President Donald Trump’s new tariffs sent markets into a tailspin, just the latest in a series of actions by his administration that have caused economists to raise their expectations for inflation and cut their projections for growth. A vast majority of economists believe tariffs are counterproductive and there is considerable historical evidence to support their view.

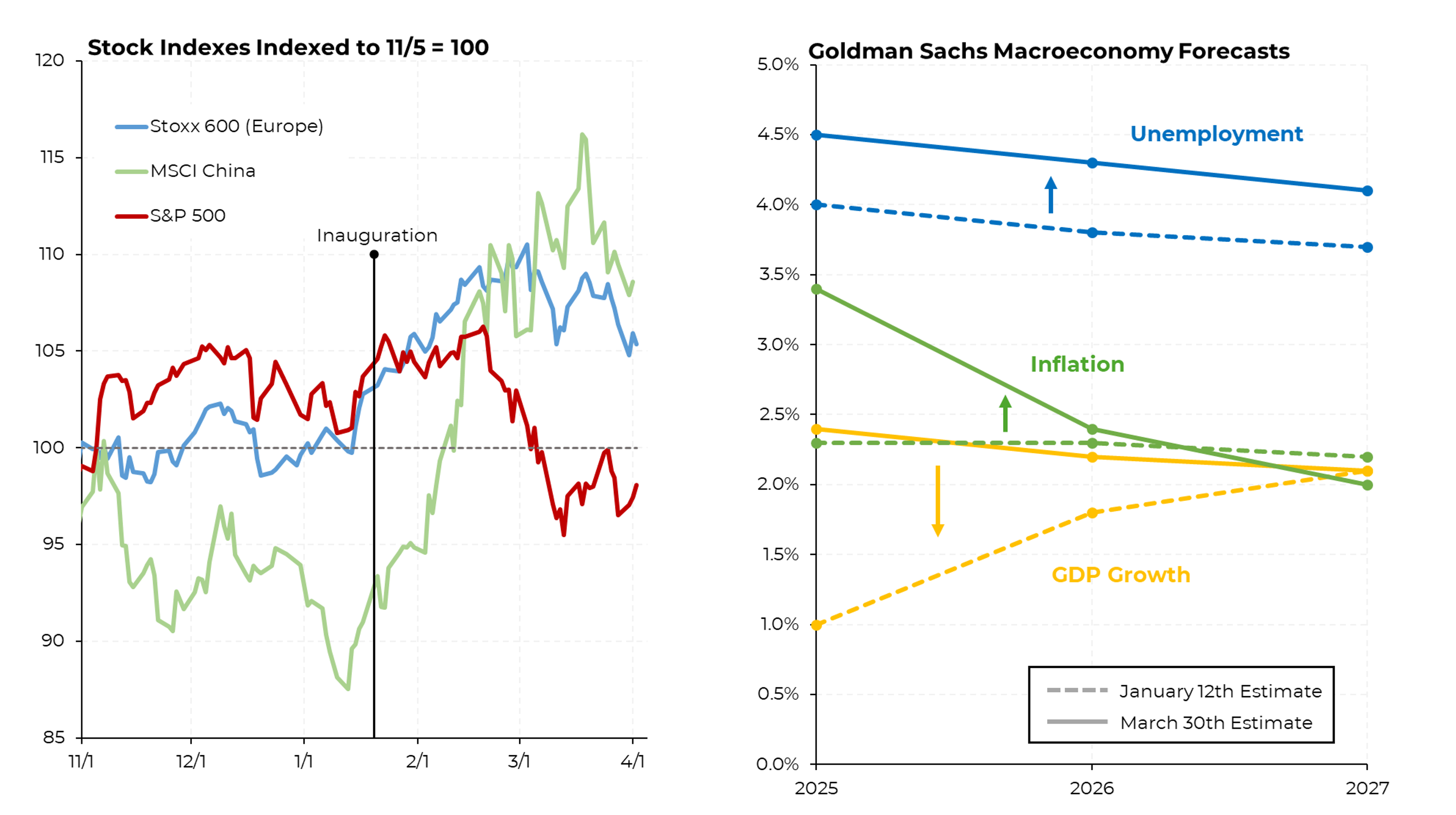

Even before the market’s late day swoon, it had already given up all of its post-election gains, as investors grew concerned about the Trump economic program, particularly with regard to trade. Indeed, for the first time in many years, the U.S. market has not only performed poorly, but it has gone down while share prices in Europe and China have risen significantly. All told, our stock market — whose strong performance during Trump 1.0 was a great satisfaction to the president, is now down more than 6% since election day (and not including Wednesday’s aftermarket activity).

Even before Trump’s announcement, economists have been downgrading their forecasts, partly in anticipation of new tariffs but also because the economic uncertainty around Trump’s policies have caused both consumers and businesses to pull back. Goldman Sachs, for example, lowered its projection for 2025 gross domestic product to a 1% increase while inflation is likely to accelerate to 3.4%, constituting stagflation. Projections like this one from Goldman Sachs are surely to be degraded in coming days. And also prior to Wednesday’s announcement, firms have been raising their probabilities of a recession: On Sunday, Goldman increased its to 35% from 20%.

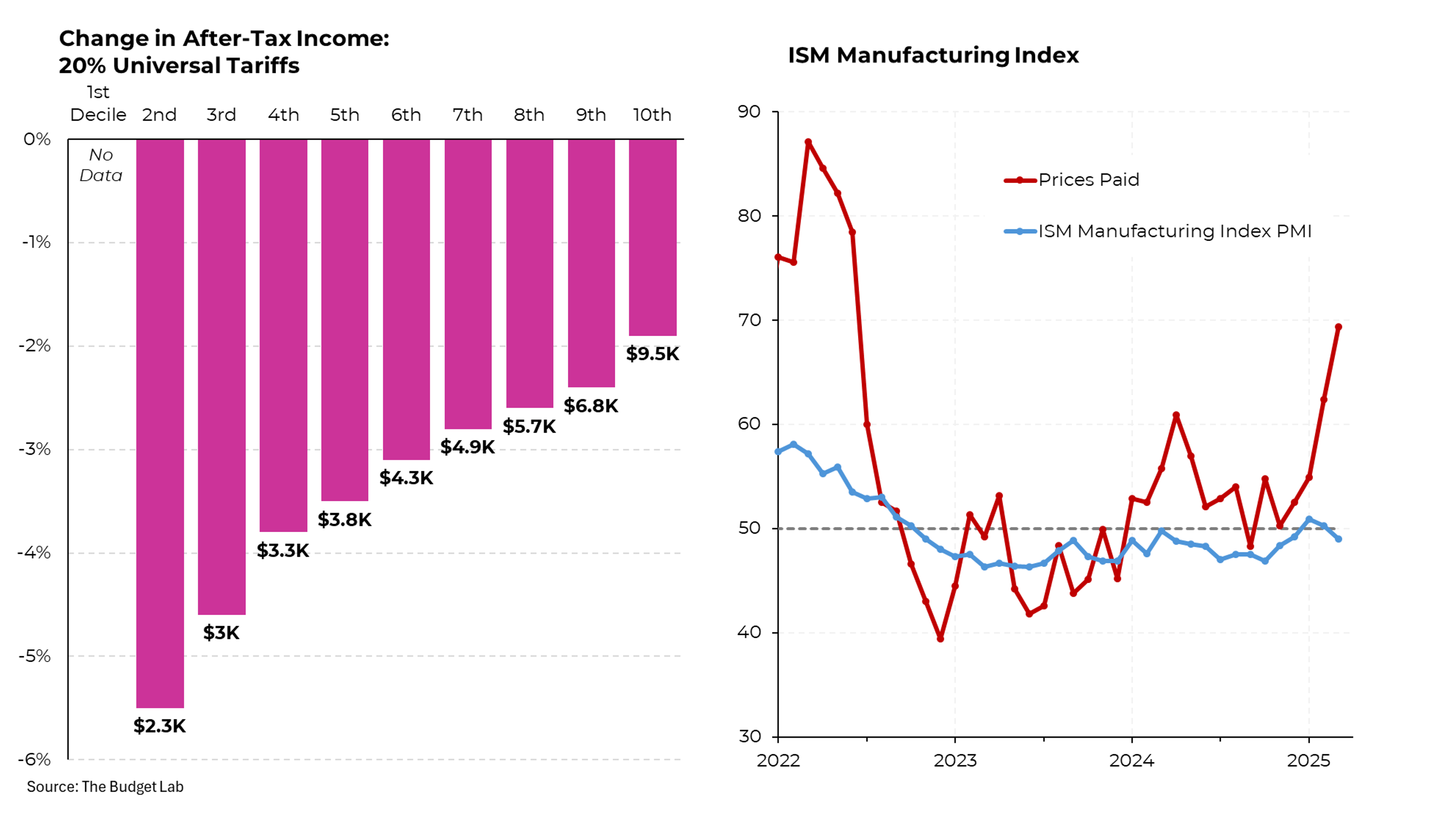

While we also don’t have new forecasts for the impact of this on consumers, estimates of earlier possible packages shed light on the possible impact. A study by the Yale Budget Lab of a 20% universal tariff found that it would cost the average American about $4,000 a year — and the tariffs announced today will almost surely cause this estimate to rise. In addition, the tariffs hit different income groups suffering disproportionately, with incomes hit most in percentage terms for those closer to the bottom.

Business has already begun feeling the impact of the tariffs that have been put in place and those that have been anticipated. A recent survey of purchasing managers found that prices being paid for supplies and raw materials are now rising at the highest levels since the post-Covid inflationary environment. (Meanwhile, manufacturing production has already been contracting.)

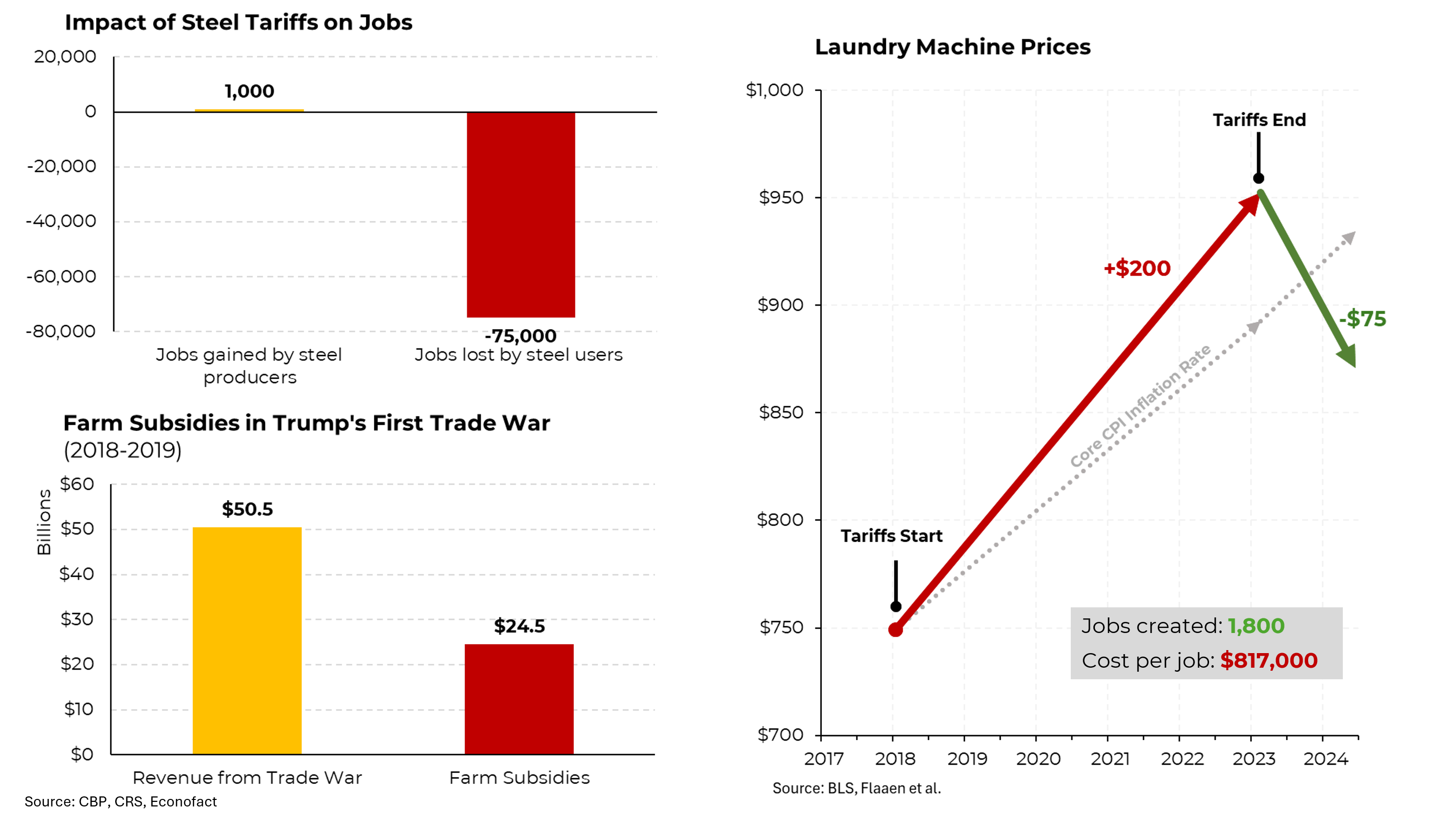

The history of Trump’s tariffs during his first term — far smaller and more targeted than these — provide lessons in why tariffs don’t work. Take, for example, his tariffs on steel (25%) and aluminum (10%). According to an analysis by economists and Harvard and UC Davis, the tariffs led to only 1,000 jobs while industries that use steel and aluminum — producers of cars, appliances and much more — lost 75,000 jobs.

Then when Trump put a range of tariffs on certain imports from China, that country retaliated by putting tariffs on farm products that we export to them. To help farmers, Trump provided $24.5 billion in aid to them, almost exactly half of the $50.5 billion in tariffs that he collected between 2018 and 2019.

Laundry equipment is another example of tariff policy hurting rather than helping. Tariffs imposed by Trump in January 2018 caused the price of laundry equipment to rise by $200. But when President Biden didn’t renew them, prices of that equipment fell by $75. On study found that during the first several months of the tariffs, firms raised the price of dryers in tandem with washers even though they were not subject to the tariffs. They also found that the tariffs created 1,800 jobs but cost $817,000 per job.