The latest inflation readings arrived and the news was not good, raising questions about the future direction of interest rates.

Meanwhile, on a lighter note, the new administration got one policy move right: It announced that it would no longer mint pennies.

Instead of ticking downward, the key inflation indicator instead ticked upward. Prices for all items except the volatile categories of food and energy rose by 3.3% over the prior year, the highest reading since May 2024. On a month-to-month basis, the results represented the largest increase since August 2023. Among the more noteworthy items was a 53% increase in the price of eggs, a consequence of the avian flu that has been sweeping the country. At the other end, energy, groceries and apparel all showed smaller than average increases over the prior year.

The disappointing inflation news over several months — combined with President Trump’s tariff plans — has caused Americans to sharply revise upward their expectations of future inflation. In January, they expected inflation in the coming year to total 3.3%; now they are anticipating that prices will rise by 4.3%. Expectations have not been this high since November 2023.

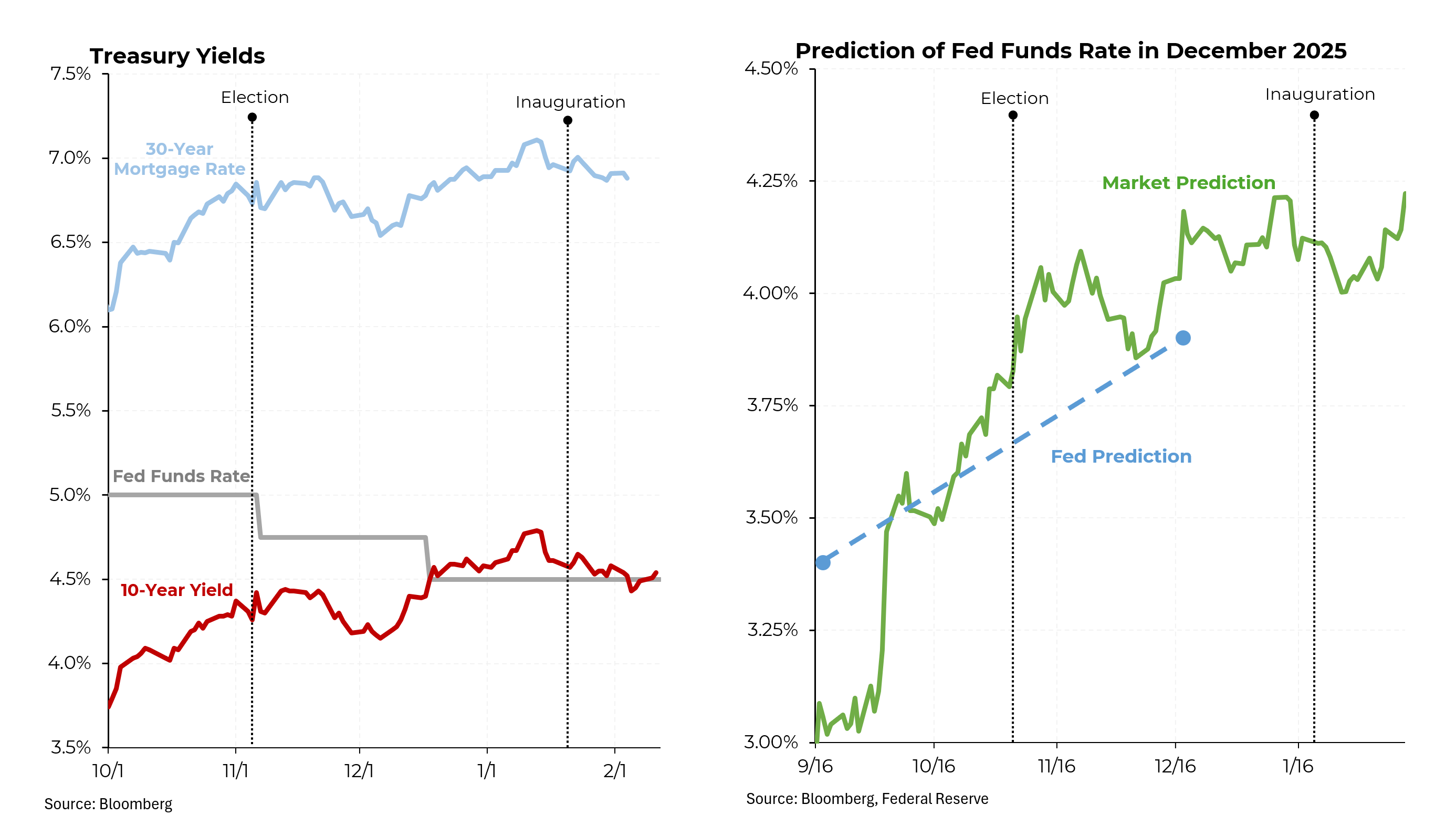

While the Federal Reserve has been cutting short-term interest rates, the disappointing recent inflation results have caused longer term interest rates to rise. Those rates — like the 10-year Treasury rate and the 30-year mortgage rate — move more in tandem with inflationary expectations. All told, the 10-year Treasury rate has risen to 4.6% from 4.3% On election day.

The tough news on inflation has caused expectations for future interest rate reductions to moderate. Just before the election, the market expected the Fed to reduce interest rates to 3.8% by the end of this year. Now it anticipates only a reduction of 0.25% to 0.5% over the course of this year. (Fed chairman Jerome Powell seemed to confirm this in remarks earlier this week.)

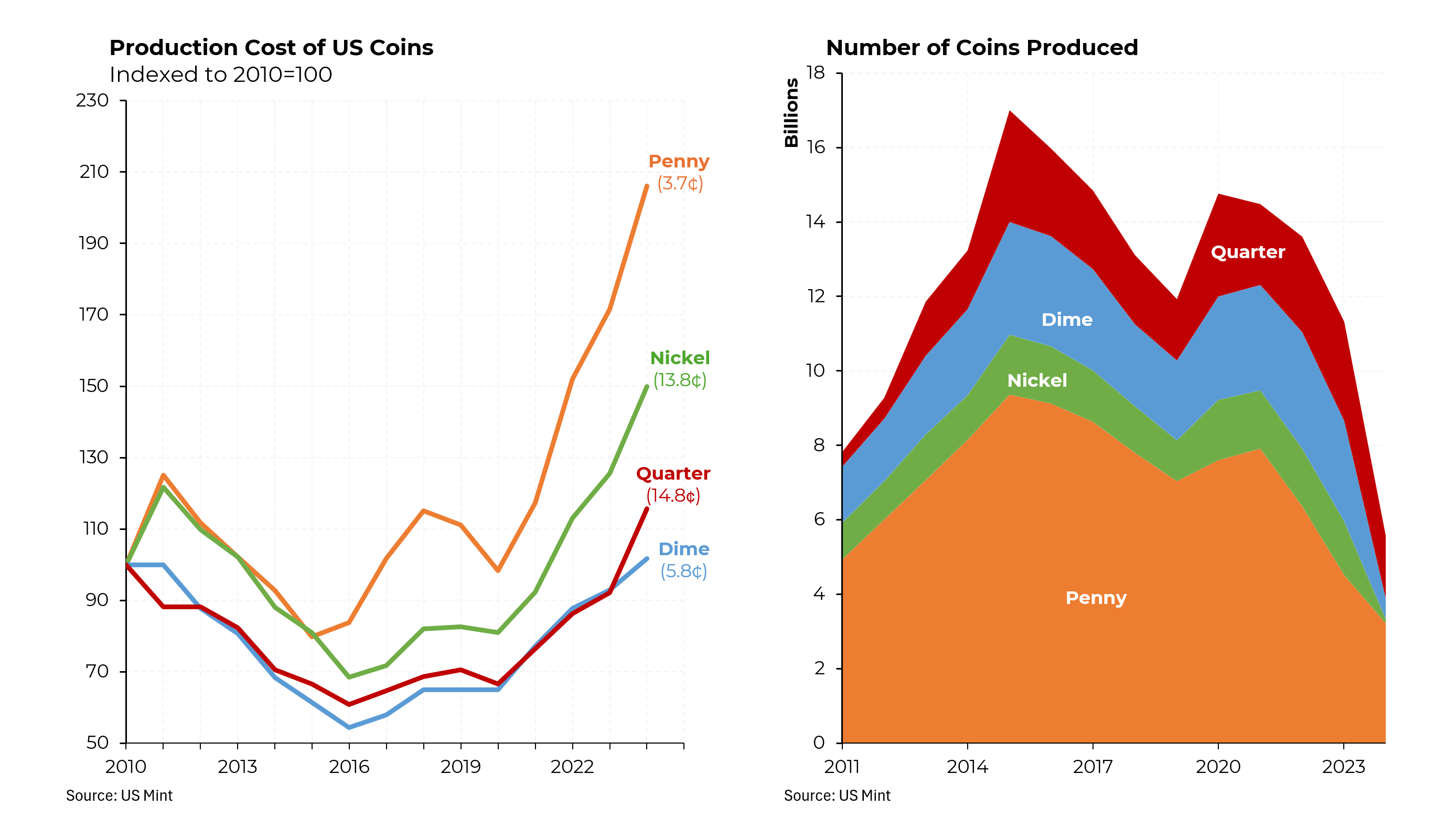

Meanwhile, President Trump made at least one good decision: He announced that the U.S. mint would cease production of the penny. The cost of minting coins has, of course, been rising and now it costs 3.7 cents to make a penny. And as inflation has raised the price of all transactions, the need for such small denomination coins has dropped. (It’s also worth noting that the cost of making a nickel has soared to 13.8 cents so that’s also a bad deal for the Treasury.

Not surprisingly, the number of coins being produced has dropped, both because the government loses money on more than half of them and also because as more and more transactions occur electronically, Americans have less use for coins.

Why has it taken us so long to make such an obvious move? Concerns that eliminating the penny would add to inflation if businesses chose to round up every transaction that would have required pennies. But other countries, such as Australia and Canada, eliminated pennies years ago so it is a belatedly good move by the United States.