Thanks to Speaker Kevin McCarthy and House Democrats, a shutdown of the federal government was barely averted last weekend. Why is this happening so soon after Republicans and Democrats were supposed to have resolved their fiscal differences during the debt ceiling drama less than four months ago? The short answer: because the hard-right Republicans decided to ignore that agreement. That doesn’t augur well for what will happen after the 45-day Continuing Resolution (which temporarily maintains spending at last year’s levels) expires – or what will happen to McCarthy, whose head is now on the MAGA chopping block.

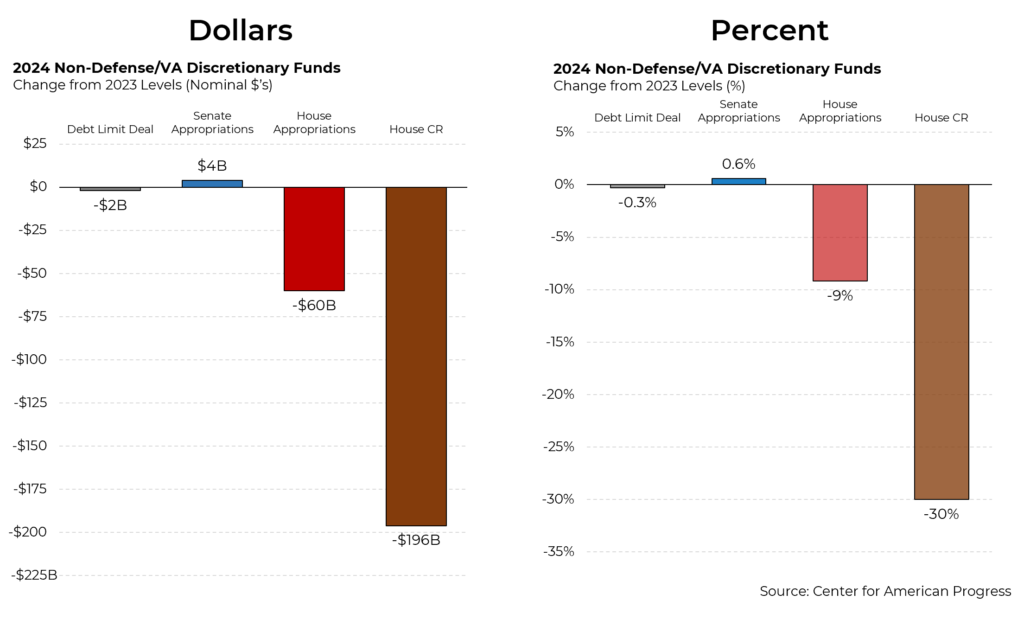

In the compromise that raised the nation’s debt limit, the two sides agreed to reduce non-defense/veterans discretionary spending for the fiscal year that began on Sunday by $2 billion (before adjusting for inflation). For their part, both Senate Democrats and Republicans have agreed on a spending package that would involve slightly more modest cuts than what was previously agreed to because of small increases in funding for agriculture, military construction, transportation, and housing.

On the House side, in an effort to appease the hardliners, Speaker Kevin McCarthy put forward a package that would slash spending by $60 billion. After that failed, he put forward a 30-day continuing resolution that would have cut spending by $196 billion. That was also killed by the extreme right wing Republicans.

In each of these packages, all the cuts would come from non-military (and non-veterans’) discretionary spending, meaning that this category of federal outlays would suffer a massive reduction: 9% under McCarthy’s first effort and an extraordinary 30% under his second proposal. Now, McCarthy has resolved to try and pass the 9% effort again, leaving the House essentially back where it started.

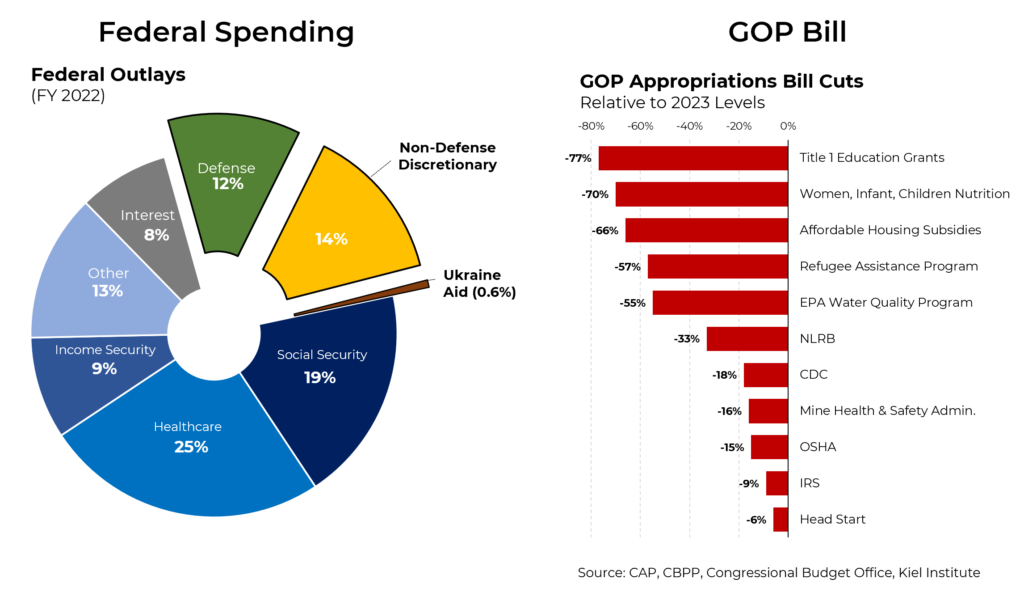

Why the massive cuts in non-defense discretionary spending? Because they are a relatively small portion of the budget: just 14% of overall spending, slightly more than the military. The other roughly 75% of government outlays go to so-called entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare as well as interest on the growing national debt. Part of the challenge facing budgeteers is that these mandatory programs have been growing substantially faster than the overall economy, as a result of factors like an aging society and rising interest bills. This will only become a bigger challenge in coming years.

Accordingly, the $60 billion set of proposed cuts would include massive reductions in everything from Title I education grants for low-income schools (77%) to water quality (55%) to the National Labor Relations Board (33%). It is an effort to dramatically reduce the scope and scale of government but cutting off its air supply (money). McCarthy did not provide much detail on his $196 billion package but obviously, it would involve even larger cuts in programs like these.

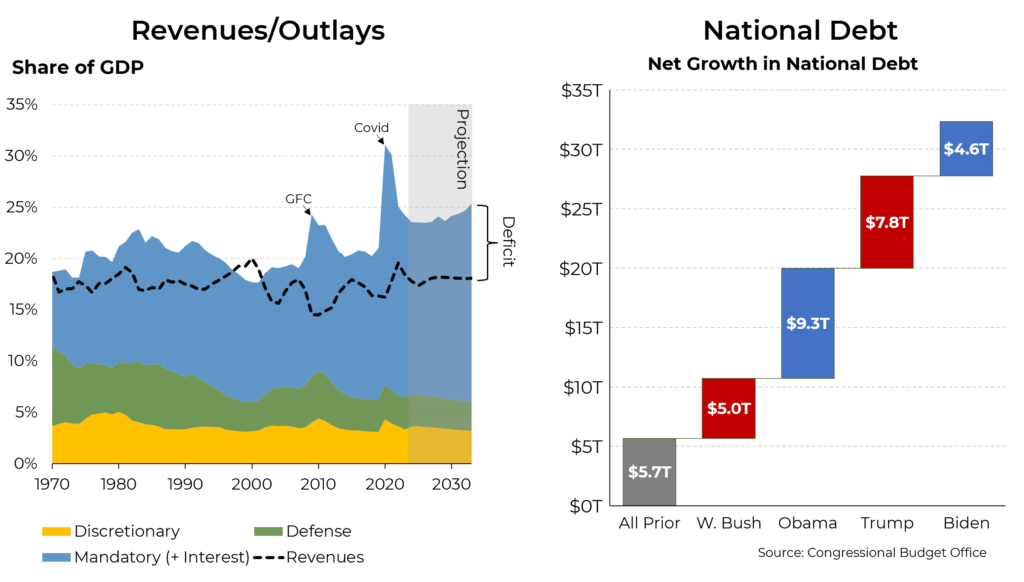

All of this also needs to be put in the context of rising deficit and debt levels. The deficit, which shot up during the pandemic before retreating modestly to $1.4 trillion, is projected to have risen to $2 trillion in the fiscal year that just ended. The burgeoning deficit is entirely a function of rising spending; tax revenues as a share of the economy have been roughly unchanged over the past 50 years. But with an aging society, demands for more robust social programs and a shared desire for a stronger military, it’s easy to argue that more tax revenues are needed. Note how tax revenues dropped following the Bush and Trump tax cuts.

Meanwhile, the national debt has already hit $33 trillion. Only $5.7 trillion of that total was incurred in the first 224 years of the nation’s existence. Donald Trump alone added $7.8 trillion in just four years, almost a quarter of the total.

That said, shutting down the government is not the way to solve this problem. Note that every government shutdown of the last 30 years has occurred with Republicans in charge of the House of Representatives and the 2018 shutdown (the longest in history) didn’t end until the Democrats took back the House.