The 2024 baseball seasons has begun – a good moment for a look back at the impact of changes made a year ago to try to refresh the nation’s pastime, which has been losing fan attention to other major sports, particularly football.

To the less knowledgeable, the rules changes may seem modest. Pitchers were given time limits between throws. The size of the bases was made slightly larger. Pitchers no longer bat in either league. And new limits were imposed on how fielders could be positioned.

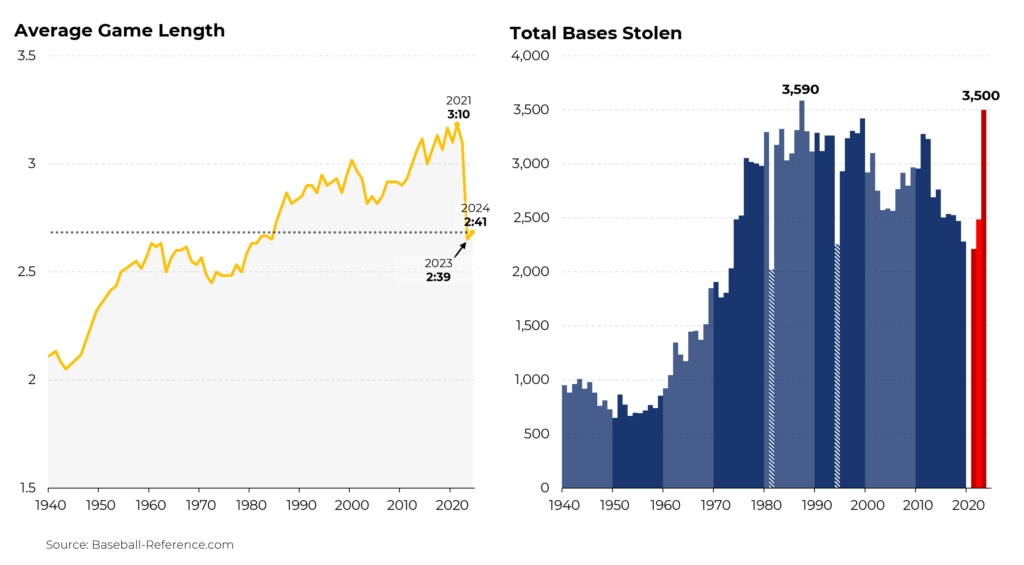

The results were noticeable. The average game length dropped by 27 minutes, to 2 hours and 39 minutes, the same as it was in 1984. (Although note that games were generally even shorter before 1984.) The larger bases led to a jump in stolen bases, up to 3,500, just shy of the record 3,585 set in 1987. The new limits on player positioning also had an impact – batting averages ticked up from 0.243 to 0.248, the same level as 2018. (That’s still well below the all-time high of 0.271 set in 1999.)

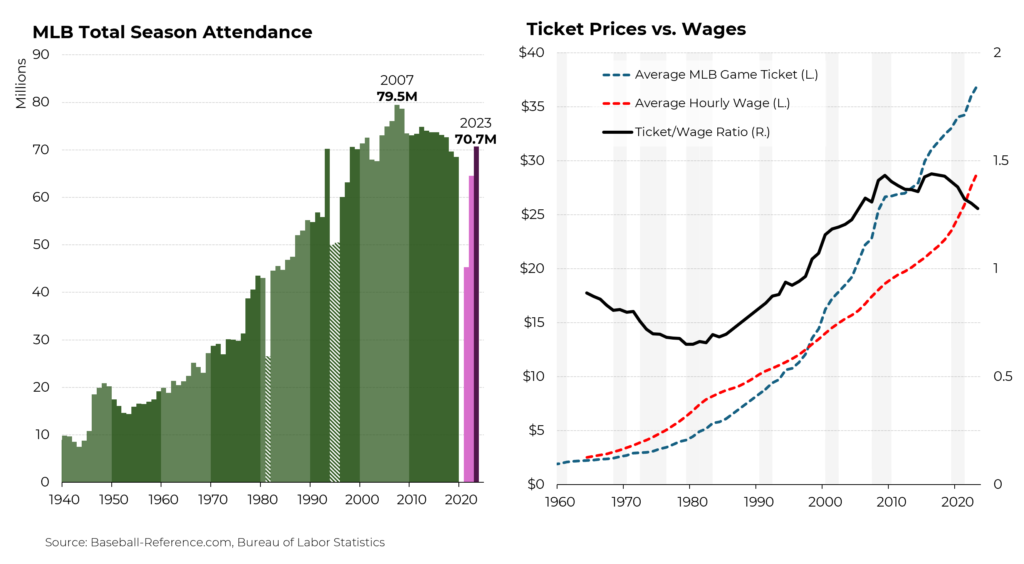

It’s not hard to find the motivation for the changes. Total attendance peaked in 2007, right before the financial crisis and entered a steady decline (muddled a bit by Covid). That is even worse than it appears because the U.S. population is up by more than 10% since 2007.

Interestingly, the attendance problem was not lost on the teams, which responded by moderating the pace of ticket price increases. While ticket prices continued to rise in dollar terms, they have been falling in relation to wages, back to where they were roughly 20 years ago. Perhaps in part as a result, attendance last year reached the highest level since 2017.

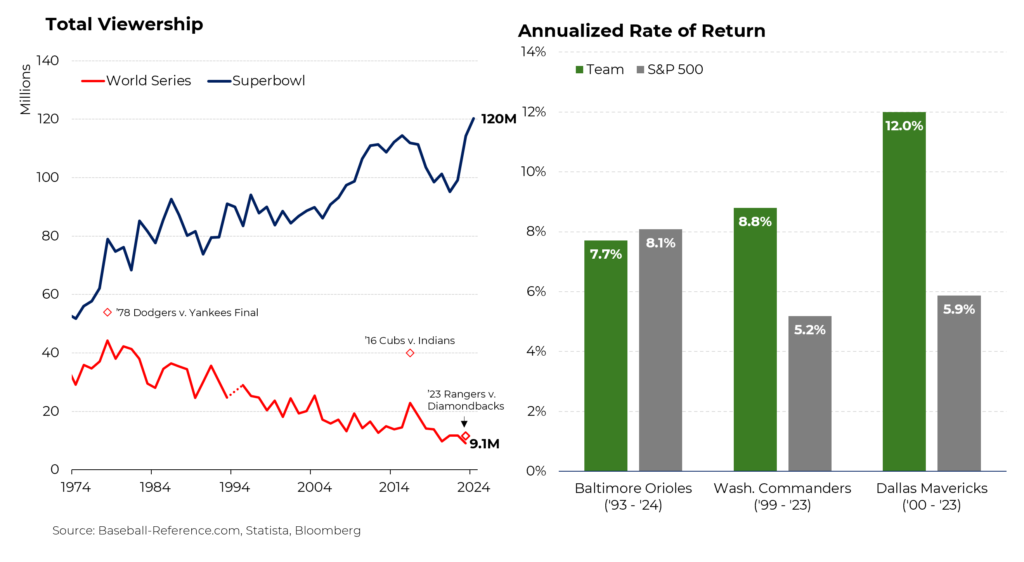

Another measure of baseball’s lost ground is the divergence in viewership between the World Series and the Superbowl. In 1974, the average viewership of a World Series game was about 60% of that of the Superbowl and the final game attracted almost as many viewers as the Superbowl. Last year, that figure is less than 10% and viewership barely ticked up in the final game.

All of this appears to have had some impact on the financial rewards of owning a baseball team. The Baltimore Orioles are being sold to a group led by financier David Rubenstein for $1.725 billion, compared to the $173 million paid by the prior owner, Peter Angelos, in 1993. That sounds great except that an investor would have done better in the stock market. By contrast, Daniel Snyder, the much-reviled former owner of the Washington Commanders football team, did far better than the stock market over his 24 years of ownership. And Mark Cuban did even better while owning the Dallas Mavericks for 23 years.