New jobs figures released on Tuesday morning paint a potentially worrisome picture of the employment sector, with unemployment rising and the number of new jobs at low levels. Why has this been happening in an economy that is still growing? A range of reasons, from the Trump tariffs to artificial intelligence to general belt-tightening by business.

The unemployment rate rose to 4.6% in November, up from a low of 3.4% in April 2023. As recently as January, when Donald Trump assumed the presidency for the second time, it was 4%. Even more concerning, the jobless rate among young Americans (ages 16 to 24) who were looking for work, continued its rise, to 10.6% from 9% in January. That’s the highest it’s been since December 2016 (excluding covid). Similarly, unemployment among Black Americans reached 8.3%, compared to 6.2% in January. Black and young Americans are among those considered “marginal workers,” meaning that they are often last to be hired and first to be fired.

Meanwhile, the economy added 64,000 new jobs in November. That brings the average since April to 17,000 jobs a month. But Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell said last week that his economists believe that payroll growth may have been overstated by about 60,000 jobs a month. If so, that would mean the economy has actually been losing jobs, potentially more than 40,000 a month since April. In contrast, before Covid, the economy was adding almost 170,000 jobs a month.

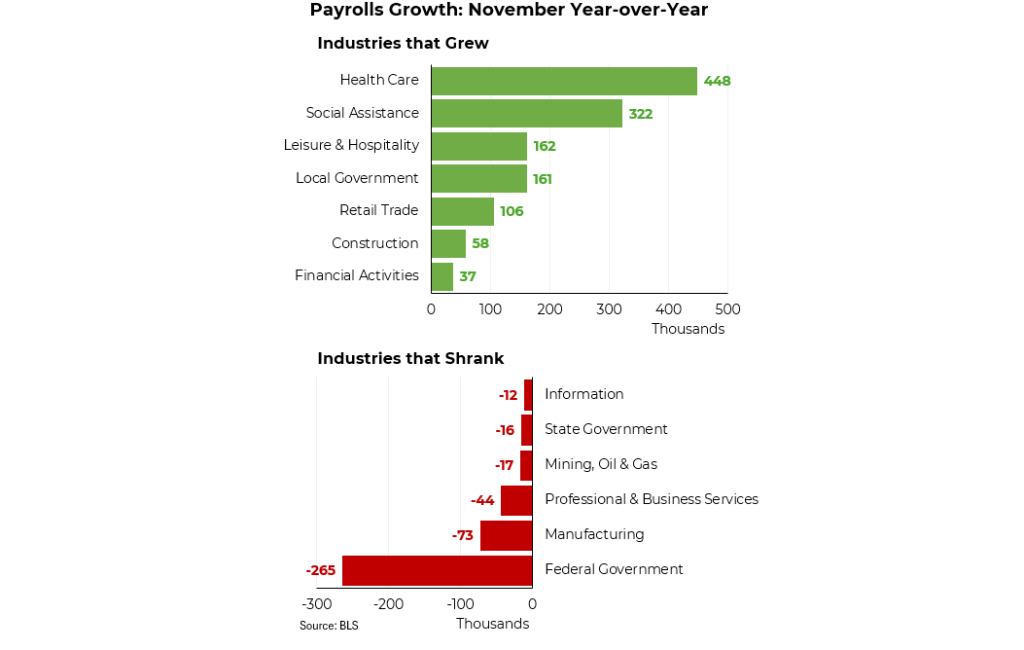

Over the past year, the biggest source of new jobs — by a wide margin — has been healthcare, a total of 448,000 jobs. New social assistance jobs (taking care of the elderly, children, and other people in need) totaled 322,000, followed by leisure & hospitality and local government. On the other end of the spectrum, the biggest job losses came — perhaps not surprisingly — from the federal government. But manufacturing, a focus of President Trump’s, lost 73,000 jobs.

Another disappointing sign is the still elevated number of long-term unemployed. Nearly 25% of those out of work have been jobless for 27 weeks or more, the highest level since 2017 excluding covid. The “underemployment rate” — the number of people working part-time but eager to work full time — has also been increasing.

The persistence of long-term unemployment has led many to worry that the advent of artificial intelligence could mean a long period of high unemployment. That might be so, but there has not been a technological innovation in history that has ultimately not led to more jobs than it cost. And we have a number of sectors with promising employment prospects, ranging from health care to technology to traditional occupations like construction.