Originally appeared in the New York Times

A FEW days ago, I visited the shiny headquarters of the Peterson Institute for International Economics on “think tank row” in Washington — basically, the locker room of the Team Globalization and Free Trade cheering squad.

I was there to take part in a discussion of an old friend’s outstanding book on the subject, Steven R. Weisman’s “The Great Tradeoff: Confronting Moral Conflicts in the Era of Globalization.”

After praising Steve’s book, I emphasized that I had paid attention in economics class and understood that globalization incontrovertibly has benefited not only the world but also the United States. That’s in part because trade permits Americans to buy goods at lower prices; the added purchasing power helps our economy expand faster.

But I soon pivoted to my experience working in the Obama administration on the auto rescue, an experience that had seared into me the sense that intermingled among the many winners from globalization were a substantial number of losers.

So far, so good. Then I went rogue and uttered two blasphemous words: “Ross Perot.” He had a point, I said heretically, when he campaigned in 1992 against the landmark North American Free Trade Agreement, saying that it would result in a “giant sucking sound” of jobs headed south to Mexico.

A cool breeze drifted toward me.

As I looked out at my audience, I realized that the room was filled with winners — folks who, from all appearances, earned their livings from intellectual labor. Neither their jobs nor their wages were in jeopardy as countries ranging from Vietnam to Colombia became more competitive with us.

I pressed on.

Last year, according to the recent figures, our nation added 2.65 million new jobs. Just 30,000 of them were in manufacturing. So much for the widely trumpeted renaissance of Made in America.

At first glance, the automobile industry looks to be in better shape. From the depths of the crisis in 2009 through 2013, employment in the auto manufacturing sector in the United States rose by 23 percent, to 690,000 from 560,000.

That sounds pretty good, I said, except that employment in the Mexican auto sector rose to 589,000 from 368,000 during the same period, an increase of 60 percent. I’m happy that 221,000 more Mexicans got jobs, but let’s be honest: Absent open borders, many of those jobs would have been in America.

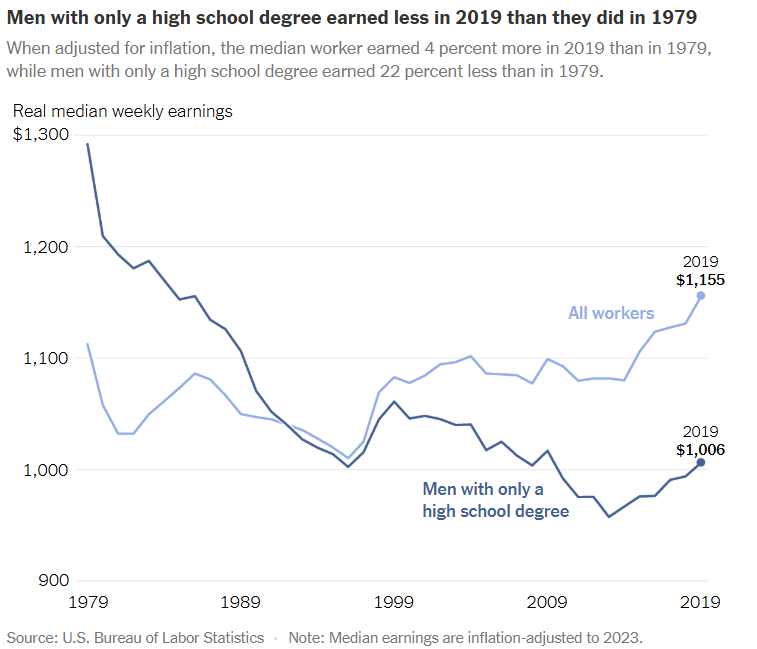

The wage picture looks even worse. Since January 2009, inflation-adjusted private sector wages across the economy have risen by 2.5 percent. In the fields of education, health and information, they are up by more than 3 percent. Meanwhile, in manufacturing, pay has fallen by 0.8 percent, and in the auto sector, by 12.7 percent.

“Last point,” I said to the 100 or so guests: Average manufacturing compensation costs (includes wages and benefits) in the United States in 2012 were $35.67 per hour; in Mexico, they were $6.36 per hour. “And American auto executives will tell you that the productivity they get in Mexico is at least as good as what they get in the United States.”

My central argument was not that we should close our borders or retreat from the world; it was that we need to be sensitive to the losers and try to help. The point — well illustrated in Steve’s book — is that globalization is not only an economic matter but also a moral one.

Presently, the institute’s blunt director, Adam Posen, used his final moments to shut me down, declaring that the “fetishization” of any industry was “immoral.” The problem of manufacturing is technology, he declared flatly.

Blaming technology is a common refrain from economists who hate the thought that globalization is not the world’s unambiguous salvation.

Sorry, Adam, I thought silently, having been afforded no time to respond. If technology were the source of manufacturing workers’ woes, productivity would be rising sharply, which it surely isn’t (notwithstanding claims by some economists that official statistics have been understating efficiency gains).

“Don’t blame the robots for lost manufacturing jobs,” read the headline in a blog post last spring by two scholars at the venerable Brookings Institution.

I have never forgotten a powerful article I read in Foreign Affairs in 2007 that called for huge tax redistribution, both as a moral matter and as a mechanism for ensuring political support for free trade. (The authors were hardly left-wing shills — one had served in the administration of President George W. Bush.)

That still sounds like the right idea to me.

It’s not only morally wrong to fail to help those on the losing end of globalization, but it will also end badly politically, as the ascendant candidacy of Donald J. Trump illustrates.