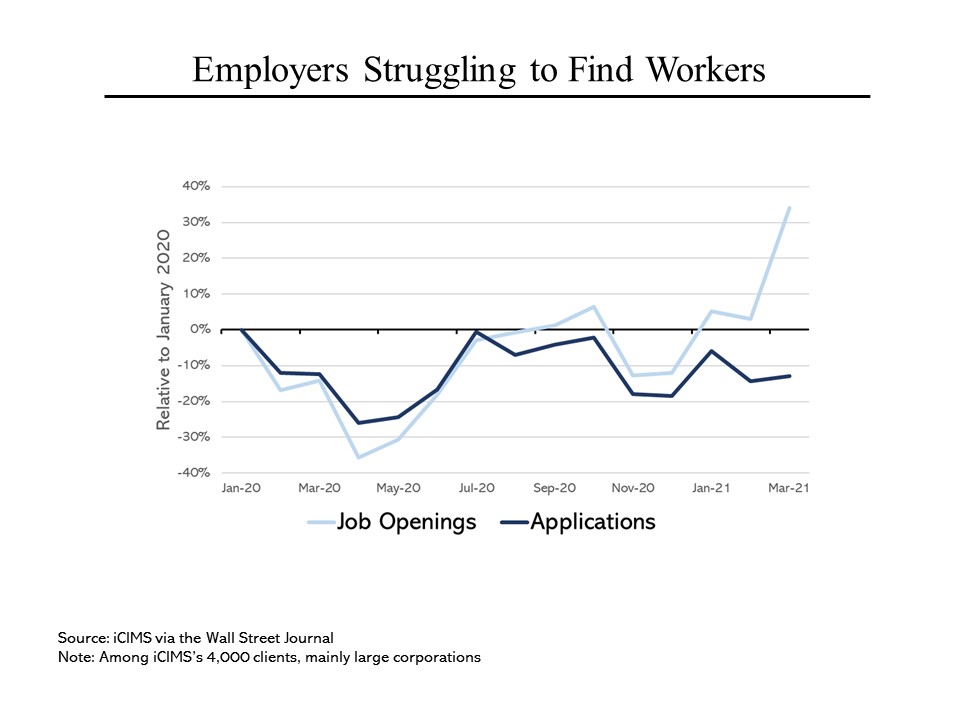

But it’s also clear that all is not perfect in the labor market. Perhaps surprisingly, many employers have reported difficulty in filling open positions. In recent weeks, the number of job openings has soared while the number of Americans applying for jobs has fallen. A few examples: Both Domino’s and Uber say they can’t find qualified drivers. Pilgrim’s Pride, a major poultry processor, is short of workers even as chicken prices are soaring. All told, the National Federation of Independent Business says that a record 44% of all small business owners report having job openings they could not fill.

But it’s also clear that all is not perfect in the labor market. Perhaps surprisingly, many employers have reported difficulty in filling open positions. In recent weeks, the number of job openings has soared while the number of Americans applying for jobs has fallen. A few examples: Both Domino’s and Uber say they can’t find qualified drivers. Pilgrim’s Pride, a major poultry processor, is short of workers even as chicken prices are soaring. All told, the National Federation of Independent Business says that a record 44% of all small business owners report having job openings they could not fill.

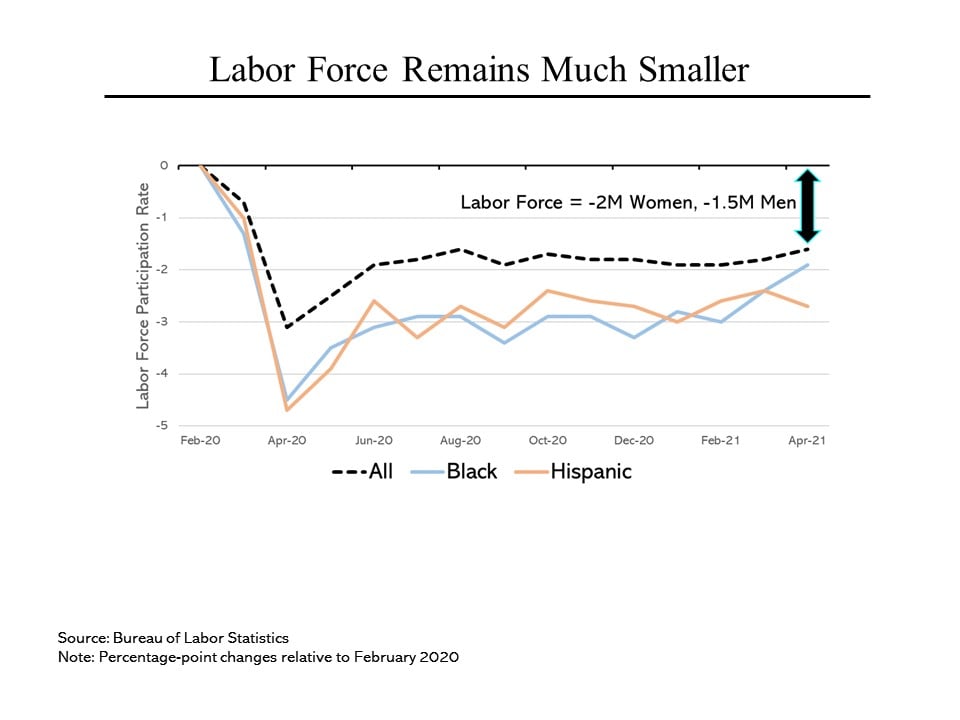

A significant reason is that about 3.5 million Americans have dropped out of the labor force altogether. To put that in perspective, during the Great Recession, “only” about half as many workers left the labor force. And this time around, Blacks, Hispanics and women have dropped out in especially high numbers. Why? For one thing, those groups of Americans lost their jobs in particularly high proportions during the downturn because many cuts occurred in service industries like restaurants and hotels, which are disproportionately staffed by these Americans. For another, the failure of schools to reopen fully for in-person learning has forced some to drop out of the workforce and stay home.

People of color may be discouraged by the particularly high unemployment rates among their demographics. For example, Black unemployment is currently 9.7%, 3.6 percentage points higher than the overall rate. Before the pandemic, the Black jobless rate was only 2.5 percentage points higher than in the nation as a whole.

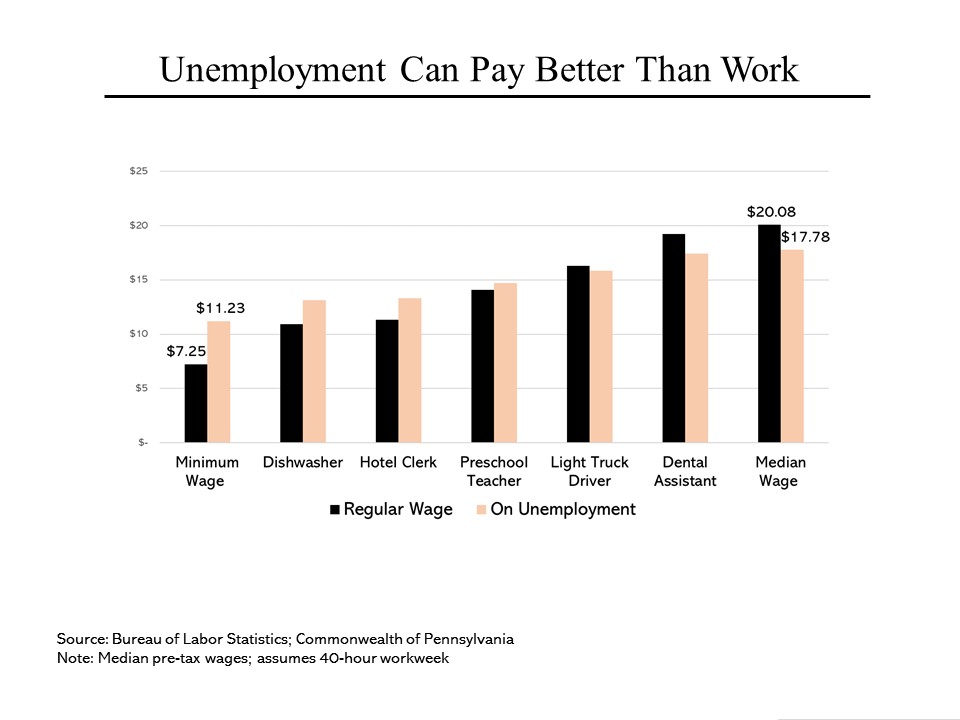

Separate from those who have stopped looking for work (and therefore don’t qualify for unemployment benefits) are those who are nominally still in the workforce but who have been receiving expanded unemployment insurance as well as stimulus checks and therefore may not be fully motivated to gain new employment. Unemployment benefits vary by state and by prior income level. In Pennsylvania, for example, the combination of state payments and the special federal payments total a minimum of $11.23 per hour and as much as $21.80 per hour (assuming a 40-hour week). That’s not much but it is substantially more than the federal minimum wage of $7.25 (which also applies in Pennsylvania) and more than many earn in the Keystone State, including dishwashers, preschool teachers and light truck drivers. As a frame of reference, Pennsylvania’s median wage is $20.08 per hour.

Separate from those who have stopped looking for work (and therefore don’t qualify for unemployment benefits) are those who are nominally still in the workforce but who have been receiving expanded unemployment insurance as well as stimulus checks and therefore may not be fully motivated to gain new employment. Unemployment benefits vary by state and by prior income level. In Pennsylvania, for example, the combination of state payments and the special federal payments total a minimum of $11.23 per hour and as much as $21.80 per hour (assuming a 40-hour week). That’s not much but it is substantially more than the federal minimum wage of $7.25 (which also applies in Pennsylvania) and more than many earn in the Keystone State, including dishwashers, preschool teachers and light truck drivers. As a frame of reference, Pennsylvania’s median wage is $20.08 per hour.

All told, according to a University of Chicago economist, 42% of workers receiving unemployment benefits are making more than their pre-unemployment wage. That may be fine social policy but it’s not likely to encourage job seeking. As a result, some states, including Montana and South Carolina, are ending their participation in the expanded federal benefits early.