Originally appeared in the New York Times

In 2016, as he crisscrossed the country for his presidential campaign, Donald Trump promised repeatedly that he would make American factories great again. “My plan includes a pledge to restore manufacturing in the United States,” he told a cheering crowd in the nation’s automobile capital, Detroit.

In truth, Mr. Trump’s promise was false hope, a cynical campaign pledge divorced from economic reality. That was illustrated vividly this week when General Motors announced that it would cut about 14,000 jobs.

Mr. Trump promptly attacked the company, but he is tilting at the wrong windmill: Rather than some arbitrary downsizing, the company’s decision was a rational response to many worrisome factors.

Its sales have begun to soften. Consumers have shown little interest in small cars, and G.M. lacks a strong line of crossover vehicles. Like many of its competitors, the company continues to increase production at less costly Mexican plants. Electrification, in particular, will vastly change the types of factories and workers that G.M. needs. What’s more, the whole industry faces disruption by the sudden rise of ride-sharing apps and other innovations that will discourage vehicle sales.

Having served as head of President Barack Obama’s Auto Task Force, I might be expected to be critical of G.M., which received more than $50 billion of government assistance. (All except $11.2 billion was ultimately repaid.)

But I’m not. When Mr. Obama decided to save the auto companies in 2009,electric cars were just beginning to be produced, ride sharing was in its infancy, and I can’t remember a single expert telling us that self-driving vehicles would arrive in my lifetime.

Some critics argue that workers should come ahead of G.M.’s robust profits and hefty share repurchases. However, the company’s stock price is only modestly higher than it was in 2010, when shares of the post-bankruptcy company began to be traded. And as painful as layoffs and plant closings are, it was a failure to see tougher times ahead that helped send G.M. off a cliff a decade ago.

Indeed, G.M. should be commended for its recent strategic decisions. Money-losing operations in Europe were sold. Its $581 million purchase of Cruise Automation was particularly prescient; that holding was recently valued at $14.6 billion after investments by SoftBank and Honda.

Autos are hardly the only part of the manufacturing sector facing challenges. Factory employment, which fell from 17 million jobs two decades ago to about 11.5 million in 2010, has regained only 1.3 million jobs during the post-2008 economic recovery. Just 434,000 of those jobs were added after Mr. Trump took office.

Yes, automation played some role in lowering employment, but the bigger problem has been competition from countries like China that are now able to produce goods as well as we do or better using much cheaper labor. For carmakers, that has meant moving production to Mexico.

In addition to lost jobs, the consequence of this competition has been lagging earnings for factory workers. Once paid a premium, manufacturing workers now earn below-average wages.

The president’s main policy response has been to start a trade war. Mr. Trump is correct that some countries — notably, China — don’t play fair, but his strategy has led only to acrimony, a jittery stock market and rising international tensions.

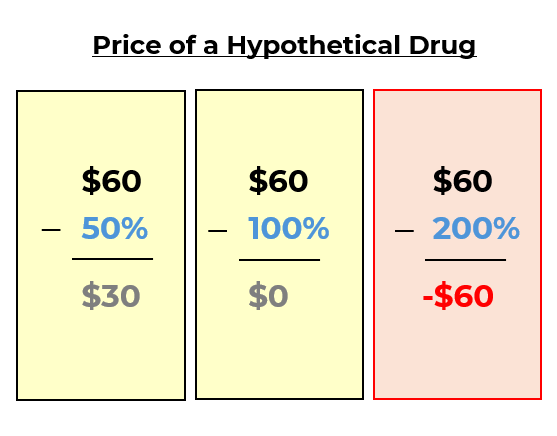

Even manufacturers don’t like the trade war. General Motors said that Mr. Trump’s tariffs on steel and other products would add $1 billion to its production costs, which puts more pressure on the company to cut workers.

Mr. Trump’s responses to G.M.’s decision also miss the mark. He called on G.M. to close one of its plants in China, even though G.M. doesn’t import a meaningful number of cars from there. He said G.M. should no longer have access to incentives to stimulate electric car production, which would simply damage the government’s effort to make the industry more competitive by spurring investment in new technologies.

Instead of Mr. Trump’s ham-handed approach to manufacturing, we should be pursuing more sophisticated remedies. I’m all for pushing back on the protectionist policies of China and other nations, but let’s do it with our allies and with the support of international organizations.

Similarly, while modernizing regulation is long overdue, simply throwing the rule book overboard, as Mr. Trump seems to be doing, is a mistake.

In addition, the American government should increase spending on education and training and finally begin that the long-delayed infrastructure initiative. We need to foster Americans’ pioneer spirit, and encourage them to move to where the jobs are.

For some Americans, it’s too late for retraining or relocation. They deserve a stronger social safety net, including programs to reduce the tendency to turn to alcohol and opioids.

We’re not going to return American manufacturing to its halcyon days, but we can do better. Sadly, Mr. Trump’s policies are taking us in the wrong direction.