The surge of migrants at America’s southern border looms large as a 2024 election issue. But the debate about our immigration policies and what is actually happening is filled with confusion and misinformation. A look at the data shows a reality considerably different from common perception; we are suffering from a complicated, overburdened system that serves neither Americans nor migrants well.

Anti-immigration forces would have us believe that millions of would-be Americans are sneaking across the border every year. That is hardly the case.

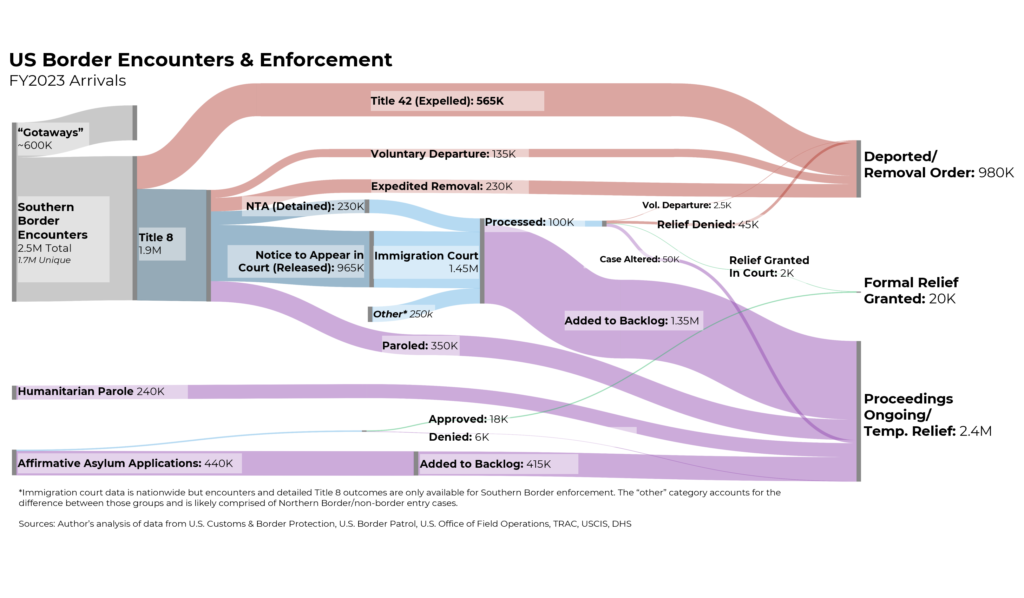

In the 12 months ending Sept. 30, only a minority – estimated at about 600,000 and known as “gotaways” – evaded border controls and melted into American communities. A far larger number (2.5 million) “encountered” U.S. Customs and Border Protection. The bulk (about 2.1 million) were apprehended along the border while trying to sneak in. But a significant number, some 400,000, were asylum seekers who voluntarily presented themselves to border officials at ports of entry and followed established procedures.

What happened to the “encountered” individuals?

Until this May, many (565,000) were immediately expelled under Title 42, a provision implemented by the Trump administration during the COVID-19 public emergency that allowed the government to remove migrants without trials.

The rest were treated under “Title 8.” Of the 1.9 million encounters in this category, some 365,000 migrants either voluntarily left the country or were placed into expedited removal, a procedure that, similar to Title 42, allows for deportations without formal proceedings based on the migrant’s risk profile or past record. The rest were given “notices to appear” in immigration court for deportation hearings (or a “parole,” which put them in a different legal category, usually based on their country of origin). The vast majority of those given court dates – comprising those seeking asylum and other forms of permission to remain in the U.S. – were simply added to the massive backlog of cases and remain in the U.S. awaiting trial.

Here’s how backlogged our immigration court system is: Of the 1.5 million court cases added this year, less than 50,000 were fully resolved, with 45,000 migrants ordered deported and relief granted to just 2,000. (Due to data limitations, some court cases counted are from non-southern border cases, like visa overstayers.)

All in all, of the 1.9 million migrants apprehended at the border through Title 8, some 1.5 million remain in the country with their removal cases ongoing.

Beyond the border but related to it, there is the “affirmative” asylum system run by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Migrants who enter through temporary visas or are otherwise not placed into deportation proceedings can apply for affirmative asylum. USCIS processed just 24,000 cases in the last year, compared to 440,000 added to their rolls.

In addition, beginning in February, some 240,000 Haitians, Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, and Cubans were granted “humanitarian parole,” allowing them to come to the United States for a temporary amount of time with the expectation that they will file for affirmative asylum or other relief while here. Border encounters for these nationalities plummeted in the months after this policy was created.

Here’s the scorecard for the 12 months ended Sept. 30: nearly 1 million deportations, 2.4 million migrants added to backlogs, and just 20,000 migrants granted relief.

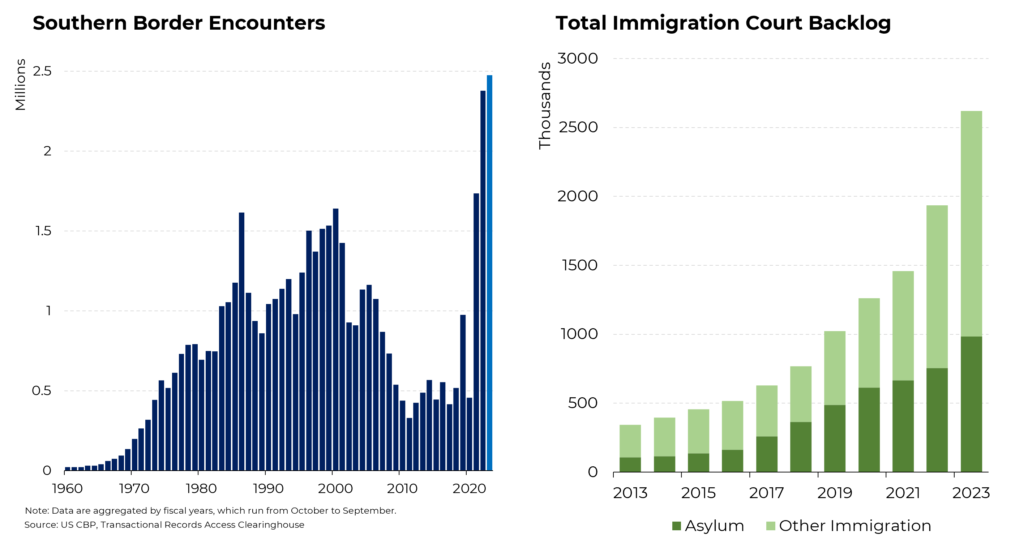

Encounters at the US border have spiked over the last three years for a number of reasons. Latin America saw a larger COVID-induced contraction than any region, and multiple countries—like Venezuela—have seen deteriorating political situations and escalating violence. Moreover, the hot post-pandemic U.S. labor market has encouraged millions of economic migrants to journey looking for work. Even as the Biden administration has dramatically tightened rules for asylum seekers, the influx of migrants has remained resilient.

This surge has overwhelmed our immigration adjudication system, which was overburdened even before the pandemic. There are 2.6 million cases currently in the immigration court backlogs, up from 350,000 a decade ago. Put another way: there are more than 4,000 pending cases per immigration judge. Trials often last years before decisions are made, leaving migrants in limbo in the United States.

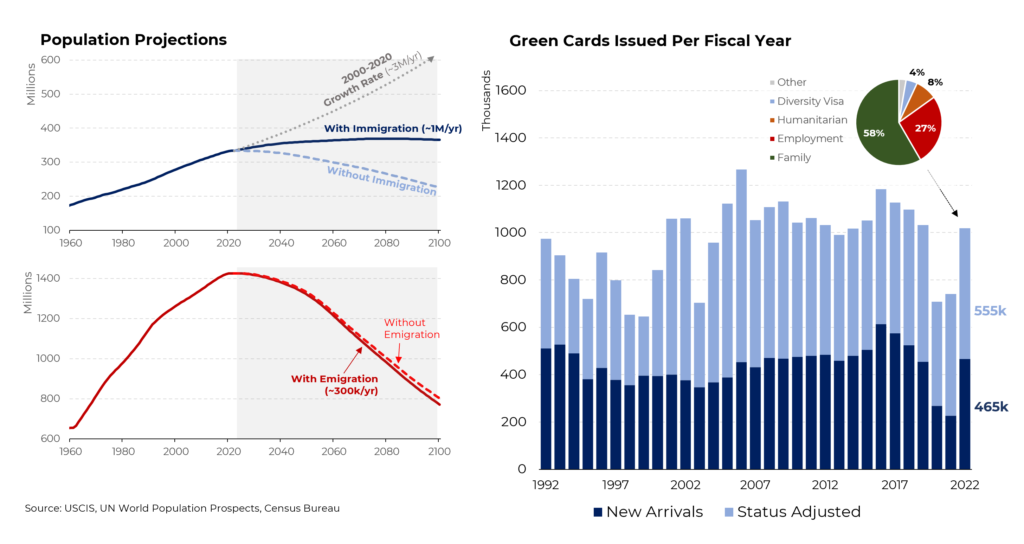

As our country ages and birthrates fall, migrants will prove indispensable to replenishing our greying workforce and growing number of retirees receiving benefits through Social Security and Medicare. The Census Bureau—assuming a normal tide of some one million migrants per year—estimates that America’s population, today just over 330 million, will grow at a tepid pace to a peak of 370 million in 2080. Without immigration, our population would start declining as soon as next year. To sustain our growth rate of 0.8% of the last two decades, we would need some 3 million migrants a year. By comparison, China—already shrinking and in demographic decline—sees net outflows of population due to emigration.

To take advantage of our position as the world’s top immigration destination, the U.S. can afford to greatly expand legal pathways to citizenship. The number of “Green Cards” given out annually hasn’t budged in thirty years, even as America’s population has grown by more than 30%. Most Green Cards go to family members of current citizens, with a third going to the especially important group of workers with special employment skills.