Originally appeared in The New York Times.

By any measure, 2018 was another Year of Trump. From his efforts to remake the American economy to his go-it-alone trade war to his curious pro-Putin foreign policy to the at least 17 investigations underway into his various activities, President Trump dominated the news as few of his predecessors have done. But by the end of his second year, the prospects that he would achieve his economic goals were in grave doubt as growth slowed and the stock market swooned.

A 40-Seat Rebuke of an Unpopular President

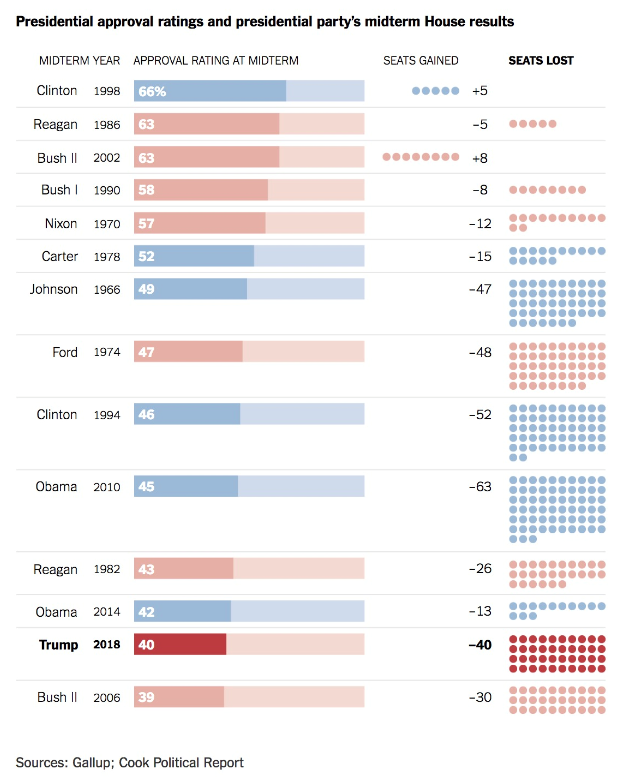

Since Inauguration Day, Mr. Trump’s approval rating, according to the monthly Gallup poll, has averaged 39 percent (a record low for a new president). Voters emphatically registered their disappointment in the midterm elections. As statistical analyses of past midterm elections have shown, the approval rating of the president is more closely correlated to midterm success than the state of the economy is.

This year was no exception. In the House of Representatives, Republicans lost 40 seats (or possibly 41; one race has yet to be called). Meanwhile, Democrats picked up seven governorships. Although the Democrats had a net loss of two seats in the Senate, not one Democrat running for the upper chamber in a state carried by Hillary Clinton lost, while Democrats won in seven states carried by Mr. Trump. Happily, all of this occurred in the context of the highest turnout of eligible voters since 1914.

Alarming Churn in the White House

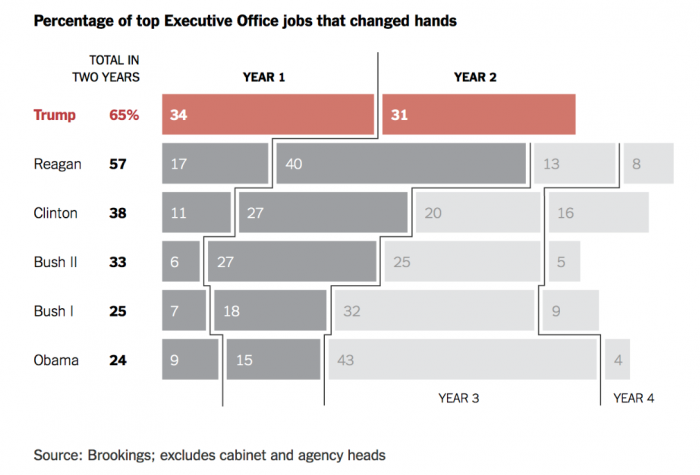

As the departure of Defense Secretary Jim Mattis illustrated, the chaos at the Trump White House is striking relative to past presidents. In two years, 65 percent of the president’s most senior aides have departed. That’s the highest of any president since Ronald Reagan, and it’s similar to the turnover experienced by many of Mr. Trump’s predecessors over an entire four-year term. (President Barack Obama had the lowest turnover, at 24 percent.)

Other fun facts: Mr. Trump has had five communications directors, and with the appointment of Mick Mulvaney as acting chief of staff, Mr. Trump has now had three, a record for the first two years of an administration. Mr. Trump has seen 10 departures from his cabinet, compared to four for Mr. Obama and one for President George W. Bush.

Another Boast Debunked

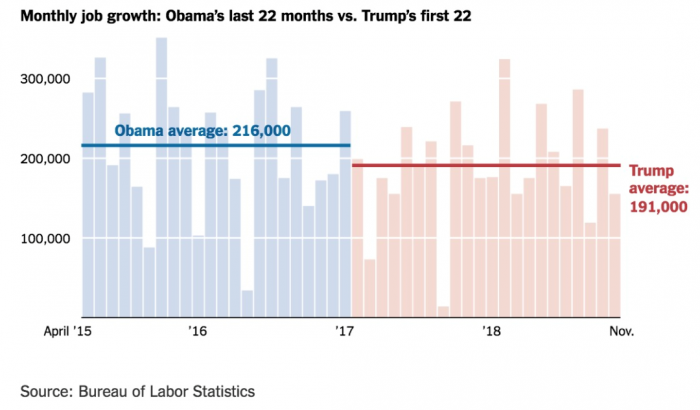

“I will be the greatest jobs producer that God ever created.”

— Donald Trump shortly after the 2016 election

Mr. Trump takes to Twitter frequently to extol the pace of job growth, which has, indeed, been solid. The problem with Mr. Trump’s victory lap is that job growth during his administration has been slightly slower than it was during the last 22 months of Mr. Obama’s tenure: 4.2 million Americans hired under Mr. Trump versus 4.8 million under Mr. Obama. More worrisome is that Mr. Trump’s policies have done little to help manufacturing workers, whose votes in key states helped elect him; their share of total employment has not improved.

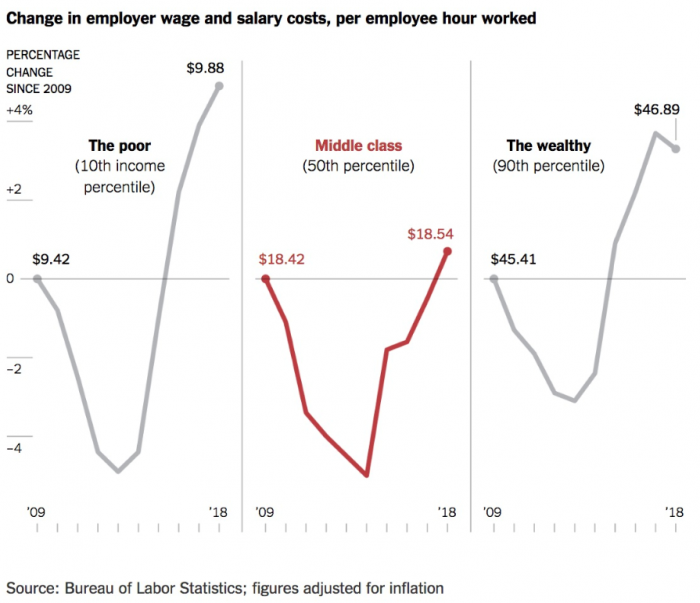

A Paltry Raise for the Middle Class

While jobs capture the headlines, an equally important measure is wages. There, the news is not good. Real wages (after adjusting for inflation) have barely grown under Mr. Trump; President Obama fared modestly better. And the principal beneficiaries of the wage increases that have occurred have been Americans with incomes in the top 10 percent and in the bottom 10 percent.

The former is not surprising; the latter has to do in large part with high demand for unskilled workers (think of the pay increases put in place by Amazon and Wal-Mart) together with increases in the minimum wage by many states. That has left the middle 80 percent of Americans with wages that continued to decline in real terms through 2017 and only inched up in 2018. This will prove yet another challenge for Mr. Trump as he tries to convince voters in 2020 that his economic program is working.

Billions in Tax Cuts, but Not the Promised Growth

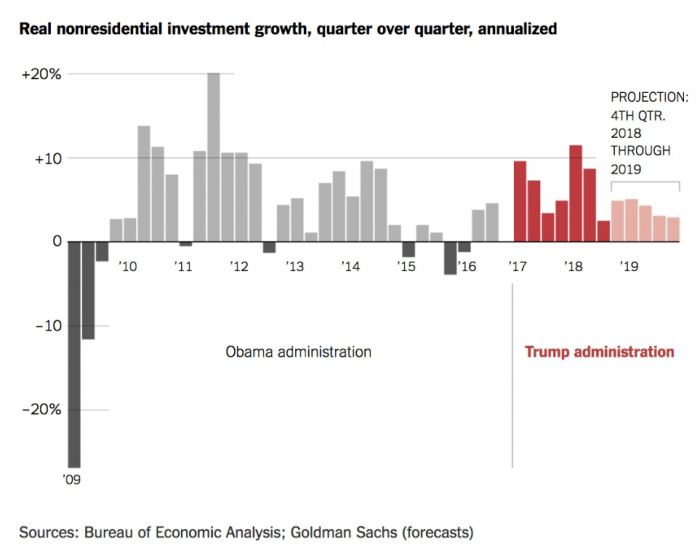

The centerpiece of Mr. Trump’s program was the $1.9 trillion tax cut that was passed in December 2017 amid promises of an immediate investment boom. So far, that has proved a mirage.

Yes, investment did jump in the first half of 2018 — when you provide huge tax subsidies for investment, it’s no surprise that companies will do more of it. But that surge evaporated in the third quarter. Goldman Sachs is predicting a less than 5 percent increase in investment next year.

For new investment to raise the economy’s growth rate over a longer term, it would have to climb to a much higher level and stay there, which appears unlikely. So much for the argument, presented in a letter from nine respected conservative economists to Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, that the tax cut would raise the growth rate for G.D.P. to 3 percent to 4 percent.

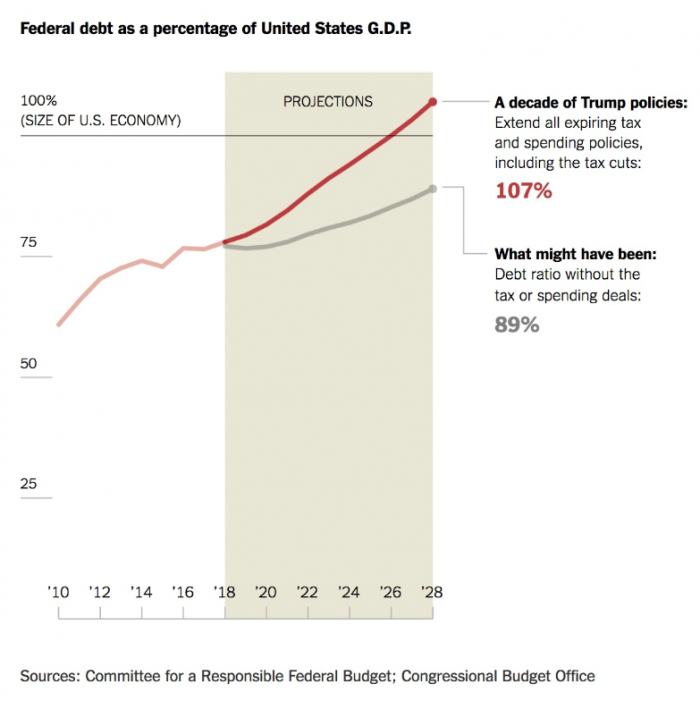

A Debt Bigger Than the G.D.P.

The tax cut, combined with an equally formidable new spending bill, is producing one of the biggest peacetime federal budget deficits. As low as $439 billion in 2015, the fiscal gap is now on track to exceed $1 trillion in 2020. Over the coming decade, that could mean $16 trillion more in federal debt.

If all the tax law’s provisions are extended, the ratio of debt to gross domestic product for the United States will exceed 100 percent for the first time since World War II. Among the many unpleasant consequences of that: Annual interest on the national debt will be higher than the cost of defense and also of Medicaid by about 2022.

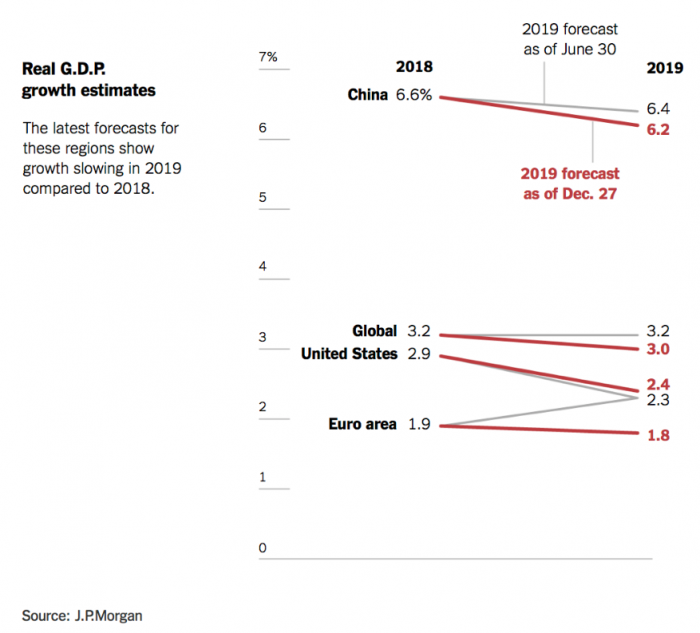

The Worsening Global Outlook

In recent weeks, the United States stock market has lost all of its gains since September 2017 — gains that Mr. Trump claimed resulted from his economic policies. The stock market is on track for its worst December since 1931. What’s going on? After a burst of economic optimism, investors have turned bearish, and chatter about a coming recession is becoming more common.

Since June, JPMorgan has cut its global growth forecast from 3.2 percent to 3 percent. That may not sound like much, but it’s an estimated $170 billion of lost output. China is feeling shaky and Europe — grappling with problems ranging from Brexit to weak Italian banks — is faltering. As for the United States, perhaps only Mr. Trump believes we will achieve the promised 3 percent plus growth next year; about 2.5 percent seems more realistic, and some economists expect an even greater slowdown.

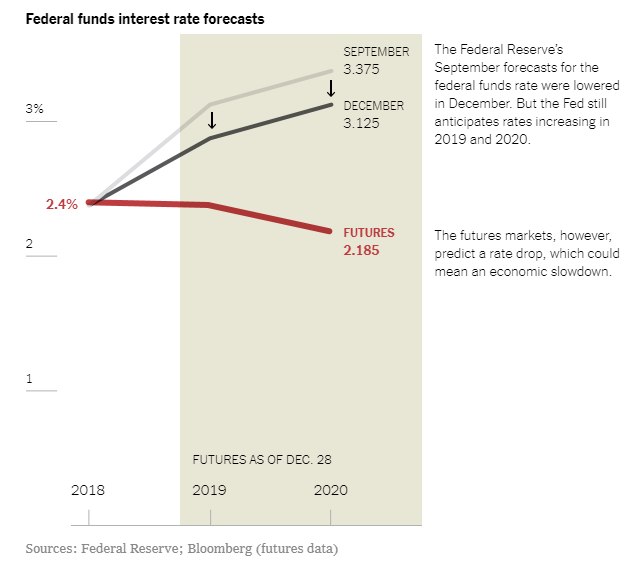

A Bad Sign for the Economy

The Federal Reserve did all it could to telegraph December’s rate increase. Yet the stock market promptly swooned. That was because the Fed only modestly cut back on its expectations for interest rate increases in 2019, to two from the three previously forecast. But the futures markets, which have historically been better predictors than the Fed itself, foresee no rate increase next year and a cut in 2020.

That’s good news for those who will be borrowing for homes or cars, but it’s a bad signal for the economy as a whole, because it suggests that economic weakness may be coming. It’s particularly bad news for Mr. Trump, who could find himself running for re-election in a slowdown or even a recession. After four years in office, it’s going to be very hard for him to pin that on Mr. Obama or the Democrats.

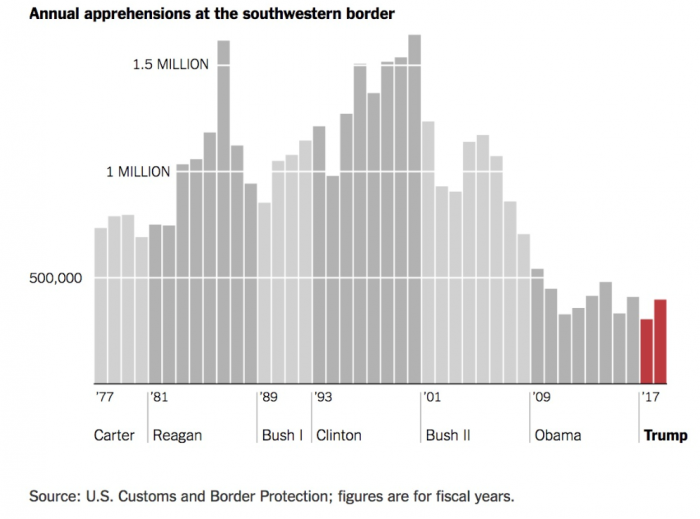

Apprehensions at the Border Remain Low

If your only source of news was Mr. Trump’s tweets, you might assume that illegal immigrants are flooding across the borders of the United States. The reality is different. Since 2000, when about 1.6 million people were apprehended at the southwestern border, the total has plummeted and is now hovering around 400,000.

It’s true that the mix has changed: Fewer Mexicans attempt to cross as their country’s economy improves, but violence and poor economic conditions have sent many families from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador heading north. I’ll spare you the usual argument about the contribution that immigrants make to America, but here’s one interesting fact: The incarceration rate for illegal immigrants is only half that of people born in this country — and that includes those jailed for immigration offenses.

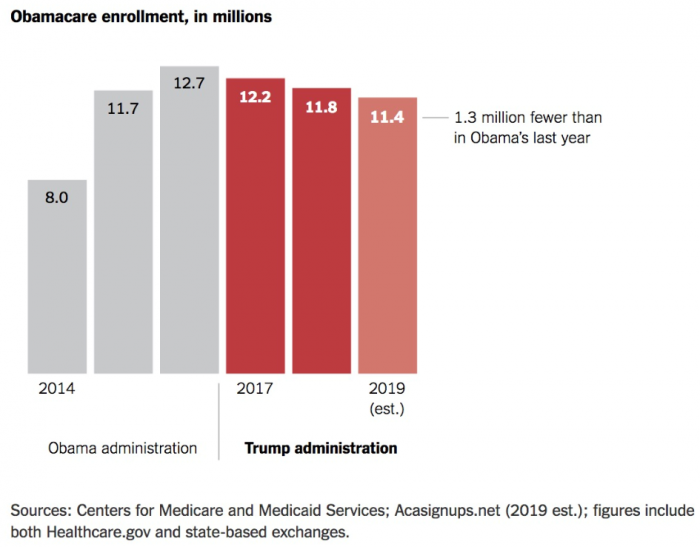

Doing Their Best to Sabotage Obamacare

Less noticed amid Trump news has been slipping enrollment in the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare. From a peak of 12.7 million enrollees in 2016, sign-ups through the exchanges have been declining.

The total for 2019 is projected to be approximately 11.4 million, according to Charles Gaba, an analyst who follows Obamacare closely. He attributes that decline, in part, to “sabotage.” The requirement that all Americans have health care has essentially been gutted. The open enrollment period was cut by half. Funding for “navigators” who help people enroll, was slashed. Advertising was reduced by 90 percent. And a federal judge in Texas recently issued a decision that could invalidate Obamacare altogether.

The only good news is that after several years of hefty raises by insurance companies fearful of losing money on the new product, premium increases have slowed significantly and may fall slightly in 2019.