Today is Earth Day – no better a time to review the destruction we are wreaking on our planet by emitting carbon dioxide in extraordinary and unrelenting quantities. And yes, some progress has been made in bending the curve of how much is being sent skyward, but that progress is not nearly enough to give us much reason for hope or optimism.

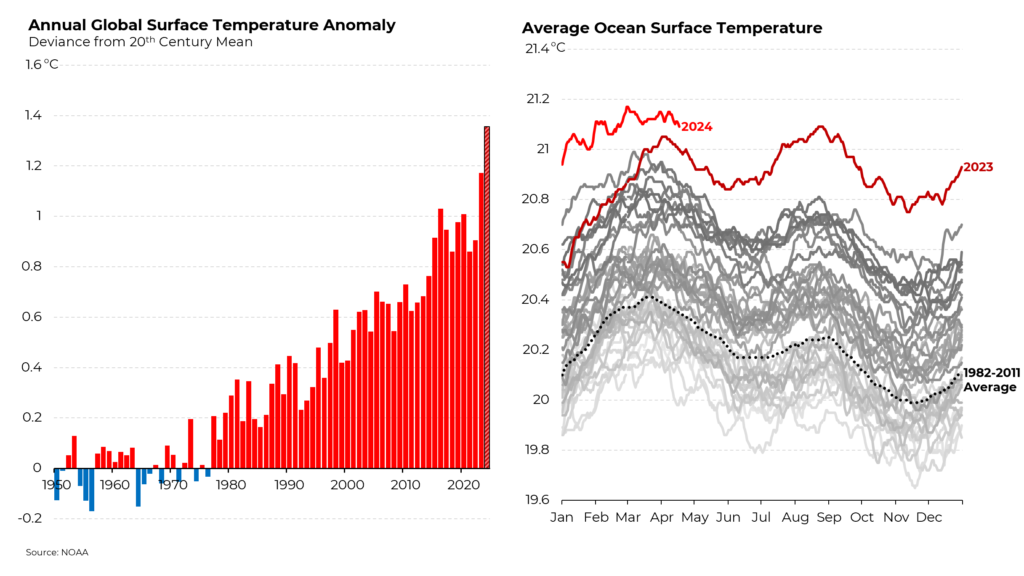

By now, even the most ardent climate change deniers have to admit that something terrifying is happening: Surface temperatures have soared to record levels and if anything, the rate of increase may even be accelerating. Thus far, 2024 has been a record 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than the 20th century average, hotter than last year’s 2.2-degree record. In just two years, the average yearly temperature has risen by 0.8 degrees Fahrenheit. Whether increases of that magnitude will continue remains to be seen but it is a fact that we have not had a below-average year since 1976. What has caused this? The simple answer is that more carbon dioxide traps more heat for the sun (which is why we talk about “greenhouse gases”). Currently, our atmosphere contains 416 parts of CO2 per million; in the past 650,000 years, the concentration hadn’t crossed 300 until recently.

Among the many deleterious effects of rising air temperatures are rising sea levels, as higher temperatures melt ice around the poles and elsewhere. Since 1979, Arctic sea ice loss has totaled 649,000 square miles, roughly equivalent to the size of the state of Alaska. An even larger amount of sea ice has been lost in Antarctica. That has raised sea levels, threatening coastal communities, particularly through the increase in the number of extreme weather events like hurricanes (the prevalence of which is correlated with higher global temperatures). Higher sea temperatures have a variety of negative effects on marine life, from bleaching coral to literally causing fish to suffocate because warmer water doesn’t hold as much oxygen as colder water.

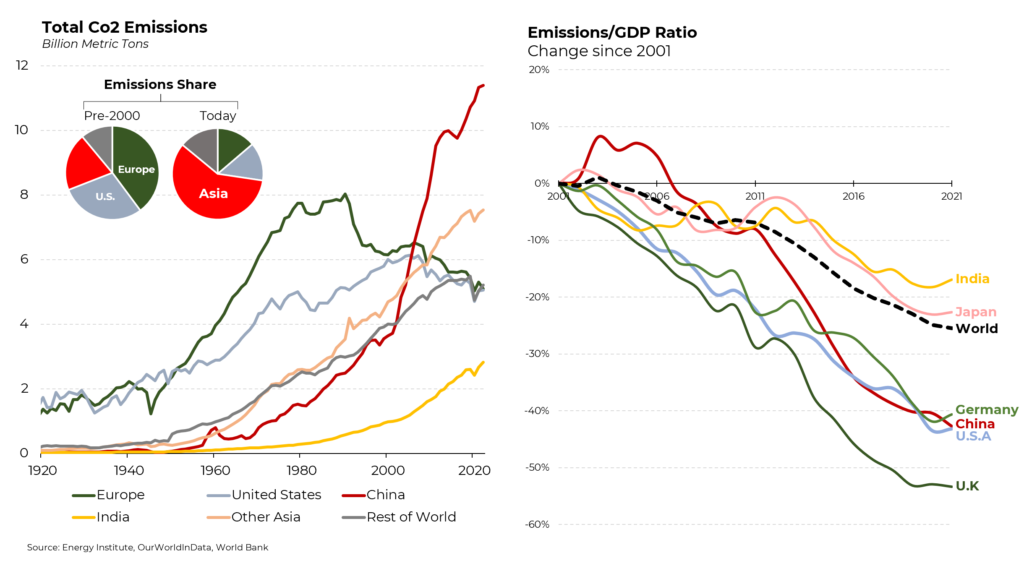

While the problem of carbon dioxide emissions and global warming has been known for decades, only limited progress has been made in addressing the issue. The amount of carbon dioxide being emitted has continued to rise (although at a slower pace than before). That’s because progress made in the developed world – principally by Europe but, more recently, by the United States – has been more than offset by the increase in emissions by developing countries, particularly China and India.

It’s not that India and, particularly, China have not made some efforts to curb their CO2 emissions; it’s that as faster-growing industrial economies, they will inevitably increase their energy use faster than developed economies. To date, globally, more energy use has always meant at least some increase in carbon dioxide pollution. In fact, China’s CO2 output trajectory, relative to the growth rate of its economy, has been roughly similar to that of the United States. India and the rest of the developing world have not done nearly as well.

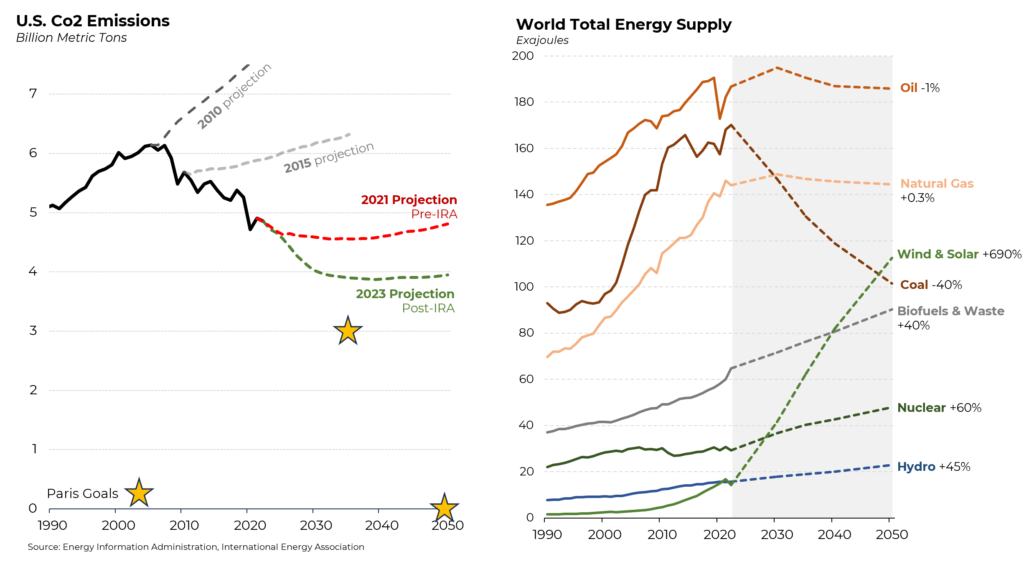

Happily, we are making some progress. Back in 2010, our emissions were projected to rise inexorably. But since then, thanks to the relatively new emphasis on addressing the problem and new technologies, they have dropped 15% from their 2005 peak. And each set of projections since then has been more optimistic. The most recent forecast showed a significant drop just from the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act. While that has brought our projected emissions in 2035 closer to the goals set out in the Paris Agreement, we are still, however, a very long way from meeting the goal of zero emissions by 2050.

That’s because the world continues to depend heavily on fossil fuels. While use of renewables – like wind and solar – has grown quickly, they still represent only a small part of the world’s energy supply. Oil, coal and natural gas continue to dominate. Indeed, the biggest part of the improvement in CO2 emissions has come not from renewables but from substituting natural gas, a cleaner-burning fuel, for coal. Even if current ambitious projections for more renewables and less coal are met, we would still see 2.4 degrees Celsius of warming by 2100, above the 1.5-degree Paris Accord goals.