It’s rare to see a change in government policy produce a quick response in the private sector, but that’s what’s happening with the Inflation Reduction Act and, more specifically, with its provisions to spur a transition to cleaner energy in order to minimize the warming of the planet. Nonetheless, Republicans are still trying to limit its effectiveness.

Advocates of a transition to cleaner energy have mostly found their hopes unmet by the desultory pace at which the move to renewable energy generation, electric vehicles, and the like should be heartened by what has begun to transpire.

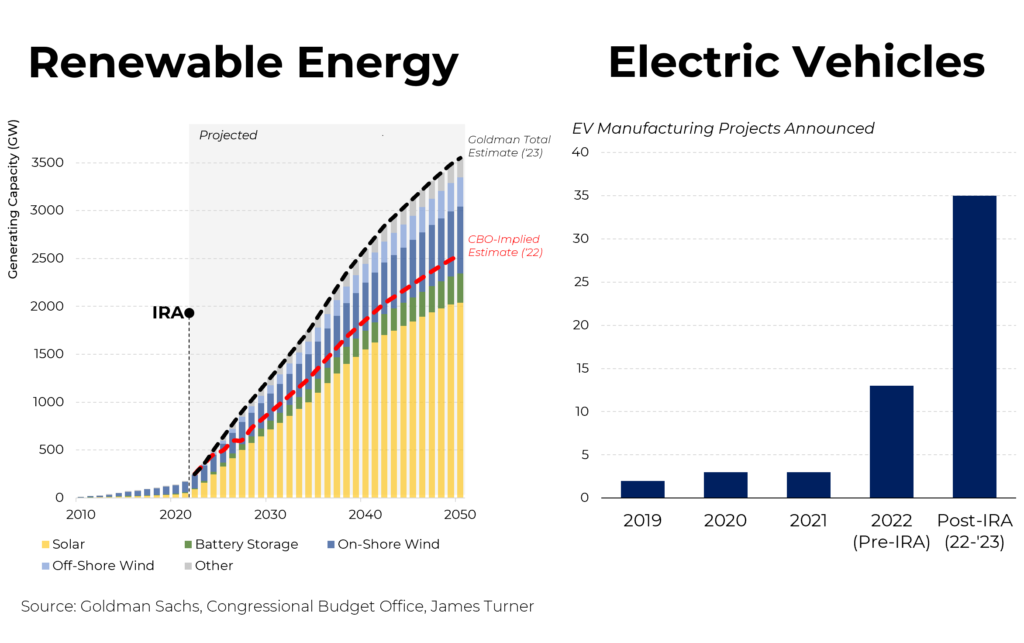

Today, the United States has roughly 1,100 gigawatts of energy generating capacity, with renewable sources comprising just under a quarter of the total. In 2021, the US added a total of 22 gigawatts of generating capacity to the grid, 80% of which was renewable. By comparison, this year, the US is expected to add more than double that: 55 gigawatts of capacity, nearly 90% of which will be renewable.

Goldman Sachs estimates that total renewable generating capacity will grow to roughly 3,500 gigawatts by 2050, from 250 gigawatts today. Most of this new capacity will come in the form of solar, although battery storage and wind are also expected to play significant roles. Putting it another way, in the eight months since the passage of the IRA, 330 utility-scale renewable projects have been announced, compared to 160 in the eight months prior to the passage of the IRA.

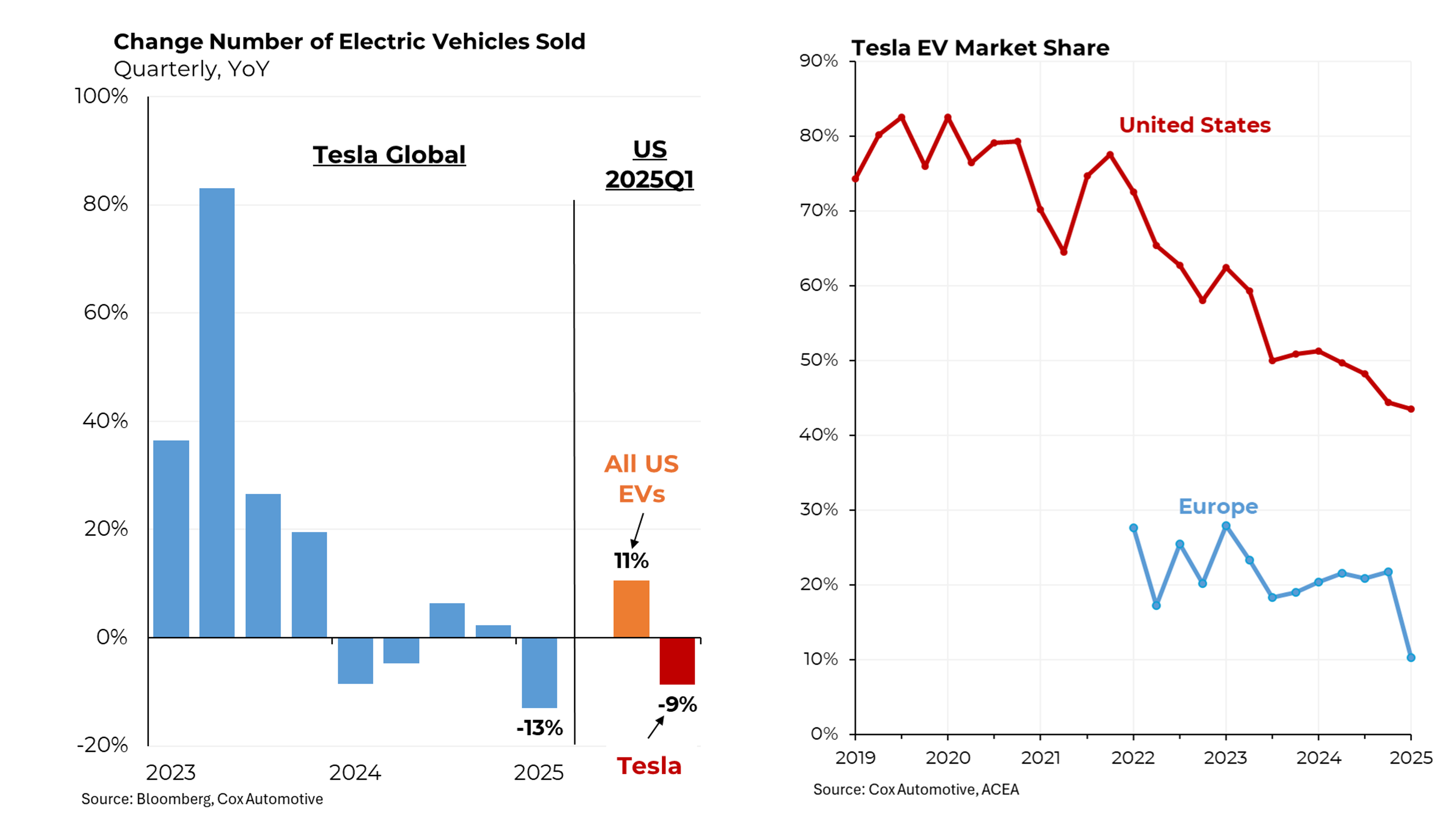

A similar phenomenon is occurring with electric vehicles. A total of 35 new EV manufacturing projects (mostly factories and lithium plants) have been announced since August of last year, more than double the same length of time since passage of the IRA.

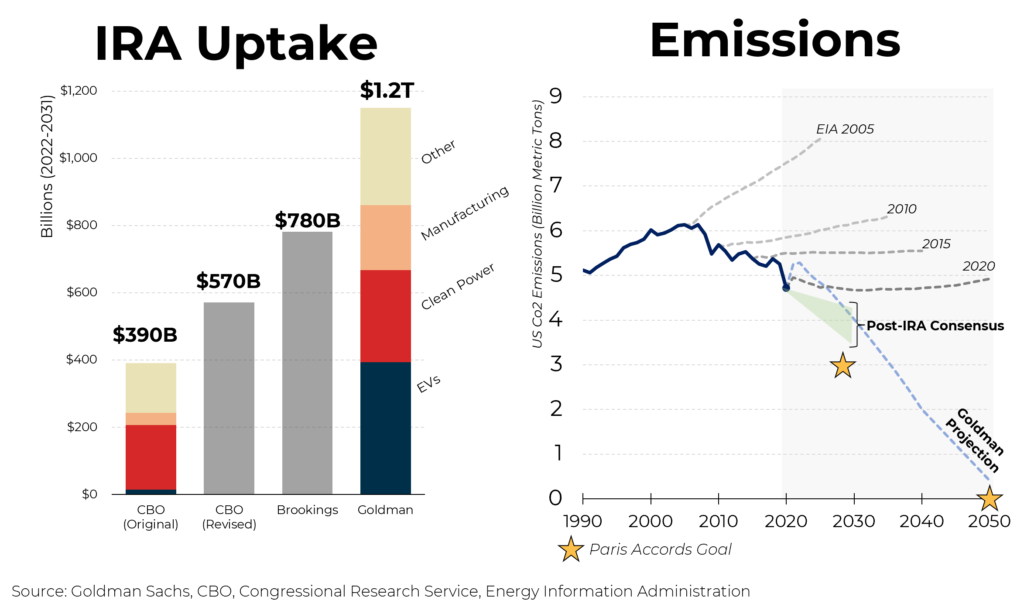

Why such an upsurge? In large part because of the tax credits and other financial assistance in the IRA. We have seen many projects that were not economically viable become viable. That comes at a cost. When the CBO originally scored the IRA, the agency projected that it would cost the government $390 billion over the first 10 years. More recently, the CBO raised its estimate to $570 billion. Other forecasters expect substantially higher cost, with Goldman Sachs projecting that the bill could reach $1.2 trillion. Unlike most other cost overruns, this is largely good news!

In return for this large expenditure, estimates of carbon dioxide emissions in the United States have been coming down. As recently as 2020, the Energy Information Administration (part of the Department of Energy) projected that our emissions would level off at roughly the current level. Since the passage of the IRA, the consensus is now for significantly lower emissions. Goldman Sachs believes that by 2050, our CO2 emissions could be close to zero.

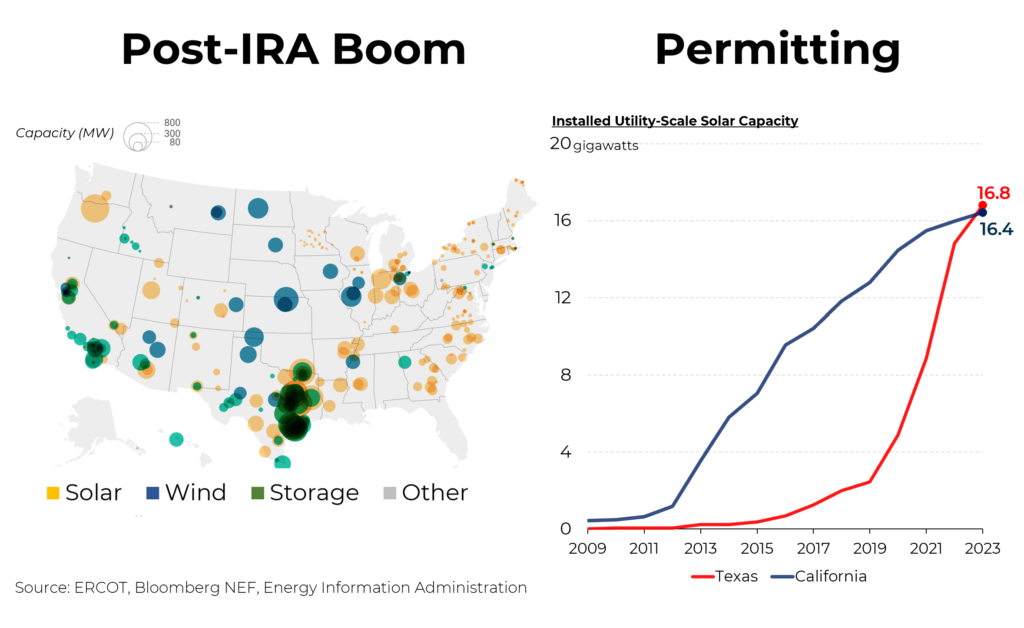

Interestingly, the biggest impediment to even more development of renewable energy facilities is the problem of permitting. In the race to add these projects, historically laissez-faire Texas stands far in the lead, with 79 new projects announced in the last eight months. While California is second in new projects, Texas’s strong recent showing means that they now have more solar generating capacity than California. (As a result, the fossil-fuel friendly Texas legislature is now considering bills that would slow permitting for renewables.)

Permitting obstacles also exist on the national level, with average environmental reviews now taking 4 1/2 years on average (up from three years in the 1990s). It can also take up to five years to get a completed project connected to the grid. Among the Republican wish list in the current debt ceiling deliberations has been changes to expedite permitting of all kinds of facilities, something that West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin has also been pushing.