Originally appeared in The NY Times.

Donald J. Trump spent much of his campaign peddling hope to beleaguered working-class Americans that, on his watch, those old-fashioned, good-paying manufacturing jobs would come back to America.

On Thursday, the president-elect was in Indiana to celebrate the news that the Carrier Corporation will move only 1,300 jobs to Mexico, not 2,100 as planned. That’s not bringing jobs back to the United States; they are just leaving more slowly.

Manufacturing employment in the United States peaked at 19.6 million in June 1979; today, 12.3 million Americans work in factories. Even during the economic recovery, amid proclamations of a renaissance in American manufacturing, production jobs barely grew. So far in 2016, they have fallen by 62,000, even as 1.8 million new jobs were created.

The lesson: You can’t fight a vast tide with a Twitter account.

To some degree, trade liberalization — including those deals that Mr. Trump and Bernie Sanders railed against — has encouraged countries like China to engage in anti-competitive practices. But the vast preponderance of American job losses has come simply because emerging-market countries have gotten much better at making stuff with workers earning far less.

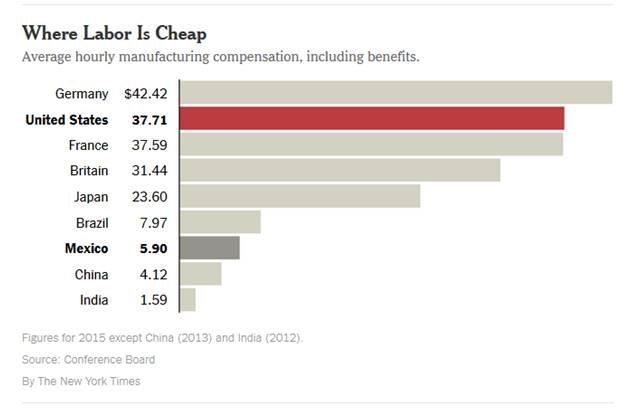

In 2015, a typical factory employee in the United States earned $37.71 an hour, including benefits; his Mexican counterpart received $5.90 an hour. And American executives say that the productivity that they get in Mexico is at least as good as what they get in the United States.

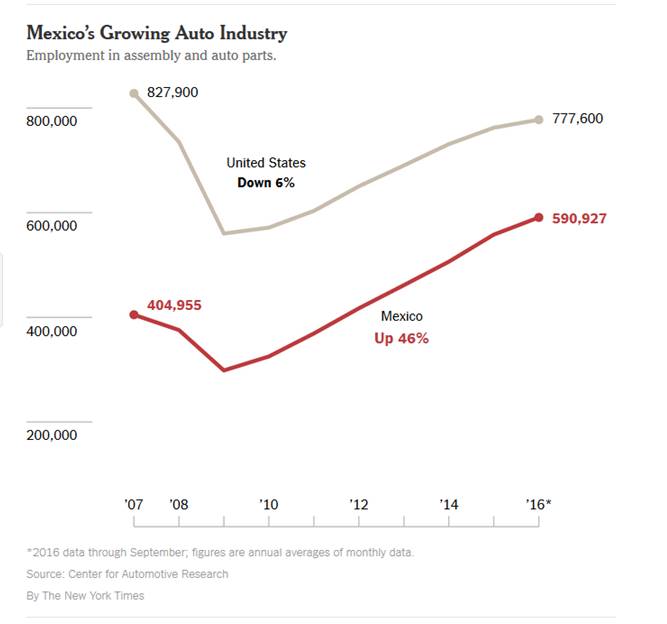

No wonder then that Mexico currently has a booming auto sector. Between 2007 and 2015, employment in the Mexican auto sector grew to 558,000 from 405,000, while auto jobs in the United States declined to 762,000 from 828,000.

Mr. Trump’s recent proclamation that he kept a Ford plant in Kentucky from closing was a mirage — Ford never planned to shutter the plant or eliminate any positions. More significantly, Ford is still going forward with the construction of a $1.6 billion facility in Mexico to assemble small cars, which cannot be done profitably using expensive American labor.

All told, Ford and General Motors plan to invest a combined $9.1 billion in Mexican facilities and hire 12,200 more workers over the next four years. By 2020, analysts project that about 40 percent of small cars sold by the Detroit automakers will be made in Mexico, more than double current levels.

Against that backdrop, I don’t see how the Carrier experience — even in its imperfect state — can be replicated.

For one thing, Carrier was apparently promised $7 million over 10 years in state tax incentives. It’s simply not realistic for Mr. Trump (or anyone) to run around the country subsidizing manufacturing jobs at high costs.

For another, Carrier’s parent corporation, United Technologies, garners about 10 percent of its revenues from Pentagon contracts, making the company particularly receptive to a president-elect.

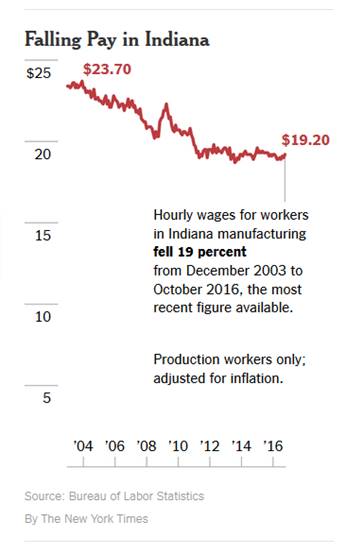

And, of course, Mr. Trump’s mouth-to-mouth combat can do little to address the equally important problem of wages. Thanks to pressure from low-wage countries, average hourly earnings for manufacturing workers in Indiana have dropped to $19.20 from $23.70 in 2003, after adjusting for inflation.

Beyond using political tactics, Mr. Trump wants to pursue his campaign agenda of renegotiating trade deals and imposing high tariffs once he has his hands on the levers of power. Higher import duties would hurt the very people Mr. Trump is trying to help. Thanks to trade, prices of many goods have fallen. In the decade between 2002 and 2012, the prices of toys dropped by 43 percent and those of furniture and bedding fell by 7 percent.

All told, one study of 40 countries found that if international trade ended, the wealthiest consumers would lose 28 percent of their purchasing power while those in the bottom tenth, who typically rely on more imported goods, would lose 63 percent. Sure, a small number of manufacturing jobs would return, but at an extraordinary price.

Let’s instead focus on a sensible economic plan to help those Trump voters who are hurting.

For starters, the president-elect is correct that more logical tax policies need to be pursued; our loophole-ridden corporate tax code encourages American companies to move abroad. And yes, some regulations hurt our competitiveness.

But his solutions (like huge tax cuts for the rich) smack of giveaways to capitalists rather than effective ways to help blue-collar workers in Michigan. More useful measures would be to raise the just 0.1 percent of our gross domestic product we spend on retraining workers, one-sixth of the average of other wealthy countries.

Mr. Trump’s priorities seem to be elsewhere; Republican plans to slash federal spending would reduce the help Washington gives struggling workers.

That highlights the conundrum of Trumponomics: He is offering an economic plan devoid of policies that would help the voters who elected him.