Originally published in the New York Times

For months, the question in many minds has been not whether Detroit would file for bankruptcy, but when.

But while Detroit’s decision this week to enter bankruptcy might make it easier to improve the city’s fiscal position, it will prove far tougher to design and implement an effective restructuring for Detroit than it was to put General Motors and Chrysler through Chapter 11.

That’s partly because municipal defaults are handled under a different section of the law — Chapter 9 instead of Chapter 11. The latter, which governs companies, includes a provision that allowed General Motors, the city’s largest company, to take a quick, 39-day rinse in bankruptcy.

Cities must go the slow route, almost certainly at least a year in Detroit’s case. Such lengthy bankruptcies are costly, not just in fees but more so in distraction for city officials and uncertainty for local businesspeople.

More important, Detroit is in far worse shape than the auto companies were in 2009. Its steadily declining population has meant falling tax revenues and, because it is difficult to cut expenses as quickly as revenues slip, six consecutive years of deficits.

And unlike the auto companies, which could close unneeded plants and shed workers without diminishing their ability to produce quality cars, Detroit has been cutting for years and is already delivering substandard services.

Average police response times have reached 58 minutes, compared with a national average of 11 minutes. Its per capita violent crime rate is nearly triple that of Cleveland and St. Louis, and it has fewer than half as many functioning streetlights per square mile as those cities. And on and on.

But while Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder has capably overseen Detroit’s march to Chapter 9, neither the state nor the federal government has evinced any inclination to provide meaningful financial assistance.

That’s a mistake. No one likes bailouts or the prospect of rewarding Detroit’s historic fiscal mismanagement. But apart from voting in elections, the 700,000 remaining residents of the Motor City are no more responsible for Detroit’s problems than were the victims of Hurricane Sandy for theirs, and eventually Congress decided to help them.

America is just as much about aiding those less fortunate as it is about personal responsibility. Government does this in so many ways; why shouldn’t it help Detroit rebuild itself?

Many call for scaling back the city to fit realistic population projections. While logical, the potential for downsizing Detroit is limited because the city’s population didn’t flee from just one neighborhood; the departures were scattered, requiring Detroit to deliver services across a geographic area the size of Philadelphia, with less than half the population. Further cuts will surely come, but in some key areas, like public safety and blight removal, Detroit needs to spend more, not less.

That necessitates large-scale reductions in its liabilities, which total as much as $18 billion. By comparison, the country’s second largest municipal bankruptcy — that of Jefferson County, Ala., which is slightly smaller than Detroit in population — involves $4 billion of liabilities.

Detroit faces greater challenges than the automakers because the structure of its obligations is quite different from those of General Motors and Chrysler.

Detroit owes approximately $5.3 billion on debt that has first call on all water and sewer revenues, which means the holders of that debt have to the right to take as much of the water and sewer fees (after operating expenses) as are needed to service the debt.

The bulk of its obligations are to the grossly underfunded pension plans and for retiree health care costs — nearly half of the city’s total liabilities. The city has suggested that it cut these by 90 percent. Although retirees don’t have a lot of legal rights in the bankruptcy process, it is difficult to imagine — on either a human or a political level — an exit from bankruptcy that would include reductions of this magnitude.

The first duty to help lies with the state: Gov. Rick Snyder has made clear that Detroit’s success is key to Michigan’s success.

For starters, if the state assumes responsibility for the $1.25 billion in reinvestment spending that Detroit’s emergency manager, Kevyn Orr, has included in his proposed budget, the city could use those freed-up funds to trim the potential pension reductions of retirees. And the Obama administration should comb through its urban programs to try to allocate more funds to a city that is truly in distress. (If I thought it could pass Congress, I’d happily support a special appropriation, but the politics of any spending are toxic in Washington these days.)

Given the depth of Detroit’s hole, no one should doubt that one of the important principles of the auto rescue — shared sacrifice by creditors, workers and other stakeholders — should be maintained.

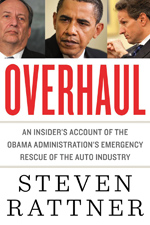

When President Obama rescued the auto companies, his decision was politically unpopular. By the time of last fall’s presidential election, a majority of Americans had swung in favor of the move. History could repeat itself.