Originally appeared in The New York Times.

TOO often the debate over how to restart Europe’s economy veers into the conveniently crisp alternatives of stimulus versus austerity. Should the pressure to reduce government deficits be relaxed? Should central bank actions to lower interest rates have come sooner and been more aggressive?

That simplistic debate has returned to the forefront, with the European Central Bank’s plunge into purchasing the sovereign debt of its member nations and Greece’s resounding vote at the ballot box against spending cuts.

But the focus on macroeconomic policy underappreciates the critical importance of smaller structural problems that collectively amount to a bigger challenge for Europe.

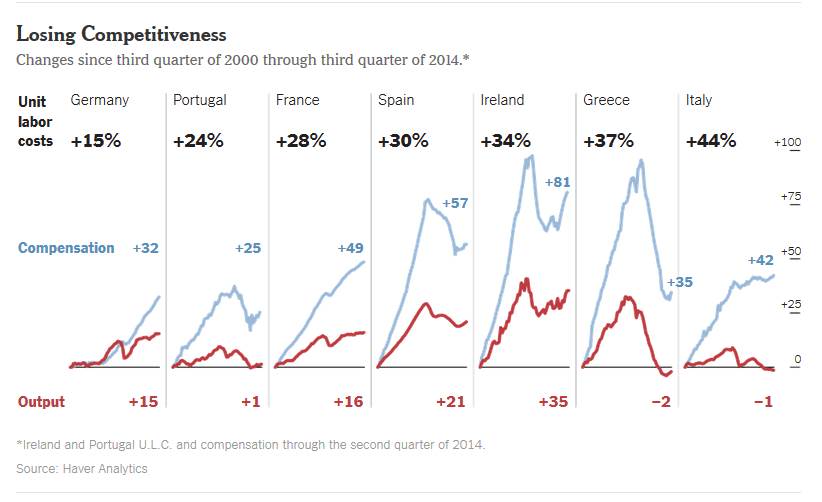

Archaic restrictions on hiring and firing workers, flawed energy policies and kilometers of red tape that can make even starting a business difficult — just to name a few — have combined to damage the Continent’s ability to compete in increasingly global markets.

Among major countries, France and Italy have these problems most acutely, with wages continuing to rise even as the efficiency of workers has stagnated.

In France, President François Hollande arrived in office in 2012 atop a leftist wave and responded with policies that ranged from lowering the retirement age to 60 to raising corporate and value-added taxes.

His policies have even managed to get French businessmen into the street, shouting “enough is enough” into megaphones — an expression of their frustration with the layers of regulations, such as a new requirement that all part-time jobs be at least 24 hours per week. Unpopular and under pressure from the European Union, Mr. Hollande has tacked modestly toward the center.

Meanwhile, Italy’s youthful new prime minister, Matteo Renzi, arrived determined to reverse three years of recession by overhauling problems such as rigid labor laws and a grindingly slow judicial system.

After months of battling, he recently made progress on a bank reform bill and secured initial passage of his jobs act. That occasioned demonstrations and strikes across the country by workers who feared that it would succeed in dismantling Italy’s 2,700 pages of labor market regulations, which effectively institutionalized inefficiency by making it exceptionally difficult to fire workers.

Even generally sensible Germany has veered wildly off course in its energy policy. In the wake of the 2011 nuclear disaster at Fukushima in Japan, the country, which derived about a quarter of its energy from low-cost nuclear power, has begun shutting down its reactors. That came on top of a requirement that utilities purchase specified amounts of clean power at prices far higher than electricity from conventional sources.

A result is weakened competitiveness for Germany’s much-vaunted industrial sector and suggestions by businessmen that new facilities requiring large amounts of power may be located in more hospitable countries.

More positively, Spain, while still plagued by an unemployment rate of 23.7 percent, has managed to implement labor and tax reforms, helping the country to begin adding jobs again amid renewed economic growth.

With all the problems facing Europe, the recent European Central Bank decision to buy bonds amounts to reaching into a medicine cabinet when the patient needs open-heart surgery.

For one thing, high interest rates are hardly Europe’s problem. France can borrow at 0.6 percent for 10 years, and even Spain and debt-laden Italy can borrow at around 1.5 percent.

And despite robust European Central Bank financing programs, loan demand from the private sector remains weak. Since 2008, business investment has dropped about 15 percent.

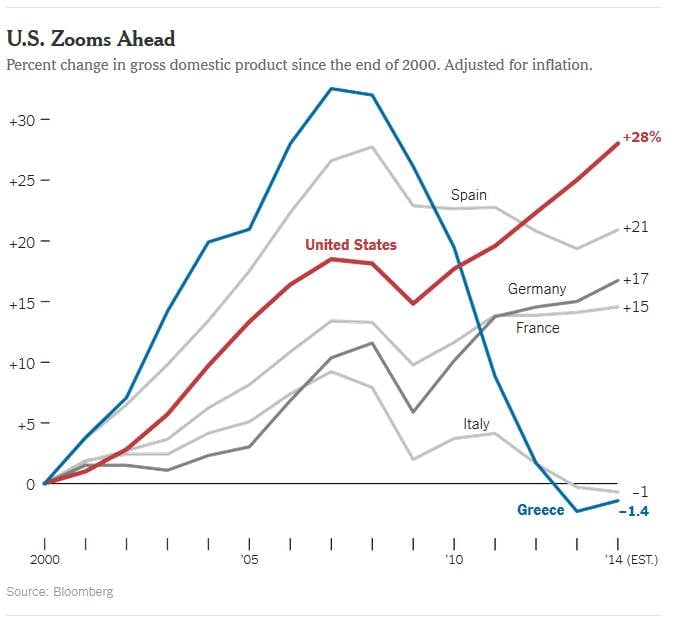

Many explanations are offered for why the eurozone is lagging. Some say it’s lack of immigration. Sure, the United States has benefited enormously from the diversity and productivity of newcomers. But with 11.5 percent unemployment, the eurozone wouldn’t seem to need more workers.

Income inequality? Unlike the United States, where inequality has soared, on the Continent, the gap between the haves and the have-nots, although large, has widened only modestly.

To be sure, in the appropriate context, more public spending and investment and commendable efforts to avoid deflation, like those of the European Central Bank, would be well advised.

But under the present circumstances, such steps risk distracting the Continent even further from addressing its most serious challenges.

Europe needs to become more competitive in global markets. That can be achieved only by a variety of policy changes, such as keeping top tax rates at sensible levels and regulatory reforms that would give companies more freedom to manage their businesses as they see fit, including, when necessary, closing plants and reducing head counts. That is the only viable path to sustainable growth and, ultimately, more jobs.