In an interview Tuesday at the Economic Club of Chicago, Donald Trump pronounced “tariff” to be the “most beautiful word in the dictionary.” Unfortunately, the vast majority of economists would doubtless proclaim “tariff” to be among their least favorite words in the economic lexicon.

Trump’s somewhat tempestuous hour-long session was replete with other falsehoods, such as claiming that the tariffs he imposed on China during his presidency had delivered “hundreds of billions of dollars” to our Treasury. (The actual number — from all Trump tariffs, not just on China — is less than $89 billion.)

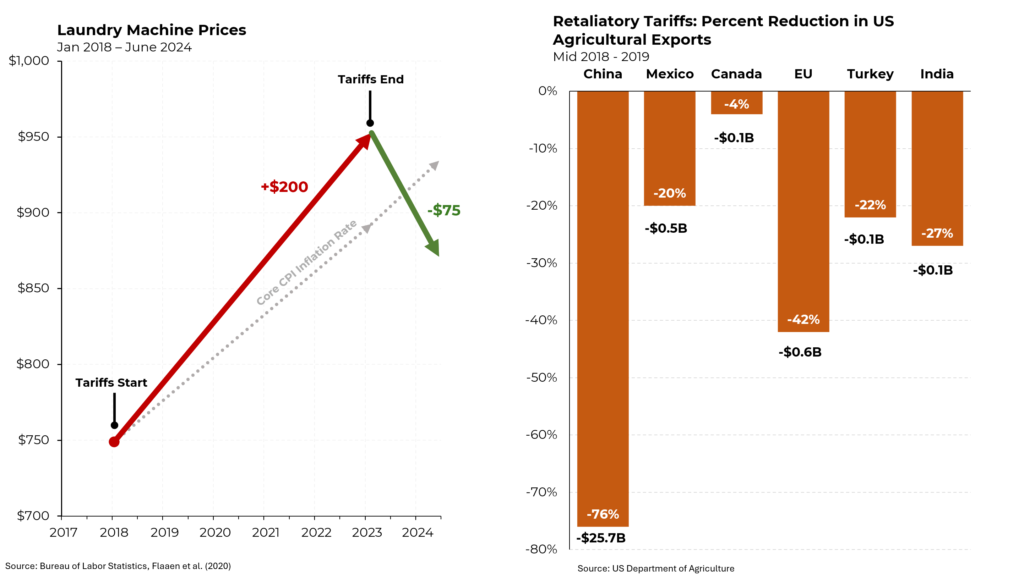

Among the reasons to not like tariffs is that they function as a kind of national sales tax, raising the price of goods that consumers (and businesses) purchase. But don’t take my word for it; here’s a real life example. In January 2018, Trump imposed tariffs on imported washing machines. Over the ensuing five years, average laundry equipment prices rose by $200, a 27% increase during a period when “core prices” rose by 19%. Then, when President Joe Biden allowed the tariffs to expire, washing machine prices fell by $75, bringing their overall increase to less than the rise in other costs.

Moreover, a study found that in the first several months after the tariffs were imposed, firms raised the price of dryers in tandem with washing machines, even though dryers were not subject to the tariffs. The study also found that while the tariffs created 1,800 jobs, each job cost consumers about $817,000.

When we impose tariffs, other countries often retaliate. From mid-2018 through 2019, in response to tariffs that Trump imposed on steel and aluminum, a number of countries and the European Union, put tariffs in place on some of our agricultural exports. Farmers lost $27.2 billion in exports and Trump was pressured into increasing farm aid to partially compensate.

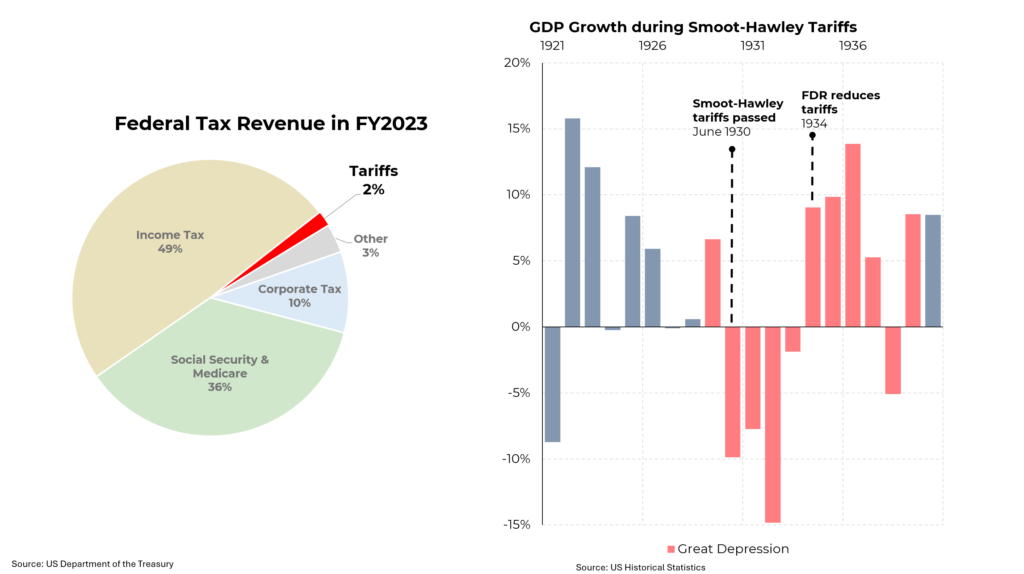

Against that backdrop, it shouldn’t be surprising that tariffs have been kept by successive presidents to just a small sliver of federal revenues — less than 2% at present.

Tariffs not only raise costs for consumers, they slow economic growth. (A basic principal of economics is that increased trade can aid prosperity by allowing countries to specialize on producing what they can manufacture or grow most efficiently.) The classic textbook example of the damage that tariffs can do were the Smoot-Hawley tariffs of 1930. They didn’t cause the Great Depression but economists almost universally believe that they exacerbated it as our trade with Europe — then our principal trading partner — fell by two-thirds. And then, after they were removed in 1934, our recovery accelerated.

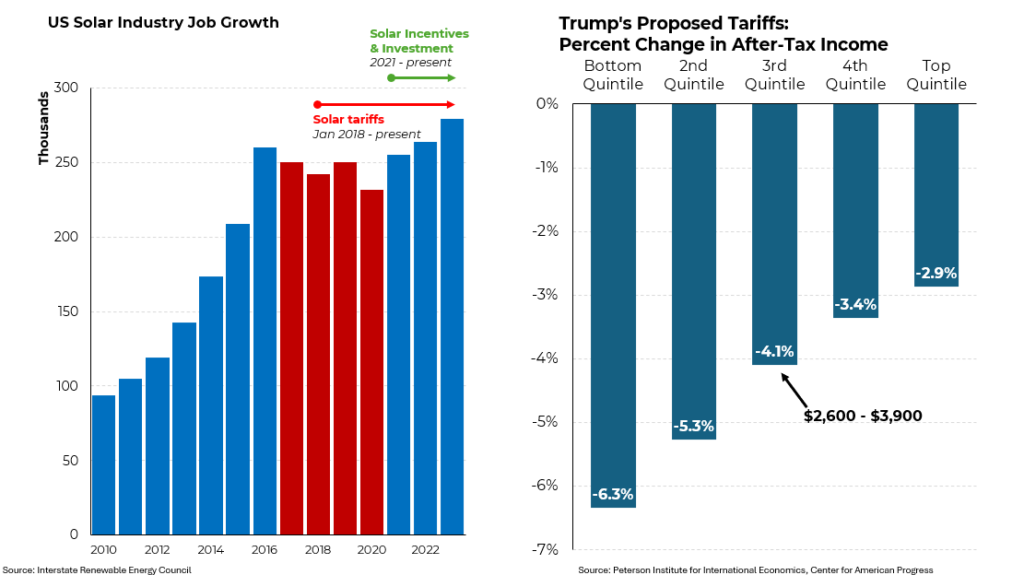

Tariffs are also regressive, meaning that they hurt those at the bottom proportionally more than those at the top. After Trump imposed tariffs on solar panels, job growth in the solar panel industry fell to 232,000 in 2020 from 260,000 in 2016. (After the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, the number of jobs in the solar industry rose to 279,000.)

Looking ahead, a study by the Peterson Institute for International Economics concluded that Trump’s plan for new tariffs would cost the typical household between $2,600 and $3,900, with those near the bottom losing a significantly higher share of their after-tax income than those at the top.