Congress narrowly avoided another government shutdown on Thursday – but did so by kicking the can down the road, leaving key issues of government spending and immigration policy to be dealt with over the next six weeks. Unusually, while the Senate is more often the dysfunctional body of Congress, it’s the House of Representatives that has become the stumbling block in making progress on the important issues facing the country.

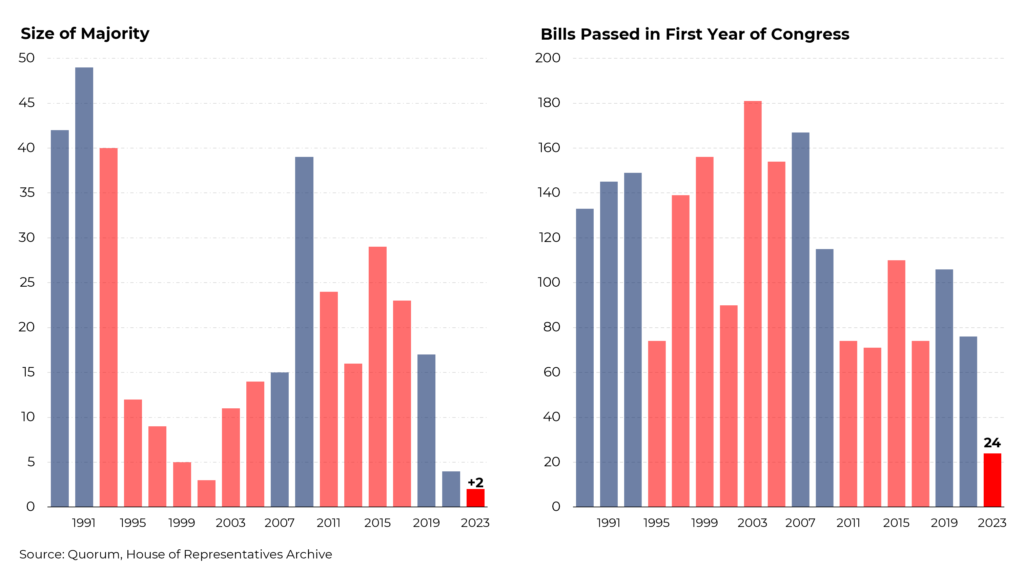

Part of the House’s problem is that the Republicans have the smallest majority of any party in recent history. Though they began the Congress with a four-seat majority, that has now shrunk to two seats as a result of the resignations of George Santos and former Speaker Kevin McCarthy. While McCarthy’s currently vacant seat may be filled by another Republican, Democrat Tom Suozzi is likely to defeat Republican Mazi Pilip to take over Santos’s seat. Bad weather and illnesses among its members have also made mustering a majority challenging for the Republicans.

But the House has been able to function in the past (notably in 2001-2) with almost as slim a margin as at present. This time around, however, the House has passed just 24 bills in the first year of its two year term, down from 75 over a the same period in the previous Congress. Why? Largely because of the presence of the far right Freedom Caucus, which brought down former Speaker Kevin McCarthy after just 269 days in office.

When Republicans took over the House in 2023, they pledged to observe “regular order,” including passing budgets in advance of the Oct. 1 start of the government’s fiscal year. Nonetheless, the government still doesn’t have a budget for the current fiscal year and will continue operating on an interim basis until at least March 1. Even with another six weeks or so of breathing room, finding common ground just within the Republican caucus will prove challenging.

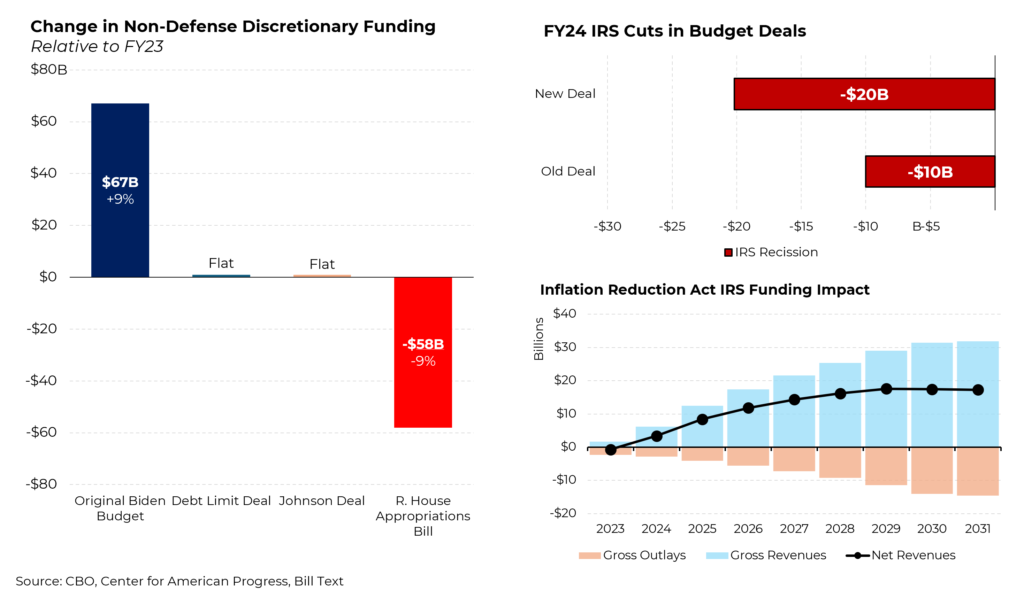

While Mike Johnson, the new Speaker, reached a handshake agreement with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer on a package similar to the one that McCarthy had agreed to, conservative Republicans have been demanding $58 billion of cuts from the agreed upon $773 billion of domestic discretionary spending, the same amount as was spent in the last fiscal year.

But there was one important difference in the Johnson-Schumer deal from the McCarthy agreement: another $10 billion cut in funding from the Internal Revenue Service, on top of $10 billion to be cut this year under the McCarthy agreement. (Recall that IRS funding was increased in 2022 by $80 billion over 10 years.) This cut is not about saving the government money; adding IRS funding increases the government’s tax collections and reduces the deficit by more than the cost of the extra spending.

Then there’s immigration policy, riven by a mix of politics and (again) extreme demands by the Republican right wing. While Senate Republicans have made clear that they believe they will get a better deal at present then they will if they retake the White House in November, House Republicans believe that doing nothing will hurt President Biden’s chances in November and in any event, the right wing (again) wants far more draconian changes than the Senate will agree to.

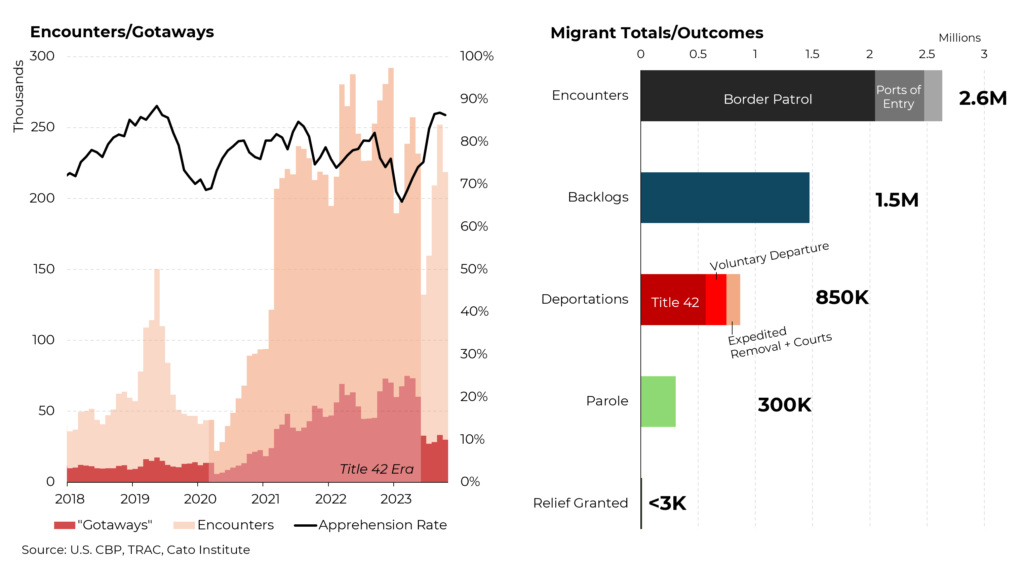

Let’s be sure we understand the facts about the crisis at the border. Yes, the surge in the number of “encounters” has gone up significantly, for a variety of reasons. But those encounters could also be called “apprehensions” – all 2.6 million of them ended up in the hands of Customs and Border Patrols. The number of “gotaways” – migrants who succeed in crossing the border and becoming illegal immigrants, has actually been falling and represents only about 15% of the total number of attempted crossings.

What happened to the 2.6 million? 1.5 million are working their way through badly backlogged courts where they can apply for asylum. Another 850,000 left the country, either voluntarily or involuntarily. 300,000 came from strife-riven countries like Haiti or Venezuela and remain in the country on temporary legal “parole” programs. Fewer than 4,000 have been granted asylum thus far.