On Thursday, the House passed the Senate’s version of the overall budget framework that will help determine the outcome of the efforts by President Trump and Republican legislators to implement their plans for tax and spending reductions. It is a radical agenda that at the least, will add trillions of dollars to the national debt and could also lead to cuts in spending programs, including some aimed at the less privileged.

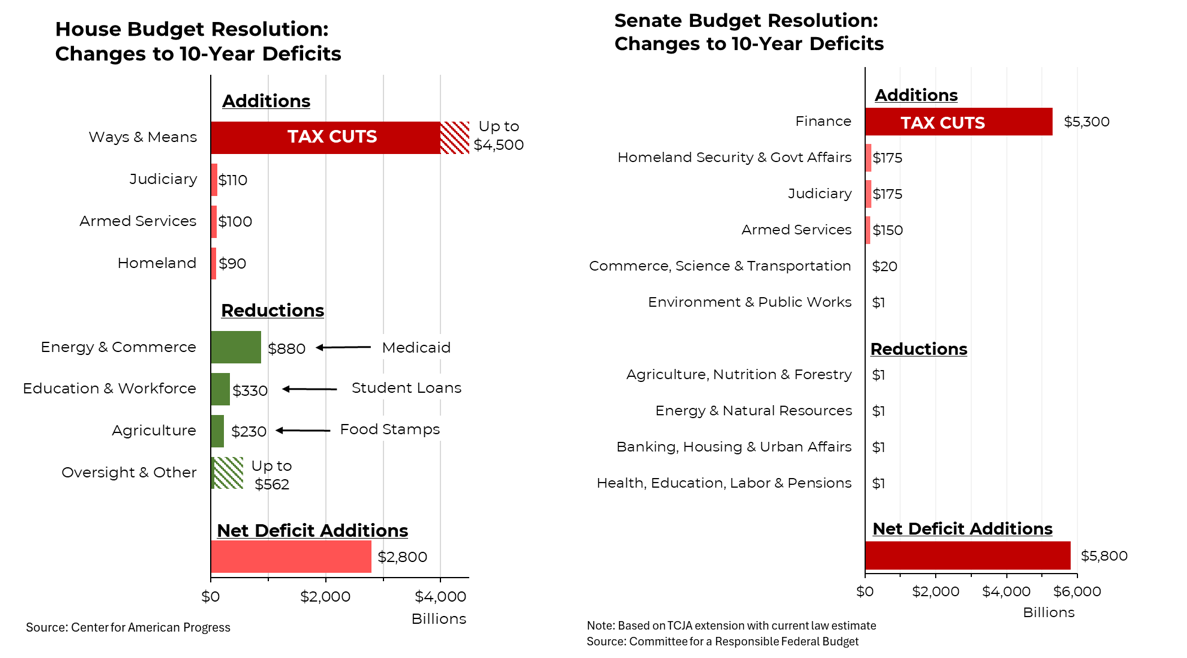

The budget setting process achieved its first milestone in February when the House of Representatives passed its version of a budget resolution, legislation that would make permanent the individual tax cuts passed in 2017. That bill, which included up to $2 trillion of spending cuts to programs including Medicaid and food stamps, would have added up to $2.8 trillion to the deficit and debt over the coming decade. (That would be on top of the $7.9 trillion of new debt already likely to be incurred.)

The Senate, however, went even further, incorporating more tax cuts ($5.3 trillion) and less spending reduction into its plan, for an overall addition to the deficit of $5.8 trillion. Notably, the Senate bill includes $521 billion of new spending, mostly for homeland security, the judiciary and defense, and just $4 billion of spending reduction. And now, at least for the moment, the Senate version has prevailed (although Senate Republican leaders gave vague assurances that they would find spending reductions later.)

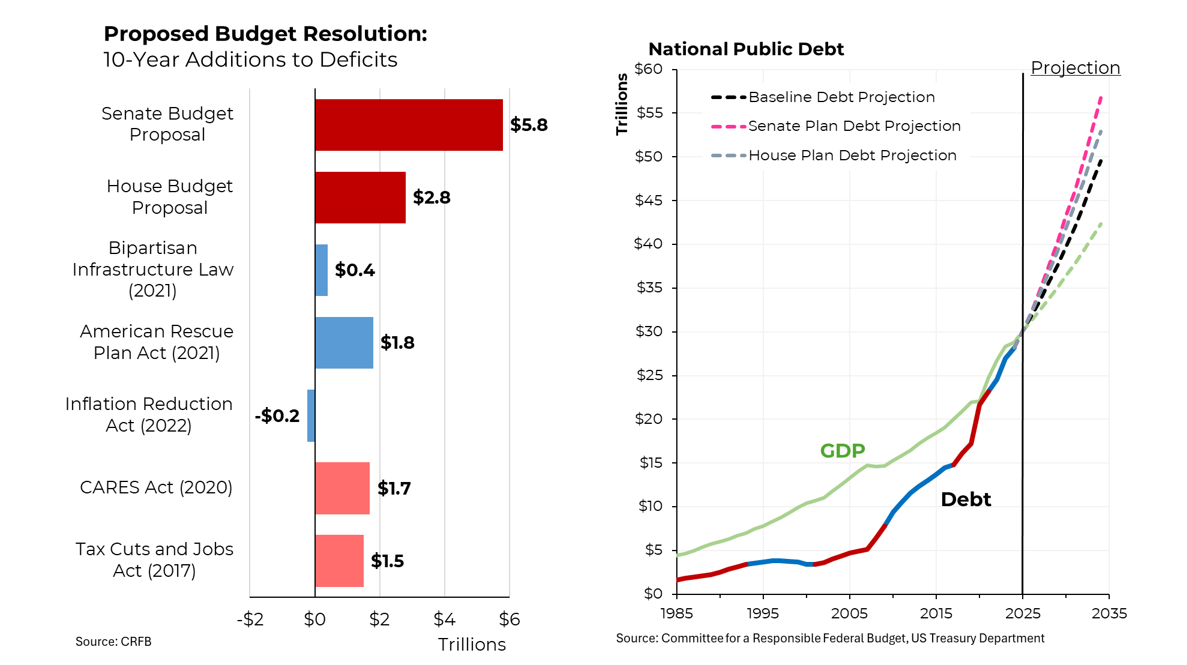

Both the House and the Senate versions dwarf any deficit-busting legislation passed in memory. The Senate package, for example, adds more to the deficit (and debt) than the last five major pieces of spending legislation combined. It dwarfs the $2 trillion of additional deficits created by the three major pieces of legislation passed under President Joe Biden.

While our debt is already climbing rapidly, either of these packages would exacerbate the problem. We have almost $30 trillion of debt held by the public at the moment, roughly equal to the size of our economy. Under the Senate plan, the amount of debt held by the public would rise to $57 trillion by 2034, representing 134% of the size of our economy. Importantly, in addition to all this debt, we have $73.2 trillion of unfunded obligations over the next 75 years at their present value to Medicare and Social Security recipients.

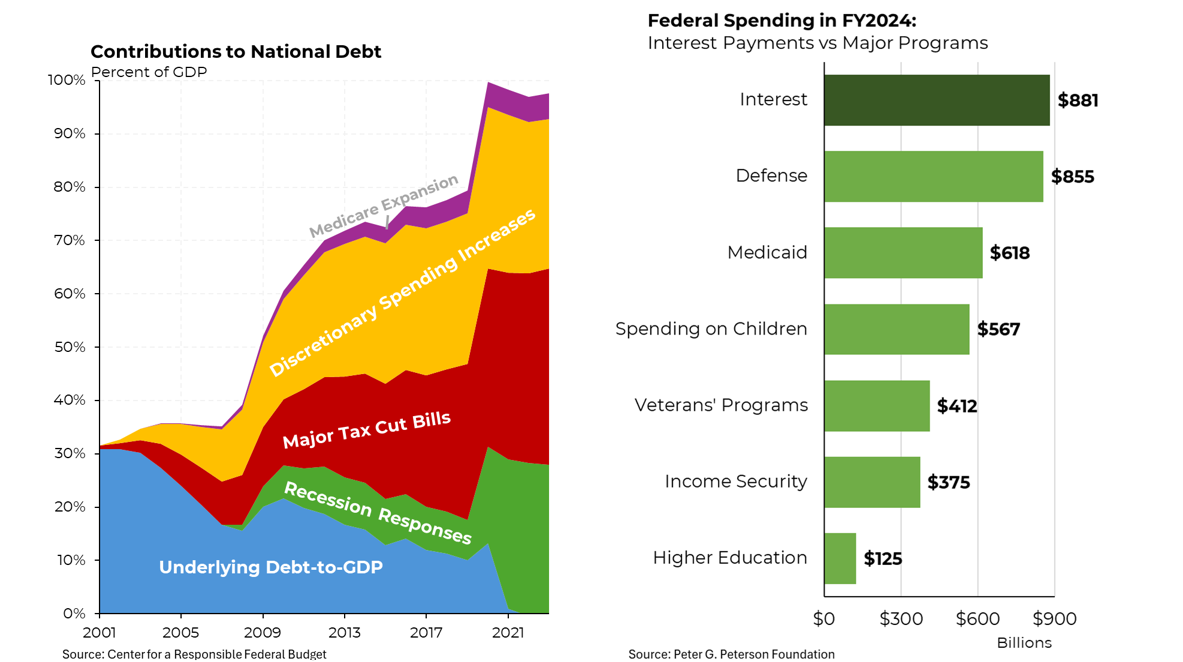

We did not need to be in this position. According to calculations by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, if we had maintained reasonable fiscal discipline over the 2 ½ decades since 2001, we could potentially have little to no debt now. Instead, we implemented repeated tax cuts and we increased discretionary spending far faster than the rate of inflation and growth of our economy. In fairness, some of that increase in discretionary spending went for defense and we also spent heavily following the financial crisis and following the outbreak of the Covid pandemic.

But because we amassed all that debt, interest expense now exceeds defense spending (and every other category of spending) for the first time in memory. That raises the specter of Ferguson’s Law, a 17th century theory that says that when a great power’s interest expense exceeds its defense spending, it risks becoming a lesser power. The UK’s “appeasement” strategy toward Germany in the 1930s and the 17th century decline of the Spanish empire are instructive examples of the perils of excess debt. And with interest rates rising, the cost of servicing our debt will become that much greater.