On MSNBC’s Morning Joe today, Steven Rattner presented charts showing the accelerating toll that Trump’s trade war has taken on US exporters, consumers, and the stock market.

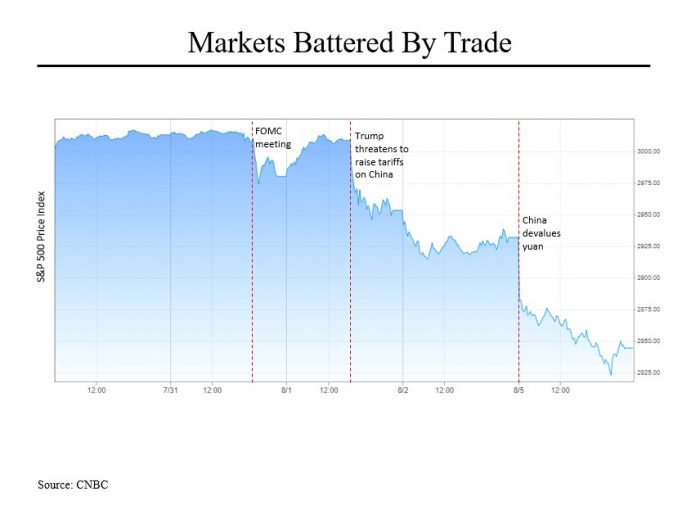

The stock market cratered Monday; major indices plunged by 3% and more than $700 billion of value was lost. Full credit for that debacle goes to President Trump for the disastrous trade war that he began almost upon taking office. For months, the market has mostly shrugged off the relatively small rounds of tariffs but the last several days of escalating measures by both the United States and China proved too much.

In a sense, the first noteworthy of the recent events was the decision by the Federal Reserve last Wednesday to cut interest rates by 0.25%. The need for that reduction was itself arguably a consequence of a slowing economy caused by Mr. Trump’s earlier rounds of tariff increases. Tariffs function much like taxes; as they increase, economic activity decreases, particularly in goods that are traded globally. But the market was unhappy that the Fed’s commentary around the cut did not hold out enough hope about more rate reductions in coming months.

No sooner had the market recovered from that disappointment when, on Thursday, Mr. Trump announced that he planned to impose tariffs on another $300 billion of Chinese goods on September 1. Still worse news came on Sunday when China, rather than seeking an accommodation with the Trump administration, surprisingly devalued its currency, leading to Monday’s debacle.

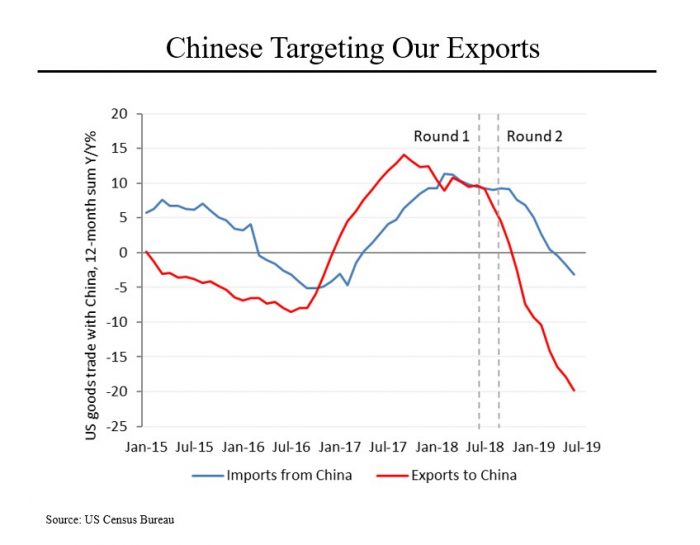

Perhaps the stock market is right to be so concerned; the results of the early rounds of tariffs and countermeasures have been worrisome – at least as much for the United States as for China. Since Mr. Trump began imposing tariffs over a year ago, American exports to China (principally soybeans and cars) have fallen by 20% from their peak a year ago. That’s in part because China, which exercises significant state control over its economy, can simply decide to stop buying goods like soybeans. Meanwhile, American companies have continued to bring in Chinese goods; those imports have only dropped by 6% (from their peak last October).

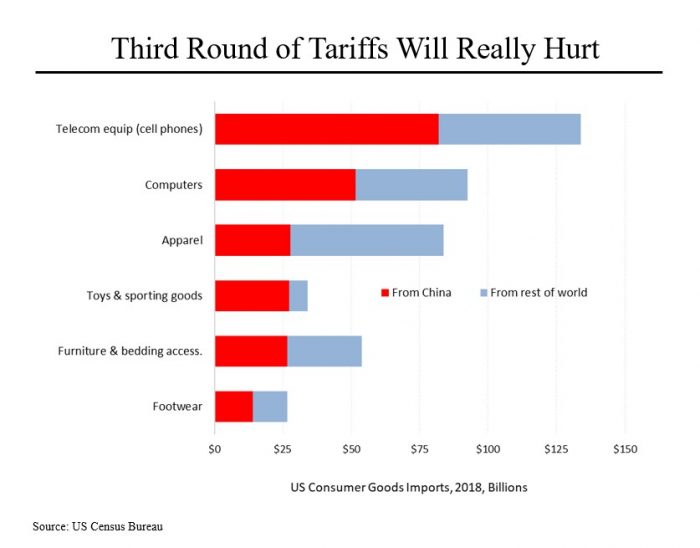

But without a change in course, the new tariffs will take a bigger bite out of American consumers because the earlier rounds of levies focused on goods bought by businesses; the next round will hit consumer items. The fact is that many popular products – from cell phones to shoes – are simply not made in America in significant quantity anymore. And the biggest provider of most of these imports is China. For example, nearly 90% of all toys sold in America are made in China.

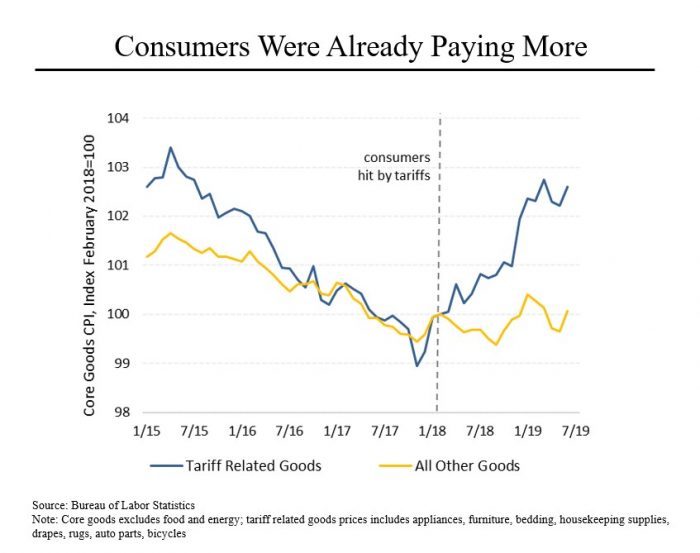

Even the earlier rounds of tariffs have had an appreciable effect on the prices that consumers pay. As this chart shows, prices for all “core goods” (think manufactured items) had been declining, in large part because a strong dollar made imports less expensive. But since early last year, when the first tariffs were imposed on washing machines and solar panels, prices of goods subject to the tariffs have been rising while prices of those not subject to tariffs have remained largely unchanged. (Remember that taxing products from a low cost country like China has the effect of allowing providers of those products in other countries to raise their prices.) All told, many economists believe that when the full set of tariffs take effect, the cost to a typical American consumer will be greater than the benefit received from the Trump tax cut.