On MSNBC’s Morning Joe today, Steven Rattner explained the key drivers behind repeated record highs in the stock market; a strong economy is not one of them.

While the number of Americans infected by the coronavirus passed 6 million last month, the stock market notched its best August in 34 years. That leaves the closely watched Standard & Poor’s index of 500 stocks in record territory, up nearly 10% this year (including dividends), a fact that President Trump regularly points to as a barometer of his success as president.

What gives? Why has an economy that has experienced the biggest collapse since the Great Depression not — at least to date — inflicted any lasting damage on a market that is often expected to reflect the state of the economy or, at least, of corporate profits?

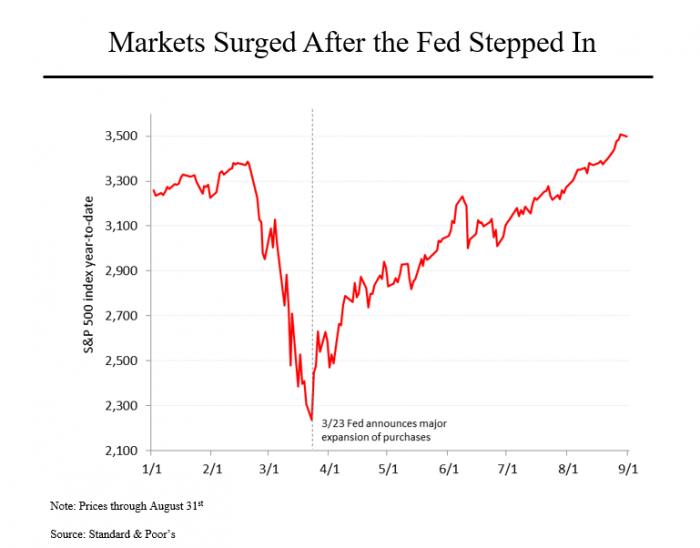

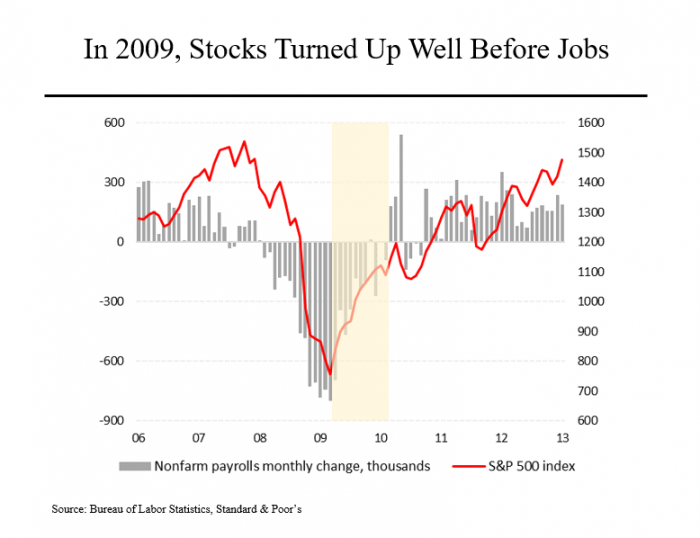

Some hold the view that the economy’s troubles will be short-lived; a V-shaped recovery will soon unfold and the stock market is merely looking ahead. As this chart shows, that’s in essence what happened in 2009; the market turned up just as job losses were at their worst. And if the market doesn’t reverse, that will be what happened this time around; stocks bottomed on March 23 while job losses peaked in April.

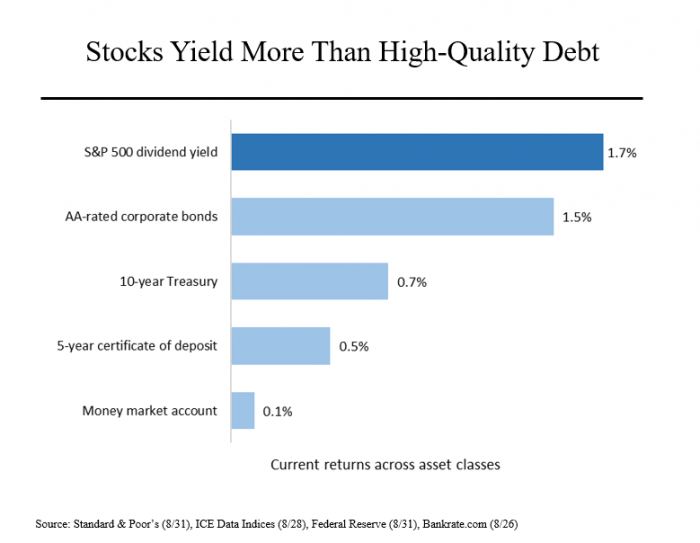

But I believe that the most significant driver of stock prices is the huge amount of liquidity that the Federal Reserve has injected into the financial system, in an effort to counteract the depressive economic impact of the virus. That has pushed interest rates to record lows, turning money market funds, bonds and other fixed-income instruments into low-returning investments. The S&P stocks, for example, currently have an average dividend yield of 1.7%, compared to 0.7% for 10-year Treasury notes. So an investor can now make more in current income from stocks than from high-quality fixed-income securities while participating in any future appreciation in share prices. (Yes, while stocks can also go down, over the long term, they have always appreciated.)

Coincidence or not, the day the Fed announced a massive injection of liquidity, the plunge in the market abated and the extraordinary recovery in stocks began. Since then, the Fed has reiterated its commitment to low rates multiple times, including as recently as last week.

In fairness, the Fed is not the only factor influencing the market. Individual investors, known for their often poor timing of entry and exit points, have been trading actively, aided by commissions that major online brokers have dropped to zero.

And the overall strong performance of stocks masks the fact that the market has recognized that profits of fast-growing technology companies have not been hurt by the pandemic while more cyclical companies in manufacturing, travel, hospitality and the like are suffering mightily. Since the market peaked on Feb. 19, the tech-heavy Nasdaq index is up 20% while the Dow Jones average — more oriented toward cyclical companies — remains lower by 3%.

So at the moment, as much as President Trump would like to think otherwise, lofty stock prices are not a sign of a strong economy. And in the long run, the view of professional investors that share prices must eventually align with economic fundamentals will prevail.

To me, those fundamentals look scary.